Citizenship Amendment Act: Who is an Indian Citizen?

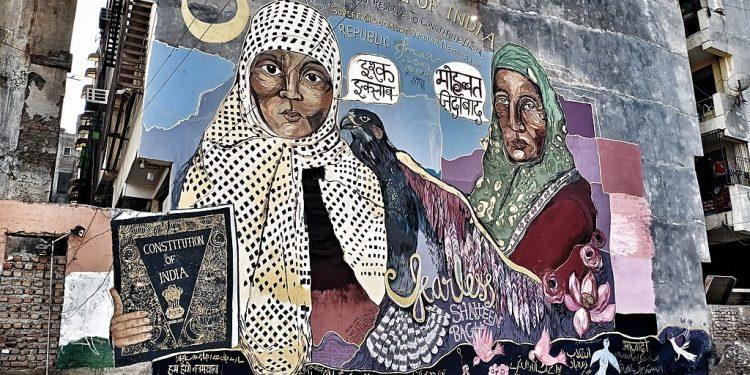

Graffiti in Shaheen Bagh, Source: Common Creative

The Citizenship Amendment Act of 2019 created an uproar across India for its discriminatory approach in granting citizenship. ACHIN VANAIK writes on the development of the legal idea of Indian Citizenship since Independence.

——–

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) was passed in both houses of Parliament on December 10 and 11, 2019, and came into force from January 10, 2020, when it was formally notified. This Act spurred a prolonged public controversy and protest because of the many questions, implicit and explicit, that were raised by critics saying that it violated the substance of the Indian Constitution. Till now the Supreme Court has not ruled on the matter.

The CAA provides for fast-track naturalisation for non-Muslim religious minorities from the three neighbouring Muslim majority countries of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh if they arrived in India before 31.12.2014 and have been here for five years. For them, as of 31.12. 2019, they would have become eligible for immediate naturalised citizenship Moreover, as already announced by the government, there is to be an all-India National Population Register (NPR) to identify “doubtful citizens” and thereafter a process of carrying out a National Register of Citizens (NRC) which will pronounce final judgment on the status of such “doubtful citizens” who have insufficient documentation of their status.

For the first time, religious discrimination has been embodied in a law pertaining to Citizenship. To be a Citizen is to have the right to have various rights—hence its vital importance.

Those deemed illegals can be subjected to prosecution, detention, expulsion or other forms of punishment.

The issues raised are the following:

- In the three countries to which it applies, non-Muslim minorities are axiomatically deemed to be collectively suffering religious persecution. It is not a question of individuals having to prove that they have been religiously persecuted. Certain Muslim sects like Hazaras (Afghanistan) or Ahmediyas (not deemed Muslim in Pakistan) are not considered to be persecuted on religious grounds.

- The CAA has been selectively applied to Muslim majority countries but not to the neighbouring Buddhist majority countries of Bhutan (where there are allegations of Christian persecution) or Myanmar (where Muslim Rohingyas are widely accepted as being persecuted) or Sri Lanka (where there are allegations of persecution of Tamil Hindus) or to Hindu majority Nepal (where there are allegations of Christian persecution). It would appear that Buddhist or Hindu majority neighbouring countries are not to be considered axiomatically guilty of persecution of religious minorities.

- Those non-Muslim minorities (which proportionately speaking are primarily but not solely Hindus or Sikhs) who arrived after 31.12.2014 can claim not to have documentary proof of their time of arrival precisely because of religious persecution and claim that they arrived before the cut-off date and hence would now be eligible for naturalised citizenship. Given the fact that they are by definition deemed to belong to a religiously persecuted group, it would seem fair to accept this at their word. Similarly, there is a huge number of Indian citizens who do not have minimal documentary proof like birth certificates (most births take place at home and not in hospitals) or passports or other required proofs of their status. The CAA provides an escape route of sorts to those non-Muslim “doubtful citizens” identified by the NPR and confronted by the NRC who can make a similar explanation for prior migration and ‘loss of documentation’.

- What are the basic implications of the CAA for the Indian Constitution whose ‘basic structure’ defends the principles of secularity and democracy? A necessary condition to be considered a secular state is that citizenship status and its associated rights must be irrespective of religious affiliation. This secularity of the state in law is also a necessary but not sufficient condition for being recognised as a democratic state in law. One can be secular—equal citizenship rights irrespective of religious affiliation—but there can be the absence of those minimal democratic rights that are a precondition for being considered a democracy of some kind. The founding of Kemalist Turkey is not the only example of a secular but non-democratic state. The Indian state and Constitution claims to be both secular and democratic.

What is given below refers only to this last issue and provides an actual timeline of the changes that have taken place in law with respect to the issue of citizenship status and associated rights in India. It starts from the end of colonial rule and the first laying down by the Constitution of how Indian citizenship is acquired and continues up to the current period of the inauguration of the CAA in the backdrop of the plans for carrying out NPR and NRC (currently held in abeyance because of the Covid-19 pandemic).

