Lockdown Gains for Adani Ports and SEZ

Image: Adani Ports

Mumbai: July saw the biggest private operator of ports in the country, Adani Ports and Special Economic Zones, take a significant step towards acquiring the Krishnapatnam port in Nellore district of Andhra Pradesh. While on July 7 , the company announced that it had initiated a plan to raise $1.25 billion (approximately Rs 9,300 crore) through dollar bonds to fund the acquisition, on July 23, the Competition Commission of India granted its approval to the deal.

In addition, according to a document seen by Newsclick, the company also raised Rs 1,500 crore through a debenture issue in April 2020.

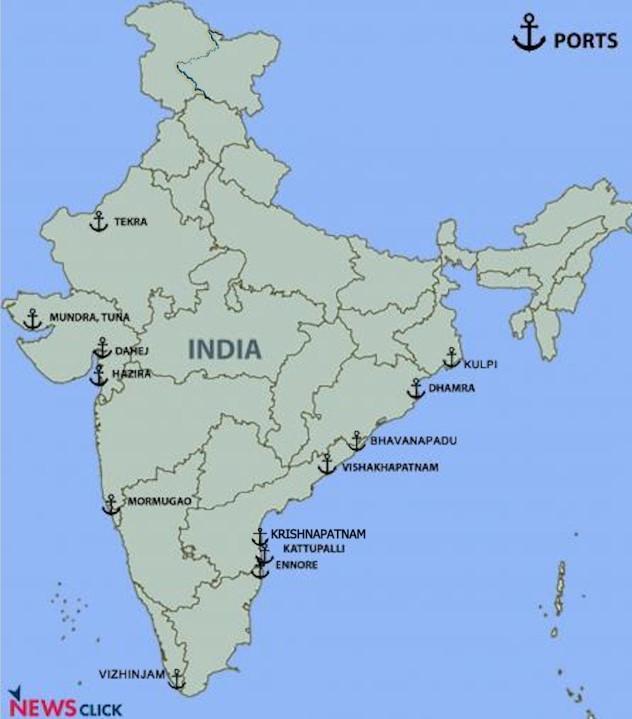

Once the Rs 13,500 crore acquisition is completed, Adani Ports will own the two largest privately-owned ports in India, along with nine other ports and terminals across the Indian coastline, further consolidating its position as the dominant private player in the sector.

The lockdown has been kind to Adani Ports. While it has not been immune to an industry-wide downturn due to a slowdown in economic activity, in the first quarter of the current financial year, from April to June 2020, its Mundra Port in Gujarat surpassed the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust in Mumbai to become the largest container port in India by volume.

Mundra’s ascent can be attributed, at least in part, to a significant policy change made by the Ministry of Shipping. In May 2018, the ministry changed the rules governing “cabotage” –the movement of goods along the coastline from one Indian port to another – of shipping containers.

At that time, this author had written that the decision was anticipated by stakeholders in the ports and shipping industries to benefit Adani Ports. Trends in the data of container volumes moved through Indian ports show that the expectation was not unwarranted. As explained in this article, with the Krishnapatnam acquisition, Adani Ports is now well placed to press home its gains due to the cabotage relaxations.

Cabotage Relaxations: Adani Ports’ Gains

In May 2018, the Ministry of Shipping issued a notification that relaxed restrictions on the movement of foreign ships engaged in transporting containers laden with goods for export/import as well as empty ones between and among Indian ports. The notification modified the Merchant Shipping Act, taking away the “right of first refusal” accorded to Indian shipping companies for coastal shipping in the export/import segment.

The cabotage regime, in its earlier form, was intended to protect and support the domestic shipping industry, and was in consonance with international policy standards adopted in comparable trade-dependent countries with long coastlines, including the US and China.

