Inside Motihari’s District Hospital: Screams, Negligence, Discrimination

Manu Kumari, eight-months pregnant, is forced to go outside to get ultrasound done while her pervasive abdominal pain stays.

It is 12.40 on Sunday, August 4. The state of affairs in the premises of Sadar Hospital, Motihari [East Champaran] is relatively slow as compared to the weekdays. Private ambulance drivers are relaxing, they unanimously say it is “chhuti ka din (holiday)” for most of them and the hospital staff.

However, this is not the situation for the patients here. Hargen Sahani, in his late sixties, has been discharged. He is sitting on a raised circular platform near the exit of the hospital. He had had serious asthmatic complications on the day (July 29) he was referred here from the Primary Health Centre of Chakia block. A resident of Bherkhiya Tikuliya village, he says, “I could not inhale…I thought for once that those were my last breaths…I had to wait till Monday to be admitted?”

Hargen, 68, is a BPL card holder but it did not help him get any discount on medicines.

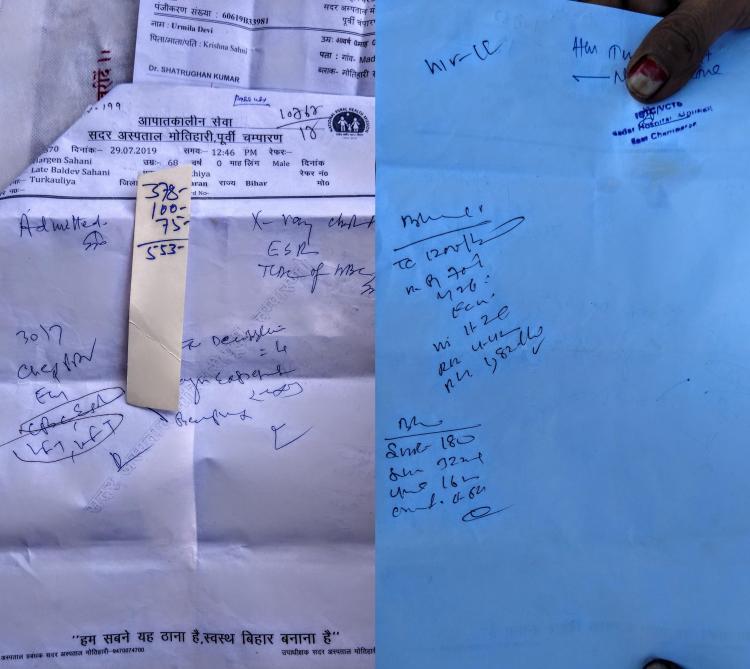

Ramavati Devi, Hargen’s wife, says angrily in a blend of Bhojpuri and Maithili, “Uhan ta jae ta ja ta mar ke beglai deihel (If we go there [PHC, Chakia], we are most likely to be kicked out.)” Ramavati had just returned after buying some prescribed medicines for her husband. She paid Rs 553 with some money borrowed from her relative. Moreover, the receipt of medicines, provided by the government-approved medical store inside the complex, is just a small piece of cardboard with dimensions 1.5 cm x 7 cm. There is no printed slip for the Blood Count (BC) report, the counts are written on the back of a hospital ticket.

“We lost one bigha of maize crop due to flash floods this year. Now our lives will run on debts till Rabi revives our hope,” adds Hargen. He shows us his BPL (Below Poverty Line) card, exclaiming that “it contains no value when a starving poor has no free healthcare to his rescue.”

Urmila Devi of Madhubani Ghat village is the mother-in-law of Ramavati’s daughter. She had come to help Ramavati as Hargen’s health continued to be critical. Urmila was the local executive of Jeevika, an initiative by Bihar government for poverty alleviation through social and economic empowerment, in her village. But she hasn’t received a single penny since 2014. “I had a skin problem for a long time. When I told doctors here [Sadar Hospital] that I am associated with Jeevika and non-treatment of my skin condition might hamper the progress of the programme, I was ridiculed,” she recounted. Urmila alleged her plea was dodged by a doctor who said: “Yahan Jeevika ka koi awkat nahi hai (Jeevika has no value here).” Now, she has been prescribed Avil 50, i.e. Pheniramine Maleate tablets. It will cost, Urmila says, Rs 1,000 a year. She said she recently paid Rs 500 as ‘bribe’ to access the flood recovery payment of Rs 6,000 for last year. “Corruption is quite ubiquitous here, whether it is village body or district hospital,” Urmila alleged.

Urmila is associated with Jeevika, but she was availed no help in Sadar Hospital. As she stayed from her village for a week to get her chronic itching treated, the works assigned to her under the program remained stagnant.

Moving to the Maternity Ward, this reporter spotted a pregnant woman whose screeching could be heard from a distance. “Bacha laga login…mar jaem…naikhe chalal jat…riksha joda login (Please, save me…I will die…can’t walk anymore…get a rickshaw for me),” wailed Manu Kumari, who was eight-months pregnant woman. She was asked by the doctor to get an ultrasound done. We learn that ultrasound facility in the hospital was closed on Sundays. We helped her find a facility near the hospital but midway down the road, her companion said, “She [Manu] is unable to bear the pain. We do not know why. They [doctors] do not want to admit her to avoid further hitches in her delivery, that is why they are finding excuses and pushing us to go to private hospitals.”

