Will the Labour Code Bills Take Us Back to the 19th Century?

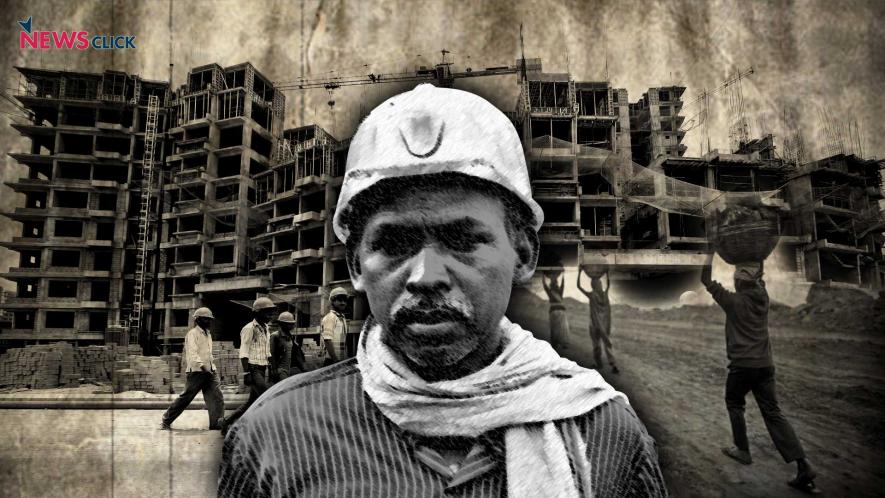

File Photo.

The labour code bills, if passed, will herald an employment arrangement in the country which can be traced back most closely to industries in 19th century Europe. Experts say they were characterised by a deep absence of trade unions, restrictive bargaining powers of workers and extreme unilateral power of employers to hire and fire.

The government has also said that it held tripartite consultations prior to introducing the three bills, a claim which was called “fraudulent” by Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) general secretary Tapan Sen. “All that was proposed by the unions were rejected, while everything that was proposed by the representatives of employers was accepted,” he said.

That said, the three codes – which will replace and subsume 25 central labour enactments – were deplored by the labour union leaders for being, among other things, the “most draconian changes to labour laws”, enabling the government to “evade its constitutional obligations.”

The three bills – The Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (OSH&WC) Code, 2020, The Industrial Relations (IR) Code, 2020, and The Code on Social Security, 2020 – were tabled in Parliament on Saturday. Last year, The Code on Wages, 2019, which sought to regulate wage and bonus payments in all matters employment, was passed by both houses of Parliament.

Altogether, the four codes form part of an ambitious move by the Narendra Modi government to bring in reforms for the easier compliance of labour standards, thereby bolstering investments.

For the working population, however, the changes hold a “grim future”, said K.R. Shyam Sundar, professor of labour studies at XLRI Jamshedpur. “It is unfortunate that the central government sought to effect extremely unhelpful provisions at a time when the country is ridden with a pandemic and unemployment rates are alarmingly high,” he told NewsClick.

‘Workers are Being Stripped of Their Hard-Fought Protection’

The OSH&WC Code Bill, which consolidates 13 labour laws, seeks to regulate health and working conditions in factories, mines, and in docks, among others. Under the proposed law, labour regulations have been extended to cover migrant workers – all those who earn up to Rs 18,000 and migrate from one state to another. Even then, academics call it “a major opportunity missed” to ensure universal safety and health coverage to all economic activities and types of workers.

Firstly, the proposed law will only be applicable to establishments with at least ten workers, thereby excluding smaller units. Further, the bill seeks to increase the threshold of application of key provisions of current legislations to establishments.

The definition of factories, which will have to adhere to safety standards, has been amended to include only those units which use power to run and employ more than 20 employees, and those which are without power and employ more than 40 employees. Currently, under the Factories Act, 1948, the limits are 10 and 20, respectively.

Similarly, contract labour regulations, which currently apply to companies employing at least 20 contract workers, have been changed under the proposed law to cover only those that hire at least 50 workers.