Significantly for India, the result of this restriction was that major international shipping lines preferred to dock their intercontinental carriers with Indian cargo at foreign ports in the region – particularly Colombo in Sri Lanka, Jebel Ali in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, and Singapore – and “trans-ship” the Indian cargo in smaller “feeder” ships to Indian ports, as this allowed them to use their own feeder ships rather than be forced to use Indian owned ships for trans-shipping cargo from major Indian ports along the Indian coastline.

The rule change, however, meant that international shipping lines could now dock directly at an Indian port – such as Mundra and JNPT on the west coast, and trans-ship cargo from there to other Indian ports closer to the final destinations, using their own ships.

This placed Mundra at an advantage over JNPT – not only did Mundra have higher quality onshore equipment and a faster turn-around time, two of the world’s biggest shipping lines had significant stakes in Mundra port, making it the preferred destination. Mediterranean Shipping Company of Switzerland and CMA-CGM of France, the second and fourth largest container shipping lines in the world, own two of the four terminals at Mundra.

According to data collected by the industry tracker JOC.com, Mundra’s trans-shipment cargo “soared 21 per cent” in the year following the May 2018 rule change, compared with the previous year. By volume, 750,491 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units, a measure used in shipping) of trans-shipment containers moved in and out of Mundra in the latter period, compared with 620,699 TEU previously.

With overall growth having fallen, the growth of 3% in Mundra’s volumes was attributable “almost entirely” to trans-shipment gains. Of a growth of 126,000 TEU over the previous year, about 115,000 TEU were gains in trans-shipment. This difference is depicted in the table below.

Further, prior to the lockdown, the growth in trans-shipment cargo had quickened between May and December of 2019. Compared with 61,000 TEU per month during May-December 2018, in the following year Mundra shipped around 71,500 TEU per month, reaching a total of 570,889 TEU. In the same period, JNPT saw only 88,805 TEU of trans-shipped containers pass through the port.

Lockdown Pains

The pandemic has hit the Indian shipping and ports industries hard. At JNPT, traffic declined by 26% in the April-June quarter, while Adani Ports announced that it had seen a 27% decline in traffic across its 10 ports, and an 18% fall in revenue.

Shipping companies and seafarers, too, were badly affected. A spokesperson for the Indian National Shipowners Association told Newsclick that certain decisions of the Ministry led to further pain being inflicted with Indian shipping companies having already seen their share in trans-shipment cargo fall from 70% to 59% in the 2019-20, following cabotage relaxation for foreign ships.

In particular, the spokesperson pointed out the notifications by the Directorate General of Shipping that prevented shipping companies from charging “detention charges” to their clients for the lockdown period. Detention charges are the cost an importer/exporter has to pay to make use of containers carrying their cargo beyond a fixed number of free days.

Pointing out that several Indian ports, led by Adani’s Mundra which was the first to do so, had declared “force majeure” on account of the pandemic, the spokesperson said this “led to longer delays at the ports with the contractual terms for time taken for handling and delivery of cargo having been suspended.” The “unpredictable contract environment” created as a result, adversely affected Indian companies.

Meanwhile, with lockdowns being implemented across the world due to the pandemic, many seafarers found themselves stuck offshore or at foreign ports. At a recent web-conference, David Joseph, Deputy Director General of Shipping, said the directorate had facilitated the transfer of over 70,000 seafarers, for which chartered flights as well as Vande Bharat repatriation flights were put to use.

Gains from Krishnapatnam

The acquisition of the Krishnapatnam port is of particular significance for Adani Ports in light of the cabotage relaxation. The Shipping Ministry had declared in May 2018 that the move was intended particularly to reduce India’s dependence on trans-shipment of Indian cargo from foreign ports, such as Colombo, Jebel Ali and Singapore.

According to JOC data, in the case of Colombo, the intended effect is already being witnessed. Indian trans-shipment cargo fell by almost 1 million TEU between 2018 and 2019 (from 5,518,742 TEU in 2018 to 4,644,904 TEU in 2019.

