A Parade of Diverse Colours Against a Monochrome Nation

Two successive, harsh Delhi winters have seen the birth and replication of a significant paradox. This is what may be called a movement community. To call a movement a community seems a contradiction. A movement indicates mobility, while a community is presumed to be a settled habitation. The Shaheen Bagh agitation in Delhi last year against the CAA-NRC (Citizenship Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens) and the ongoing farmers encampment in Delhi highways against the three farm laws, are movements that have settled in specific places over long periods of time. The movements and the communities are co-terminus.

Movement communities may be seen as outgrowth of dharnas, the traditional mode of expressing dissatisfaction to authorities. The difference is thatthe dharna space is not a place to stay. It is an ascetic space that embodies the sacrifice of everyday life by protestors. Movement communities, on the other side,spin out their own life-worlds. These generate an ethic of bonding together with everyday practices and cultural productions that makes the inhospitable place of protest, a habitation.

At the centre is theshamiana(tent) where the main meeting is conducted. This is a place of seriousness where attentive faces go to listen to the “baat” (views) of organisers and guest speakers, many of whom are ordinary citizens. In farmer’s protest sites, participants are scattered in different tractor-tents, some with their women-folk, others with friends and relatives, chatting or cooking or making tea, washing clothes, sweeping the place, strolling across to the border.

This is a physically bonded political community that has different relationships with existing organisations. The Shaheen Bagh agitation is remarkable for being kick-started by women, especially elderly “dadis” (grandmothers). It remained famously “leaderless” as the Delhi Police found to their bemusement. The farmers’ agitation is co-ordinated by the SamyuktKisan Morcha, a collection of over 40 farmer organisations. This functions on the principle of general assemblies with voting, in procedures that allow for the pressure of the ordinary farmer participants to be exerted on them. The visibility of the leadership is far less than the diversity of the community. It ranges from the Nihangs (Sikh warrior order), with their distinctive blue robes andtalwars(swords) peacefully drinking tea, while the presence of the Left is visible in pavement bookstalls.

The self-organisation in movement communities spring from an existential determination. Underlying the demand for the repeal of the three farm laws is the anxiety that farming lands will be taken away in the course of unequal transactions with corporations. The Shaheen Bagh movement sprang from the immediate threat of deportation and second-grade citizenship. Together with the determination to save their existence, is a commitment to peace. The ethic of peace necessarily involves self-restraint, especially in the atmosphere of vilification and threat of merciless repression produced by governmental and vigilante agencies.

A key element of the movement community is food. Organisedlangars(community kitchens) are well-publicised, but there are also groups of men in different tractor-tents who cook together and offer meals to outsiders quite spontaneously. Equally important is the commensality between religious communities. In Singhu, a Muslim organisation offerslangarto participants. Besides thejatha(contingent) from Punjab which opened alangarat Shaheen Bagh, there is the remarkable story of a Hindu housewife in journalist Seema Mustafa’s edited volume. Outraged by attacks on university students, she became a regular attendee at Shaheen Bagh, dining and staying over at Muslim households.

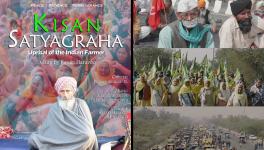

The Shaheen Bagh movement was propelled by Muslim women; the farmer’s agitation is prominently Sikh. But both produce a broad political culture. These movements are not averse to using social media, but do not rely on its virtuality. Both movements generate the richness of their cultural content in the spaces they occupy. The cultural productions of the Shaheen Bagh movement included colourful cut-outs, murals done on roads and walls together with calligraphed tea cups freely gifted by Jamia Millia Islamia students.

The farmers’ agitation lacks a supportive neighbourhood but it compensates by handwritten posters strung on individual tractor-tents. Equally interesting are the books. A mobile library was set up in Shaheeh Bagh itself; a touching sight is a library run by a Singhu farmer consisting of a trayful of books. Social media circulates the physical cultural productions and events of these communities, reaching out to new social constituencies, especially youngsters who visit and stay on to contribute creatively or organisationally to the community.

The ability to generalise their appeal has an underlying reason. It lies in their claim to the national flag and the Constitution. In post-Independence India, nationalism has been propagated by the State or by political parties. The movement communities of today indicate the beginnings of a new nationalism from below. Both movement communities prominently display the tricolour as a way of claiming their rights – and, in that process, broadening their appeal to other sections of the country.

The tractor rallies planned for the Republic Day is a remarkable improvisation. For the first time in the history of this country, there will be a counter-Republic Day parade, possibly with each state being represented separately in the rally. This is not just a show of force. The visual significance of it is one that is designed to show what is really happening to the social world of the Republic. Above all, this demonstrates the importance of protest, dissent and people’s mobilisation as a foundational principle of the Republic itself.

Movement communities have come at a time when Hindu populism has introduced a new culture of governance based on a triple circle. A concentrated circle of power in a sovereign-like leader together with concentration of wealth in favoured monopoly houses; underlying these, a concentration of power to decide what counts as legitimate religious practices of the nation.

Socially, Hindu populism has bound the nation by its antagonistic relationship with those it defines as non-Hindus. Movement communities have forefronted the importance of multiple religions coming together on the same platform. Both Shaheen Bagh and the farmers' protests have hosted religious leaders of different communities in either joint meetings or separately as speakers.

It may be argued that movement communities are not stable and being movements have no lasting power. This is self-definitionally true. A movement is an exceptional time and hence cannot become stable and permanent. But what movement communities possess is an enormous public impact. A comparable instance is the Rizwanur movement in Kolkata in 2007 which was a prolonged campaign against the murder of the partner in an interfaith marriage. It was centred around a sacred spot on the pavement next to St Xavier’s College where the murdered person had studied and amplified by the social media. As a movement it slowly melted away but it caused a tremendous crisis of trust and legitimation in the ruling government. At a global level, the Occupy Wall Street movement mobilised an enormous critical and oppositional energy against the neo-liberal, hyper concentration of wealth.

The Shaheen Bagh and farmer’s protest, too, have not found a stable institutional form. But the very nature and form of the movements themselves promise an open and youthful political culture that values specific identities while open to their inter-relationships. Against a charismatic leader, an open political community; against the concentration of wealth, the claim to rights; against a monochromatic nation, the stitching of the tricolour from mobilisations of different social groups. Most of all, it underlines the need for a stable political community, the members of which can equally regard the nation as its home.

The writer is a former professor of political thought, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.