Here is a factsheet. Readers are left to arrive at their own judgments and conclusions regarding the CAA and its effects and implications.

(Credit: Diplomat Tester Man, Source: Common Creative)

Who Is An Indian Citizen?

January 26, 1950: By The Indian Constitution

The Indian Constitution clearly states that a citizen of India is someone who is born before Republic Day in the territory of Post-Partition India, is born before 26.01.1950, and was ordinarily resident for five or more years in this new India.

Someone who migrated from Pakistan to India before 19.07.1948 and straightaway registered as Indian, also qualifies as an Indian.

Any migrant after 19.07.1948 could register as Indian if one parent or grandparent was born in

undivided India.

There should be no religious discrimination with respect to migrants or non-migrants.

Such illegal persons no matter how long they have been in India can never become Indian citizens, nor can their children no matter that they were born in India or may have lived and been raised in this country for many years.

Let us look at the Citizenship Act of 1955: Six Ways of Attaining Citizenship

- Born in new India

- Born outside but father Indian citizen; after Dec. 10, 1992, if either parent Indian citizen.

- (iii) If of Indian origin (abroad) can register as an Indian citizen.

- (iv) Those married to an Indian citizen after some years of residence can get Indian citizenship.

- Can become a naturalised Indian citizen after 11 years of residence.

- (vi) People in territories acquired by independent India are Indian citizens, e.g., Goa, Sikkim.

Again, no religious discrimination

Check this out: July 1, 1987 Amendment to Citizenship Act:

If born after this date then to be an Indian citizen you must have one parent as an Indian citizen.

[Specific to Assam only—according to new Section 6A incorporated into to Citizenship Act, those coming from Bangladesh to Assam between January 1, 1966, and March 25, 1971, when Bangladesh declared itself an independent country) could get Indian citizenship after 10 years residence from when they arrived in Assam. No citizenship for Bangladesh migrants in Assam if coming after March 25, 1971.]

Again, no religious discrimination

First BJP-led government 1998/9-2004

In 2003-2004 the government makes an amendment to Citizenship Act stating that for those born after December 30, 2004, it is not enough if one parent is an Indian citizen. The other parent must prove that he or she is not an illegal person or a migrant. Such illegal persons no matter how long they have been in India can never become Indian citizens, nor can their children no matter that they were born in India or may have lived and been raised in this country for many years. Such illegals are subject to prosecution and or expulsion.

For detecting such illegals, a National Population Register (NPR) was for the first time brought in as mandated by Rule 4 of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) also introduced for the first time. The connection of NPR to NRC is intrinsic. The NRC was brought in by the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003.

You were considered illegal if:

- If you did not have proper travel documents or these were fraudulent.

- If you had no visa

- If you had overstayed your period.

However, another rule was introduced in this period— namely that Hindus with Pakistani citizenship were not to be considered or be designated as ‘illegals’ no matter what, and therefore not liable to being prosecuted or expelled under the Foreigners Act.

(Credit: Diplomat Tester Man, Source: Common Creative)

For the first time, a principle of religious discrimination was introduced.

Updating of NPR in 2010

The Congress-led UPA government introduced the Aadhar Card in 2009 and sought to update the NPR to collect data and to promote public adoption of the Aadhar Card which had to be applied for and not mandatory.

No religious discrimination

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Notification of March 26, 2018

This came in the first term of the BJP government. According to this, for the first time, it was stated that six minorities from three neighbouring countries, namely Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians, Buddhists, Jains from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan having long term visas, could now purchase one residential immovable property and also open non-resident bank accounts for the purposes of earning income derived from any activity in India. This would not apply to Muslims from these three countries.

Changes Made to Passport Fines for Visa Overstay on January 7, 2019

In the case of Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians, Buddhists, Jains from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, should they overstay their visa time periods they would be subject to the following fines: If overstaying by 1 to 90 days they would have to pay Rs. 100. If they have overstayed by 91 days to 2 years they would have to pay Rs. 200. If they have overstayed by more than 2 years up to 5 years they would have to pay Rs. 500. The respective fines for Muslims from these countries for the same lengths of overstay would be US $ 300, $400 and $500.

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of December 12, 2019

The CAB was introduced in 2016 but only after achieving a majority in both houses was it passed and became law and is applicable unless it is struck down subsequently by the Supreme Court. The same six non-Muslim minorities from the same three neighbouring countries as mentioned above, because they are deemed to be religiously persecuted, can if they came before December 31, 2014, get fast-track naturalisation to become Indian citizens. This would now be immediate since, by December 31, 2019, five years would have passed.

For the first time, religious discrimination has been embodied in a law pertaining to Citizenship. To be a Citizen is to have the right to have various rights—hence its vital importance.

(Achin Vanaik is a writer and social activist, a former professor at the University of Delhi and Delhi-based Fellow of the Transnational Institute, Amsterdam. He is the author of numerous books, including The Painful Transition: Bourgeois Democracy in India. Views are personal.)

This article was first published in The Leaflet.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.