It will mean that close to two-third of working factories will fall out of the contract labour regulations, according to Sundar. “In a civilised country, the ambit of labour laws must be widened. However, given the neo-liberal form of globalisation that has been witnessed in India, a reverse is taking place,” Sundar said. “The workers are being stripped of their hard-fought protections – earned through decades of struggle,” he rued.

Sundar added that this was nothing but a “nationalisation” of regional labour amendments, brought about earlier by state governments. For instance, states such as Uttarakhand and Punjab recently gave their nod to ordinances which brought in similar relaxations.

Similar attempts were pointed out by other experts who spoke of the IR Code Bill. The proposed code, which deals with contentious issues of industrial disputes and terms of employment contracts, has eased retrenchment norms – allowing factories with up to 300 workers – as opposed to 100 at the moment – to retrench, lay off or shut down without its nod. States like Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Gujarat have already put these measures into place.

In a bid to end strikes, the IR Bill proposes the requirement of prior notice to all industries. The provision is currently only applicable to public utility services under the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947.

Labour law expert Saurabh Bhattacharjee, who teaches at the National University of Juridical Sciences in Kolkata, fears that this would lead to “labour unrest”, which will invite “greater repression”.

“The nature of the state is changing to embrace a more authoritarian form of governance. Its ramifications can also be seen in the changing labour laws, which are only to ‘facilitate’ business and have nothing for the protection of workers,” he said.

The Centre has also proposed to do away with the requirement of framing standing orders for the workforce in companies that employ up to 300 workers, even though its application has been increased to cover every industrial establishment through the IR Code Bill.

A standing order is a legally binding document that constitute terms and conditions of service that currently apply to establishments having 100 or more workmen.

The changes proposed are in addition to the consolidation of existing legislations on social security and protections of the Indian workforce, effected by the Code on Social Security Bill. The code is being hailed for extending the security net to cover app-based workers, more commonly employed by gig companies like Uber, Ola, Swiggy and Zomato among others.

The Bill proposes a social security fund for such workers, in which the companies will soon have to contribute not “more than five per cent of the amount paid to gig workers.” A National Social Security Board is proposed to be set up for the same purpose.

Shaikh Salauddin, national secretary, Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT), welcomed the proposal. He, however, contended that “much more than mere social security is needed for the app-based workers, as they continue remain in legal grey zone.” Often treated as independent partners, these workers find no place under the country’s labour regulations.

The said code also fails to emphasise social security as a right, according to the Working Peoples’ Charter, a coming together of organisations working in the informal sector. “In addition, it does not stipulate a clear date for enforcement, which will leave millions of the working poor out of its protections,” a briefing note prepared by it, said.

Anamitra Roychoudhary, professor at Centre for Informal Sector & Labour Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, expressed his concerns over the dilution of the tripartite composition of Employee State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) by the proposed social security code. “The government may further carry the dilution process in a step-by-step manner, the overall implication for which is bound to be felt by the existing social security schemes,” he said.

CTU Leaders Question Sanctity of Tripartite Consultations

While introducing the three bills, Labour and Employment Minister Santosh Kumar Gangwar reportedly told the Parliament that the bills had been drafted after following pre-legislative consultative policy including tripartite consultations, regional conferences among others. This claim, however, hasn’t found support among representatives of the central trade unions.

Amarjeet Kaur, general secretary, All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC) told NewsClick that tripartite consultations were held at “regional levels”, as opposed to the tradition of holding them with national leaders of trade unions. “Our union’s representatives, with clear knowledge of issues pertaining to labour laws were not even able to participate in those meetings,” she said, questioning the sanctity of such consultations.

A day after the three bills were introduced in the Parliament, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was accused of skirting the debating process. Kerala Finance Minister Thomas Issac alleged that the Bills were introduced in the Lok Sabha as money bills.

A Money Bill need not be approved by the Rajya Sabha, where the Centre had already faced high-pitched protests from opposition during the passage of its controversial farm Bills.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.