This shift in cargo has also led to a blossoming of ports on the east coast of India. Traditionally, Indian shipping has been tilted towards the west coast, with Mundra and JNPT being a port of call for international shipping lines. The majority of the ports on the east coast were primarily being engaged in feeder activities.

The cabotage rule change opened an opportunity for major shipping lines to call on ports on the east coast as well. A new shipping service, named the South-East India – Europe Express service, was launched in November 2019 by a consortium of international shipping lines, including Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd, Ocean Network Express of Japan, Yang Ming of Taiwan and Cosco-OOCL of China, with a weekly carrying capacity of 58,500 TEU. The service that would call on ports in Vishakhapatnam, Krishnapatnam, Chennai, Tuticorin and Cochin was the first dedicated service from South East India to Europe, and would see the first calls of mainline international shipping lines on ports in the east coast.

It is with this in mind that the acquisition of Krishnapatnam by Adani Ports is significant. Already the second largest private port in India and the largest in Andhra Pradesh, the Krishnapatnam port is the deepest port in the country with the largest waterfront area of 12.5 kilometres. It currently has the capacity to handle 1.2 million TEUs per year. An ongoing expansion will see its capacity increase to 2 million TEUs.

Adani Ports announced that it would acquire Krishnapatnam port from Hyderabad-based CVR Group in January 2020. With the company already commanding 30% of India’s container market, having handled 5.01 million TEUs in 2019 of the country’s total of 17.2 million TEUs, its share will increase with Krishnapatnam in its fold.

In addition, with Vizhinjam port in Kerala, which Adani Ports is developing as a “trans-shipment hub”, the company may control up to half of India’s container volumes, strengthening its already dominant position. In December 2019, Adani Ports announced that it intended to commence operations at the first phase of the port by December 2020.

Why Krishnapatnam is Crucial for Adani Group

The port, being acquired for Rs. 13,572 crore, is crucial for the Adani group in multiple ways. The two biggest commodities in terms of traffic at Krishnapatnam also happen to be important businesses for the larger Adani group.

Krishnapatnam supplies thermal coal to power plants and high-grade coking coal to steel plants in Karnataka, such as JSW Steel. (Adani’s Mormugao terminal in Goa vies for the same market). Coal forms about two-thirds of cargo traffic every year and one-third of its revenues.

Krishnapatnam is a major thermal power hub in Andhra Pradesh. In 2007, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government had proposed to make the region India’s largest power generation hub with a total capacity of 8,000 MW. Some 29 plants have been proposed in the region.

The port has an installed capacity of 5,490 MW. The Andhra Pradesh government is constructing another 800 MW plant, which would add to the coal traffic. It has a 12.5-kilometer conveyor belt to carry coal as well as mechanised coal handling infrastructure. Its biggest customer, accounting for one-tenth of total cargo traffic, is a 1,300-MW power plant owned by Singapore-based Sembcorp.

For Adani group, this represents a potential market for its coal mines in Indonesia and Australia. It might consider supplying its Australia coal to Krishnapatnam instead of Kattupalli Port, where protests by local fisherfolk have held up a key expansion.

In September 2019, India’s vice-president M Venkaiah Naidu inaugurated an electrified railway line connecting 112 kilometers from the port to the main rail route from Chennai to Kolkata, dedicated only to cargo movement. It was commissioned in June 2019 and completed in “record time”. The route even includes India’s longest electrified rail tunnel.

The new rail route would halve the time taken for cargo from the port to reach the main line, and bring down freight charges significantly – for coal, the freight cost per rate would fall by Rs 3 lakh to Rs 7.5 lakh, the chief railways official of the region has said.

Krishnapatnam is also an import hub for edible oil – the second important commodity the Adani group has stakes in. The refineries have a total capacity to process 7,200 tonnes of edible oils per day. That amounts to roughly one-fifth of India’s entire annual imports of edible oil. Port berths are connected directly to the refineries through dedicated pipelines.

