Patrice Lumumba: Belgium to Return Remains of Assassinated Congo Leader

Patrice Lumumba, Congo's first prime minister, was assassinated by a firing squad as Belgian officials looked on

"More than 60 years of pain": That's how Juliana Lumumba has described her family's life.

The 67-year-old politician and daughter of Patrice Lumumba, Congo's former prime minister, has been waiting decades for Belgium to return the known remains of her father — a tooth and finger bones.

"As a family, we have to move on and we can only do it once we bury our father's remains in peace," she told DW by phone from Congo. "So far, the handover process has been very bureaucratic and coupled with the pandemic, we are still waiting for his tooth. Hopefully this year Belgium will hand over what is rightly ours."

On June 20, Belgium will officially present Patrice Lumumba's tooth to his family members at an official ceremony in Brussels.

While the tooth is just a body part, it also symbolizes a dark period in the history of both Belgium and Congo, its former colony; a period that Belgium is still trying to unpack and accept, according to Juliana Lumumba.

Lumumba considered a 'threat'

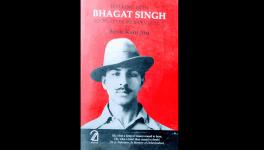

Patrice Lumumba rose to power to become Congo's first democratically elected prime minister in 1960.

"I remember going to the office with him as a 5-year-old girl and watching him work," Juliana remembered fondly. "He was a man who personified democracy during colonialism."

But Lumumba's tenure lasted less than a year after his rival, Congolese President Joseph Kasa-Vubu, attempted to dismiss him. Amid the chaos, a coup led by Colonel Joseph Mobutu overthrew the prime minister.

In December 1960, Lumumba (right) and Senate Vice President Joseph Okito (left) were arrested

Imprisoned under Mobutu's dictatorship, Lumumba continued to urge democratic and communist values. But this also made him a threat to Belgium and the United States.

"They feared he would gain support from the Soviet Union back then. This was the peak Cold War era," Belgian writer Ludo De Witte, who wrote the book "The Assassination of Lumumba," told DW. "The Belgian government also considered Lumumba's values as a threat to their fundamental interests in Congo."

This fear led to Lumumba's murder in January 1961. He was shot dead by soldiers belonging to the breakaway Congolese state of Katanga, as Belgian officials watched.

"Once he was executed, a Belgian police officer named Gerard Soete and his brother took charge of destroying Lumumba's body to hide all evidence of his murder," said De Witte. "They cut his body into pieces and dissolved the remains in a barrel of sulfuric acid."

"But Soete kept some remnants of Lumumba's body with him and decided to bring it back home to Belgium as a sort of 'hunting trophy'," he added. "This shows what elites can do when they consider you a threat."

Impact of his death

After De Witte published his book analyzing Lumumba's murder in Dutch in 1999, Soete came forward and confirmed his role in the cover-up.

A Belgian parliamentary inquiry launched in 2001 found that the country was morally responsible for Lumumba's death.

"The execution occurred in the presence of Katangan ministers and was carried out by Katangan gendarmes or police officers, in the presence, though, of a Belgian police commissioner and three Belgian officers who were under the authority, leadership and supervision of the Katangan authorities," the inquiry stated.

The inquiry also added that the Belgian government did not protest the unlawful execution of Lumumba, nor express regret or disapproval in relation to it.

Following the inquiry, Belgium's then-Foreign Minister Louis Michel conveyed his "sincere regrets" for his country's role. But the country continued to hold on to Lumumba's tooth, which has been kept at the Belgian prosecutor's office in Brussels.

Only in 2020, at the height of the global Black Lives Matter movement, did Belgium's King Philippe respond to a letter from Juliana Lumumba and agree to return her father's remains.

"Getting his remains is important for us as a family," she told DW. "But it has a bigger impact on the people of the DRC because his death was the assassination of democracy in the country. He was killed for his values and still remains in the minds of the people."

The Congolese diaspora in Belgium shared similar sentiments, according to Anne Wetsi Mpoma, an art historian and independent curator.

"Patrice Lumumba fought for the freedom of his country and the Congolese community never really recovered from that loss," Mpoma said. "Moreover, considering the crisis in the country today, he is really like a symbol of peace who people look up to at a time when most of the leaders in African countries today choose themselves instead of choosing their people."

Is returning the tooth enough?

In 2018, following a request by the Congolese and other African communities in Belgium, the Brussels city council announced that a public square would be named after Patrice Lumumba.

The square in question is in the middle of a bustling shopping street in Brussels and has become a space where people gather to protest against racism, according to Aliou Balde, an activist from Guinea.

"For many Africans, Patrice Lumumba is our impulse to fight racism, police violation and call for decolonization," he told DW. "Just like a car needs petrol to function, Patrice Lumumba is our source of energy to fight for our rights."

A event to mark 60 years since the death of Lumumba and his allies was held in Brussels in January 2021

But for De Witte, public squares and the return of relics mean nothing — and he said the Belgian government is still indifferent to its dark history.

"The country has still not taken complete responsibility for his assassination. Yes, there were apologies and regrets but it is all passive. More importantly, the death of Lumumba led to decades of dictatorship and civil upheavals which are clearly responsible for the state the country is in today," he said.

"So I think we have to get apologies, but also more political, financial and symbolic support to unpack this dark period effectively," he added.

Art historian Mpoma shares that view, and said Belgium and Europe also need to start having real conversations to unpack the brutalities of colonialism.

"From the moment people start to recognize that deeds in the past were wrong, they will also be obliged to see the consequences of those deeds today," she said.

Edited by: Stephanie Burnett

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.