Delhi Police in Court: Hum Kagaz Nahi Dikhayenge

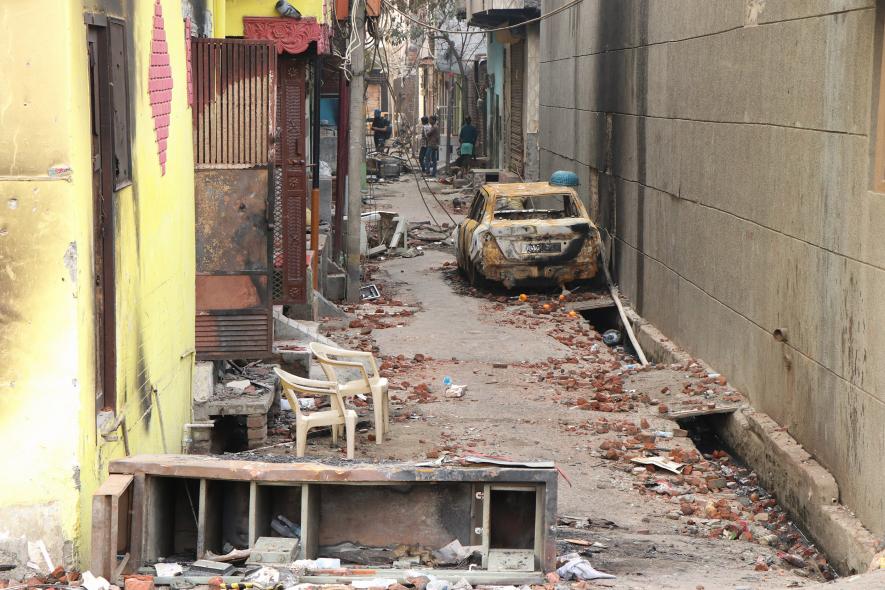

The wheels of justice are moving very slowly for sixteen people who according to Delhi Police conspired to unleash communal violence in north-east Delhi in February. An absurd fight over photocopies of the chargesheet related to this alleged conspiracy is needlessly delaying their trial. Nine months have passed since Delhi Police registered FIR No. 59/2020 in the case. Close to four months back, on 17 September, a special court took cognizance of the chargesheet prepared by the police.

Ordinarily, when a chargesheet reaches court it marks the conclusion of investigation and beginning of the trial. Ironically, in this case, the chargesheet itself has become a reason to delay the trial. This is because Delhi Police has been claiming that its 18,325-page chargesheet—the rough equivalent of 52 copies of the original Constitution of India written by Dr BR Ambedkar—is so bulky and voluminous that the exchequer cannot afford to photocopy it for each accused.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation puts the cost of photocopying 18,325 sheets of paper 16 times (for Re.1 per page) at Rs.2.93 lakh. Delhi Police has been refusing to spend this paltry sum, even though it has characterised this case as a massive conspiracy to defame India by sparking a violent episode in which fifty people died during United States [former] President Donald Trump’s trip to India.

The wait for their trial to begin is seemingly interminable for the accused, because Delhi Police has invoked strict provisions of the Indian Penal Code, UAPA and other laws in its FIR and chargesheet, which make securing bail virtually impossible. For example, one accused, Ishrat Jahan, complained that her back is injured after a fall in jail, but she was not granted bail. Therefore, all but the three have got bail in this case face the vicissitudes of incarceration though their trial is on hold.

Legally, all accused persons have a right to a copy of the chargesheet on their case. They are supposed to get it when they appear before the court on the summons of the police at the time of filing it. Yet, for an entire month—21 September to 21 October—the police argued against it. Initially, it asked the special court for 15 days to secure “sanction of funds” for the photocopies. The sessions judge hearing the case was “not impressed” by this argument. Then the police insisted that the pen drives containing the chargesheet—which it has given to each accused (or their lawyers)—would have to do. All this while, lawyers for the accused kept appealing to the court for physical copies of the chargesheet. This is because prison inmates are not permitted to access computers and so cannot see what the charges against them are.

This has already caused hardship to the accused and those representing them. For instance, at a trial court hearing before Christmas eve—three months after the chargesheet was filed—one accused, Umar Khalid, said he never saw the chargesheet. “I am only getting excerpts of it from newspapers,” he said. His lawyer Trideep Pais told the court, “Your honour, I cannot give him the soft copy in jail.” He added, “They [the accused] have suffered a disadvantage. They are in custody, they don’t get a copy of the chargesheet, and they don’t get a trial.”

Sequence of events:

On 21 September, the sessions judge ruled that as per section 207 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), a physical copy of the chargesheet and other documents in it “has to be furnished” to each accused by the police, and not [just] a soft copy. In subsequent hearings, there was insistence on compliance. On 21 October—over a month after the chargesheet was submitted—the court ordered, “the law mandates a hard copy”, so every accused person must get one “by the next date, without fail.” Delhi Police dithered. The matter dragged on to November.

At 10.09 am on 3 November, minutes before a crucial hearing on the issue, the defence lawyers received an email from Special Public Prosecutor Amit Prasad, who is the advocate representing the State, or prosecution. The subject was “NOTICE OF MOTION” and inside was the copy of a fresh petition: The police had escalated the photocopy issue to the Delhi High Court, where it pleaded on 4 November that the special court’s order for physical copies should be “set aside”. Hearings in this case began on 11 November.

The paradox is that the police are spending their supposedly meagre resources on court fees, lawyers’ appearance fees and print-outs of their new petition, to press the sole point that the State cannot afford photocopies of its existing paperwork.

