China India Disconnected? The App Ban and Beyond

Image for representational use only.

India launched a ‘digital strike’ against China, (the words of Union Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad, not mine) blocking 59 Chinese apps on June 29, including Tik Tok which has over 200 million Indian users, and Wechat, the only communication channel between Indians and Chinese. At the time of writing Tik Tok is no longer accessible, Wechat, so far, remains alive (but qq.com links are blocked).

I wrote last week how the June 15 border clash barely registered in the headlines here. The app ban certainly made the headlines of several popular digital media platforms, especially taking notice of Atmanirbhar Bharat, and the surrounding nationalist rhetoric—after all, self-reliance and app bans is something very familiar in Chinese discourse.

But this issue is not about Chinese commentary. Instead I’d like to share some thoughts on this latest flashpoint, as a response to what i’ve been reading and observing coming out of India. I fear a China policy that brings more pain than gain.

The decision to ban the apps is economic retribution for the June 15 border clash and what the Government of India sees, with reasonable evidence, as aggressive behaviour by the the PLA to occupy territory in the Galwan valley that India claims. ( see issue #15).

Although GOI has used other arguments.

In its press statement the Ministry of Information Technology claimed the ‘sovereignty and security’ view exercised under Section 69A of the Indian IT Act:

in view of information available [that] they are engaged in activities which are prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of state and public order.

Later the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre expanded this to ‘privacy’.

There has been a strong chorus in the public space to take strict action against Apps that harm India’s sovereignty as well as the privacy of our citizen,”

“The compilation of these data, its mining and profiling by elements hostile to national security and defence of India, which ultimately impinges upon the sovereignty and integrity of India, is a matter of very deep and immediate concern which requires emergency measures’.

Unsurprisingly plenty of commentators have jumped on the privacy bandwagon too. India has yet to set up a data protection law to clearly address how Indian citizen data should be handled and where. What exactly is it that these 59 apps are not in compliance with?

It appears privacy is fought for when its framed at the state level, less so at the individual. Privacy has also become the new ‘national security’ boogeyman in international relations.

@pranesh Twitter

In truth its been coming. India has long flip flopped in global internet governance deliberations, but in recent years the Indian state has rallied around the idea of ‘data sovereignty’, which, ironically, borrows from China’s own concept of Internet sovereignty. I wrote back in issue 7 we may see more clashes between the two tech stacks. The government has rarely expanded on its vision in great detail so we must observe its actions, and the links to another larger vision Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) are becoming apparent. The app ban has been cheered on by some prominent entrepreneurs and investors, with some calling this the ‘digital Aatmanirbhar moment’. This goes far beyond China and the app ban but once again shows #ChinaIndiaNetworked.

I’d love to dig into this convergence, but another time, for now lets go back to the app ban.

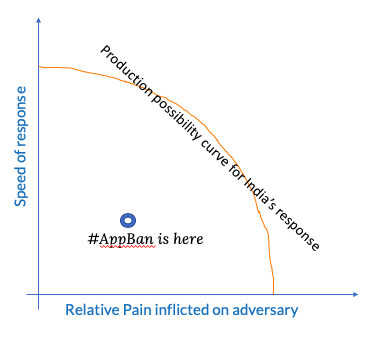

Only our top leaders are aware of what the situation in Galwan Valley really is and why it chose to react in the economic domain rather than military. There has been no shortages of takes and perspectives on the app ban over the past week. Ravish and JP took a swipe in their latest issue of Turnaround and I’d like to share Pranay Kotasthane’s well-articulated critique in his newsletter Anticipating the Unanticipated:

Coming to the response itself. What India has done is to address a problem in the military domain through the application of power in the economic domain, using the economic option that causes the least pain to the PRC. Such a response is likely to have zero deterrence effect on the CPC’s decision-making calculus. We just have a trial balloon in place of a proportional response….

Now, the relative pain factor. By using a weak instrument in the economic domain, India has ceded the advantage to the PRC. PRC is relatively stronger in this domain and use of economic instruments will come at a relatively higher cost to India.

Zoom out of the specifics of the app ban itself.

It seems clear there is a wider momentum building around a movement to reduce economic dependence on China, converging with economic policies to be reduce dependence on imports. Tik Tok may even be back in 15 seconds. But app ban is a signalling of intent that may be solidified in policy.

If the China-India balance scale at the start of the 21st century oscilated between cooperation and competition, it appears to be tipping firmly to one side. When seasoned China hands, like former Ambassador Bambawale, says, ‘we cannot let the rest of the India-China relationship continue as normal. It cannot be business as usual’, you pay attention.

A lot of the analyses and commentary has focussed on what India will gain from such a position—political autonomy, enhanced security, an advantage for Indian startups.

All this may prove to be true.

But as an advocate for engagement, because I believe in the long run people benefit more than they lose (putting my bias and assumptions out there in the open), I’d like to highlight what we stand to lose.

Pulling the plug on a promising tech partnership that was a new domain for China-India exchange and learning

The climate of confrontation will effectively put an end to the most promising area of China India exchange in centuries(!). Exchange, that I previously argued, could catalyse an Operating System (OS) upgrade for the relationship. My argument then was that for the first time since relations were put on ice after the 1962 war we began to see a circular flow of people, capital and ideas (see issue 7) moving beyond the rigid bilateral state-state led engagement. Tech is at the front and center.

Chinese companies designed for ‘Bharat’ i.e. the hundreds of million of young Indians in smaller cities, the ones that Silicon valley did not. Digital anthropologist Payal Arora in her book The Next Billion Users noted, ‘Chinese apps are co-designing the internet for newly online, mobile first users, who are mostly from a distinctly lower socio-economic background’.

