India’s Second ‘Wave’: Of Short-Term Measures and COVID Fatigue

Representational Image. | Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

With more than 40,000 new COVID-19 cases being consistently recorded in the country at the moment, the pandemic is once again rearing its head in India. India had hit a peak in terms of daily cases in mid-September 2020, with about 98,000 in a single day. The cases gradually decreased, and after hitting a low of about 7000 cases in early-February 2021, the country is preparing to brace itself for a second round of increase in cases. In some states a sort of second ‘wave’ of the infection has been declared officially.

While Europe and the United States had experienced the second waves during the months of October and November last year, India as a whole may be inching towards its second phase now. The global experience with the re-emergence of cases has been varied, with some countries better able to deal with a rise in cases while others fared worse.

However, countries which have been able to reduce transmission and mortality after the first wave – China and Slovakia – had initiated vigorous testing and tracing, and then quarantining and treating. In India, on the other hand, the testing continues to be abysmally low even after more than a year of grappling with the pandemic. With a total population of about 136 crore, only 17% of the population has been tested so far. It is another matter that within this fraction there have been reports of fake entries.

Trajectory of Cases – India and States

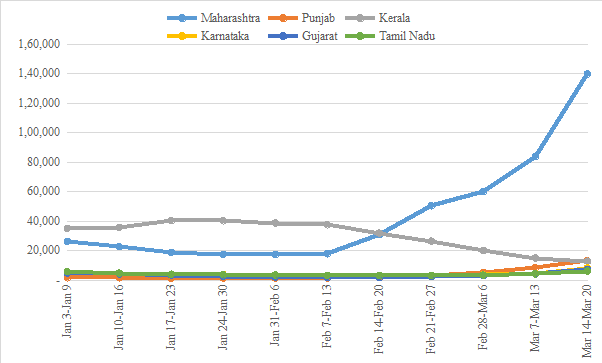

In terms of numbers of new COVID-19 cases, the top six states at present are Maharashtra, Punjab, Kerala, Karnataka, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu.

Figure 1: Weekly New Cases – Top Six States (as on March 20, 2021)

There has been a sharp increase in the number of new cases in some states like Maharashtra, where new COVID-19 cases have peaked again, over and above levels experienced last year, when the pandemic had hit hard. Most of these states have followed the trajectory of all-India figures, except for Kerala. The general pattern of emerging cases was a peak around September-October 2020, then gradually declining and hitting a low around January-February 2021, and now rising again in March this year.

The experience of Kerala has, however, been different. While cases in Kerala peaked in October 2020, they never came down drastically. The number of emerging cases plateaued and have been gradually declining throughout. While there appears to be a rising trend for weekly new cases, they are on a decline in Kerala. This may be attributed to a consistency in the state government’s approach and continued adherence to public health measures.

Looking at districts reporting the highest number of daily new cases, we see that both urban and rural districts feature in the list of top six districts – all belonging to Maharashtra.

Table 1: Top six districts in terms of daily new cases (as on March 20, 2021)

Can it be called a Second ‘Wave’? Does an Epidemic Behave any Differently?

According to Prof. Satyajit Rath, Faculty, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune, looking at the progression of epidemics as ‘waves’ is not helpful because the implications then are that it is sort of “…uniform, and that it will ‘soon recede’; neither of which is comfortingly correct, in fact.” According to him “while there are growing numbers of cases nationwide, like all epidemics they are the result of a series of local outbreaks... and in neighbourhoods that were not as severely affected in last year’s ‘wave’. This is very much how a respiratory virus epidemic would be broadly expected to spread.”

Prof. Rajib Dasgupta, Faculty, Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, Jawaharlal Nehru University, pointed out that “second waves have been experienced in most countries, and are only expected as this is an acute respiratory infection, which are typically propagated epidemics that are marked by waxing and waning.”

As another round of curfews and closure of public spaces are being announced and enforced in the affected regions, a report by the Central team sent to the worst-hit states like Maharashtra points to the lack of adherence to “COVID-19 appropriate behaviour” among people, both in rural and urban areas, and lack of required efforts to track, test, isolate cases and quarantine contacts.

In Europe, epidemiologists attributed the substantial second wave to loosening of both government restrictions and individual precautions, reflecting the struggle to balance the spread of the virus and returning to normalcy in public life. In the case of India, Prof. Rath calls it “epidemic fatigue” that seems to have contributed to the current increased rate of spread. There is a fatigue at the individual level reflected in reduced adherence to measures such as physical distancing and using masks.

However, the more serious fatigue that he pointed towards is “a form of fatigue or wishful thinking at governance levels, which keeps treating the epidemic as a short-term crisis. This has meant that all measures, whether health-related ones or the economy and livelihood-related ones, have been short-term – short-term hospital facilities, short-term additional contractual health workers, short-term public messaging and information provision, short-term funding, you name it.”

COVID Variants in India – How Likely a Threat?

According to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s (MoHFW) response to a Rajya Sabha question there are three new variants of SARS-CoV-2 which are of concern and have been reported in India – the UK variant, South Africa variant and Brazil variant. As on March 4, 2021, a total 242 samples have tested positive for different variants in India, but no case of re-infection by these mutant variants of SARS-CoV-2 virus has been reported from India so far.

Prof. Rath explained that “it was quite likely that, eventually, the virus population will change as variants get selected due to growing frequencies of vaccination (or indeed natural infection)”. He contended that as the emergence of the current outbreaks seems to be in localities that had not been severely affected last year; it is unlikely that there was an emergence of immune-resistant virus variants.

According to Prof. Dasgupta “Coronaviruses will continue to mutate and give rise to new variants. Genomic characterisation is constantly being tracked in order to identify and address variant forms, and specifically whether the newly emergent ones are more infectious and/or cause more mortality.”

In India, a genomic consortium of ten regional laboratories with National Center for Disease Control as the apex laboratory have been established to perform genomic sequencing of samples from positive travellers and five per cent of the positive test samples from the community.

As far as the global response is concerned, Dr. Chandrakant Lahariya, a public policy and health systems expert, pointed out that despite warnings from epidemiologists and infectious-disease experts, the required preparedness across countries had been deficient and that countries responded only when the pandemic hit them, all the time being under the impression that they were sufficiently ready to deal with it.

Given the bitter experience with the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Lahariya called for putting these past learnings into practice to reduce such severe impact in future. One only hopes that in the times to come governance systems would respond with sustainable and long-term solutions and invest more in better epidemic preparedness.

Peeyush Sharma and Pulkit Sharma complied the data for this piece.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.