When the High Court learned that the accused have not got copies of their chargesheet, it stayed the trial. “The stay would have been imposed by the High Court because without a chargesheet the accused would not know what the case against them is. Without it, an accused cannot make a serious case for discharge or claim innocence,” says Sanjay Hegde, senior advocate at the Supreme Court. “That is why this matter of soft and hard copies of a chargesheet needs to be settled in a court of law,” he says.

The result of the stay is that defence lawyers are free to pursue regular matters in the special court on behalf of their clients; seek bail, file applications related to their health and safety in jail, permissions to get reading material or interact with families, etc. But the actual trial— framing of charges, cross-examination of witnesses, anything that could prove or disprove the role of the accused in an alleged conspiracy—is on hold.

Typically, when a trial is held up and once the evidence is locked in a chargesheet, everybody jailed in connection with that case can seek bail. Yet even after the chargesheet was filed, one accused, Natasha Narwal, was not granted bail. The reason is the serious charges against her and others, in several FIRs, but in this case there is an additional roadblock: Delhi Police is still continuing its investigation into an alleged conspiracy and has filed a supplementary chargesheet. As the special court has already ruled that all accused must get physical copies of chargesheets, it obviously cannot change its position on the supplementary one.

“The prosecution has gone to the High Court on this point and now the High Court has stayed the trial on this point. I have to pass an order on the supplementary chargesheet, which is a part of the main chargesheet. So, I am not sure how to provide you a copy,” the sessions judge, Amitabh Rawat, wondered aloud during a hearing in December. He was responding to defence lawyers, who had asked if they would get physical copies of the fresh chargesheet or a new pen drive. After some to-and-fro, it was decided, sort of, that the High Court has stayed the trial and the photocopy issue was yet to be decided, but nothing stops lawyers from getting soft copies of the supplementary chargesheet.

“Actually, this trial will be one of the most scrutinised legal battles. Maybe the police think they have not done a good enough investigation and want to delay proceedings. The photocopies are an excuse to stall the trial. Or maybe it wants to plug loopholes in its investigation to avoid loss of face during the actual trial,” says one of the defence lawyers, Ritesh Dhar Dubey.

At the moment, courts are in recess. When hearings resume in the High Court, both sides will present arguments on the photocopy issue. It is impossible to predict when this case will conclude and the stay lift.

What matters is that this is not the only legal tangle arising because the police have filed an encyclopaedic chargesheet. Weeks after Delhi Police gave defence lawyers pen drives containing the original chargesheet, it asked for them back. It admitted to a blunder and blamed the chargesheet: the document is so “very lengthy, bulky and voluminous” that we forgot to remove from it the identities of its protected witnesses and their disclosures, was the basic argument.

Arguments of Delhi Police before trial court and High Court:

In September, Delhi Police claimed in the special court that the Information Technology Act, 2000, deems certain electronic records as “documents”, and that this provision overrides the CrPC. The special court disagreed, and ruled on the basis of the proviso to section 207, which says that if a document is very voluminous, then the accused or their pleader are allowed to personally “inspect” it. The term “inspect”, the judge said, can only apply to physical or hard copies—not information in a pen drive. “So, the investigating agency [Delhi Police] is bound to supply hard copy” to the accused, he said, adding, “Not every accused would be comfortable with a soft copy.” Indeed, some accused in this case are from underprivileged backgrounds—Asif Tanha worked at a tea shop to fund his education, for example.

Besides, as Hegde says, “Getting a physical copy of the chargesheet is a matter of the rights of an accused.”

Before the High Court of Delhi, the police insisted that the CrPC was enacted in 1898, 61 years before photocopy machines were marketed. Therefore, “to equate the word copy [in the CrPC] with photocopy is grossly incorrect”. It said the magistrate—not prosecution—is duty-bound to provide copies of the chargesheet, but this begs the question why Delhi Police bothered to provide pen drives to defence lawyers in the first place. The police complained that the trial court ignored how “voluminous” their chargesheet is, that photocopying it will “add extra financial burden on the State Exchequer”.

Oddly, it was then argued on behalf of the police that there is “no dispute or quarrel with the settled principle” of “general law” that a “hard copy is to be made available to the accused persons”. However, the proviso to section 207 is “an exception”. So, if documents are voluminous, then an accused can simply inspect it. In short, Delhi Police has sought exemption from providing photocopies in this case—not every criminal trial. Still, it is a chicken-or-egg situation, for the accused are not allowed to access computers in jail, while some lawyers, who applied to jail superintendents for permission to “view the chargesheet on a computer that is not connected to the internet”, also seem to have been ignored.

All this is happening because Delhi Police does not wish to burden the exchequer with Rs.3.29 lakh. An ordinary chargesheet is a few hundred pages, here it is an extensive report. No wonder some defence lawyers see in its size an effort to throw every charge possible at the accused in the hope that some will stick.

“Until now, all over India, police have given hard copies of their chargesheet. This is the first case in which they say they cannot do so,” says advocate Mehmood Pracha, who represents some accused. “In fact, the chargesheet does not have the weight of evidence on its side and I think in the end, the police will say their protected witnesses were leaked, and that is why their case did not succeed,” he says.

At one point in the High Court, Delhi Police offered that defence lawyers could pick up the photocopies from a designated photocopy shop, and it would pay. “Who will vouch for the authenticity of copies we pick up from some photocopy shop? We have no choice but to demand the police stick to established procedure,” Pracha says.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.