The Ken reported this week:

“Chinese apps were far empathetic to this emerging markets user segment,” said Gupta. Because China had a huge user base of Android users who were also from lower-income segments, solving their problems became critical for these apps; and that helped them grow in markets like India as well. “Apps like SHAREIt and UC Browser solved for low internet speeds, limited data caps, low purchasing power, and discovery of content for new-to-internet users since they understood this target segment,” he added.

Chinese capital helped Indian startups and grew parts of the Indian ecosystem when neither Indian nor Silicon Valley investors were willing to build for a segment that that came with a high user acquisition and low revenue.

Chinese companies and VCs brought in somewhere between $6-8 billion between 2015-2018 into the hands of dozens of Indian entrepreneurs and tech companies including Paytm, MakemyTrip, Ola, Hike, Krazybee, Zomato, Gaana, Sharechat, etc. Capital in the hands of Indian entrepreneurs to grow and build Indian companies for Indians.

Yes, the app ban technically does not target Chinese investment, but the new added regulatory approval in April did that already, before the current climate.

Maybe the removal of the Chinese portion of the pie will be replaced swiftly by increased investment from other sources. Maybe the market has matured to the level that more Indian startups and investors are willing to cater to that segment. But its big piece of the pie to fill why did they have to wait until the Chinese left? Outside of the big players (most who already have Chinese investment) smaller Indian startups will feel the pain through less avenues for funding. By reducing competition we also risk the overall the health of the Indian ecosystem if large players, like Jio, for instance, simply become completely dominant across several verticals.

The ban censures Indians

Tik Tik is more than a Chinese app. Its users are across the world. Walling out Tik Tok de-facto censures 200 million Indians users from participating in the global media information space. It also effectively nationalises the accrued capital — followers and content— that many content creators worked hard to build and earn a living from. But none of ‘us’ will feel the pain so it wont register. Mitron and Roposo, the Tik Tok alternatives, are not global, and will not be able replace this income. Replicating Tik Tok’s recommendation algorithm in the short to medium term is not a given either.

Banning Wechat effectively closes the only communication channel between Chinese and Indians. Indian business folk and traders across so many sectors rely on the app to communicate with their Chinese counterparts. It will also affect thousands of Indian students, academics, and anyone who has cross-border ties.

This is yet another example of a paternalistic state removing agency from individuals to define what is good for them. Are we also setting a precedent for blocking and censorship that may be used in the future on other apps that are not Chinese?

Turning the clock back on people-to-people engagement

Going beyong the cash, tech engagement brings tens of thousands of Chinese and Indians in contact with each other. More Chinese travel and work in India. This builds relationships with people and the culture. In economics we have the phenomenon known as the money multiplier effect to describe the actual impact of money injected to the economy, a similiar effect is visible with each person who travels or works in India. I’ve met so many young Chinese professionals who come back richer from their experience and advocate for India among their friends and family. The heady talk of pan-Asianism may be dead but still engagement is the best way to weaken the effect of Chinese state media propaganda. Otherwise India will always remain a democratic neighbour that’s weak, poor, dirty, and chaotic and more easily exploited by Chinese leadership.

In trying to exact costs on the PLA, India has instead shifted them to some Chinese companies and people. We are mistaken to equate the Party state and people as one. Its undoubted the relationship between Chinese companies and the state are murky and very different to democratic political system. But we need more nuance in our thinking and frameworks.

India would benefit from having Chinese platforms and people more invested in India. Strategically, in the long run, the more China is economically dependent on India, the more India can use economic coercsion to exert some influence. Hitting the (future) valuation of Tik Tok, for instance, barely registers for the CCP. Rather than blunt bans we need tailored regulations and laws that balance security and economy interests of India and Indians, while building partnerships with other countries to raise the cost for aggressive behaviour.

I always look to the deep economic exchanges between China and the US and Japan, both rivals in different ways, and the opportunities it has afforded so many. Its created a human capital base in both countries who understand each other better, and a level of deterrence that keeps escalation from both sides in check. US-China relations would look even worse without it.

China’s aggressive behaviour on the border needs to be confronted. But I fear the route of attempted economic decoupling end these promising partnerships. Have Indian leaders really thought through the end game of open economic confrontation with China? The technology dependencies across the hardware supply chain stack is acute and if India wants to deliver on economic growth it needs to buy from China. Its mistaken to think that simply banning or not buying from Chinese companies will mean Indian firms will move up the value chain. We buy from China because it is in our interest to.

China’s AI ecosystem for instance was able to blossom because of planned investment into fundamentals like education and talent building, and capital made easily available to startups. As a % of GDP Chinese firms spend three times more than Indian firms on R&D. India needs to learn how China has built its ecosystem (Anyone willing to pay for a research project?) while building its domestic industrial capacity through deliberate, long term policy making and investment. Attempted decoupling now is unwise and hurts India’s own interests.

Ultimately good foreign policy creates is one that creates the best conditions for domestic growth. We need to chart a path that includes less economic suffering for Indians. I dont believe trampling on the early shoots of engagement is the way to go. Anyone else out there? please write in. We need more people working together to prevent the bottom from coming out.

ChinaIndia Networked is a newsletter by me, Dev Lewis, highlighting the networked relationship between the two regions at the intersection of technology, society, and politics. I’m a Fellow with Digital Asia Hub and Yenching Scholar at Peking University.

Follow me on Twitter or write to me at devlewis@protonmail.com.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.