Krishnapatnam has one of India’s biggest cluster of refineries, including those owned by Adani Wilmar, such as Krishnapatnam Oils and Fats, which it acquired in the 2012-13. All three top edible oil importers of India are customers of Krishnapatnam: Adani Wilmar, Emami Agrotech, Gemini Edible Oils.

Ecological Concerns

Krishnapatnam port has also raised ecological concerns, particularly beach erosion, which is common on the east coast. Strong wave action on the east coast lifts sand from one location and deposits it further along the coast. Predominantly, sand moves from south to the north. Building a hard structure on the coast, like a port, interrupts this movement. Sand begins to accumulate on the southern end of the structure while the northern coastline, deprived of fresh sand, begins to erode.

A study by the Ministry of Earth Sciences in 2009 found that the port was causing “severe” erosion of 30-35 meters per year over two kilometers of the coastline to its north. A 2015 biodiversity study of the area found “tremendous pollution pressure” on the port vicinity and threats to high coastal biodiversity in the region with 12 species of mangroves and nesting sites of the endangered Olive Ridley sea turtles.

Ironically, Adani has said that Krishnapatnam would help it create a “New Mundra” on the east coast – although in terms of container traffic and not the alleged threat to mangroves that dominated environmental litigation against the Mundra port.

The company expects the east coast traffic between Dhamra, Kattupalli and Krishnapatnam to cross 100 million tonnes per annum. It fills a “key gap” in the Adani Ports’s portfolio due to its “distinct serviceland which is presently not serviced” by the company, its presentation said.

Moreover, Krishnapatnam would also form a key link in the Adani group’s ‘string of pearls’ project to build ports along the Indian coastline and tap not just the cargo potential of each port but also the synergy from owning ports in all key locations in India.

An Adani Ports investor presentation acknowledges that Krishnapatnam will “complement the existing ports” of the group and, as an example, says that cargo can now move from its Dhamra port to Krishnapatnam, which is likely to be coal from mines in East India.

Karan Adani, CEO of Adani Ports (Gautam Adani’s elder son) said the acquisition would add “remarkable value” to its “pan-India footprint”. In describing the port, Adani described Krishnapatnam with a term used only for the Mundra port before; and for the first time, called the company’s strategy as borrowed from China’s strategic takeover of Asian maritime assets. “KPCL is a crown jewel to join APSEZ's string of pearls,” he said

Adaniâs âstring of pearlsâ of ports across Indiaâs coastline.

Adani Ports seeking regional presence

In April 2017, Adani Ports signed a memorandum of understanding to set up a container port at Carey Island in Malaysia. At the time, Karan Adani had said “Malaysia is very strategic to APSEZ global strategy and with straits of Malacca being a global shipping route it helps us to drive our global transhipment strategy further. With Vizhinjam port on one side Carey Island port on the other, we will be able to give trans-shipment solutions to global shipping lines.”

It took its first concrete step in the plan for regional expansion in May 2019, when Adani Ports announced that it had signed an agreement to develop and operate a container terminal at Yangon port in Myanmar.

These plans saw a significant boost when the COVID-19 pandemic rages in India. On May 28, Sri Lanka signed a deal with India and Japan to develop a deep sea container terminal. On July 23, Sri Lanka’s Information Minister Bandula Gunewardene announced that Sri Lanka was “continuing talks” with India over the development of the container terminal at the Colombo port. Adani Ports is reportedly a contender for the contract.

If this deal goes through, it would represent a delayed entry into the ports sector in Sri Lanka for the Adani group. In an interview to Newsclick in January, Rohan Abeywickrama, the CEO of SAR Shipping, a shipping company in Colombo, confirmed that Adani Ports had “looked into” the possibility of seeking to acquire for the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka, that ultimately went to a Chinese company in what was seen as a diplomatic defeat and geostrategic loss for India.

(To be continued)

With inputs from Ravi Nair and Paranjoy Guha Thakurta.

The writer is an independent journalist based in Mumbai. Additional reporting by Nihar Gokhale.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.