We immediately returned to the Maternity Ward to get Kumari admitted. The reserved police initially denied them entry, but after our intervention, let them in.

NewsClick then visited the Emergency Ward. A girl sitting on the floor, adjoining the emergency ticket-window, drew our attention. People surrounding her told us that she came with her family members who were physically attacked at home. When we asked her, Punam Kumari, 12, admitted having received blows on her head. As there is no public helper in the emergency ward, only middlemen, a kind lady after listening to our conversation helped her in getting an emergency ticket generated. We followed Punam to the office of the doctor on duty, who tried to put off her treatment; his junior staff began advising her family members that “the treatment will lure her name in criminal case”. Somehow, the doctor wrote some medicines and Punam was taken inside a treatment ward.

While we were waiting, the doctor left half an hour before the charted duty time slot, saying he had a meeting to attend. Meanwhile, Punam and her family members headed to the doctor’s office, where a person applied a check mark on the emergency ticket and asked Shikander Mahto, Punam’s distant relative, to fetch the prescribed medicines. On reading the ticket, we found that the listed medicines were essential ones and should be in the hospital’s stock.

Although we were spectators, we entered the room, which led to an altercation as an ambulance staff and an emergency staff tried to coerce Punam into admitting that she was given an injection, which she repeatedly denied.

When countered by us, they denied allegations of coercion and changed the topic. “We are under high pressure. We are also humans and may make mistakes,” they said.

The staff was not wrong. There was scarcity of staff, no doctor on duty to attend to patients brought into the Emergency Ward for an hour. Three ward staffs, equivalent to nurses, manage emergency cases if the doctor is not present.

Punam was finally given an injection, but other medicines were not available. The noticeboard of the office of the medical superintendent of Sadar Hospital, last updated on August 3, showed almost half of the 193 essential indoor medicines as “unavailable”.

Mogali Mahto, Punam’s father, said they spent Rs 1,900 on their journey from Belwa Piprapati village in Ramgarhwa block after the condition of his wife, Sona Dev,i deteriorated. Asked about ambulance, he said, “If the local police did not come after the deadly attack, how could we expect an ambulance?”

Amerika, Mogali and Birwali [left top] are hungry, however, they come to find that cafeteria [bottom] is closed; Urmila and Ramavati wait for a rickshaw [top right].

After Sona Devi’s condition normalised to an extent, the Mahatos went to look for some food, but the canteen was closed. The cafeteria has been defunct for more than three years.

We then catch the screams of Phulena Sahani, in his 60s, who has been referred from Ranjita Harsidhi to the Emergency Ward of Sadar Hospital after being assaulted by local villagers. With him is his son. Sahani cries after each step he takes but neither hospital staff nor the police come forward to help. His case is now being handled by a nurse.

Phulena Sahani [is] being shifted inside the emergency ward which functions in an unhygienic condition.

Seeing us inside the treatment facility of the Emergency Ward, the staff member started cleaning the bed. However, he had not worn gloves. Also, we could see blood is strewn across the floor. It was 2:30 pm, but the duty doctor slotted between 2PM and 8PM, was yet to preside.

We found that out of 70 positions for doctors, more than 40 seats were vacant in Sadar Hospital, Motihari. The hospital has only three female doctors, one pharmacist and one doctor specialised in orthopaedics who comes from PHC of Mehsi block. An insider, on the condition of anonymity, said the hospital had been reduced to a post-mortem and injury ward. We also learnt that a doctor never sees a patient whose ticket slip bears the name of another doctor. If the assigned doctor is on leave, the patient has to wait till he or she resumes work.

There is no supply of clean water to the patients. We failed to find water filters in the hospital complex. Even if there was any, it was away from public view and thus, inaccessible for common people. A handpump under the shade of cafeteria is used by the visitors and patients for the drinking and cleaning purposes.

The cash memo provided by the medicine shop in the hospital complex[left]; blood test results[right] generated by the hospital authority.

The district recorded a perfect zero on AES recovery rate, much to the chagrin of “Hum sab ne yah thana hai, swastha Bihar banana hai (We have pledged to make Bihar a healthy state)” – the slogan of the Health Department, Government of Bihar, which is inscribed on every prognosis slip. Six suspect cases of AES/Hypoglycaemia were brought dead to Motihari’s Sadar Hospital this year. East Champaran faced 12 AES deaths, only to come third behind Muzaffarpur and Vaishali with 130 and 19 deaths, respectively.

Even the worst cases sound normal in this district hospital, people appear to have got accustomed to medical negligence as an innate feature of the impenitent governmental ecosystem. As the despairing poor have no means to visit private doctors, they have no other option in hand.

Update: While Sona Devi's situation remains critical, the hospital administration forcibly got the signature of her husband Mogali Mahto on the discharge papers, on the morning of Wednesday, 07 August 2019. Superintendent of Sadar Hospital has refused to talk to NewsClick. Helpline numbers too remain inaccessible to lodge a complaint.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.