Why is India Failing to Provide Quality Education to All?

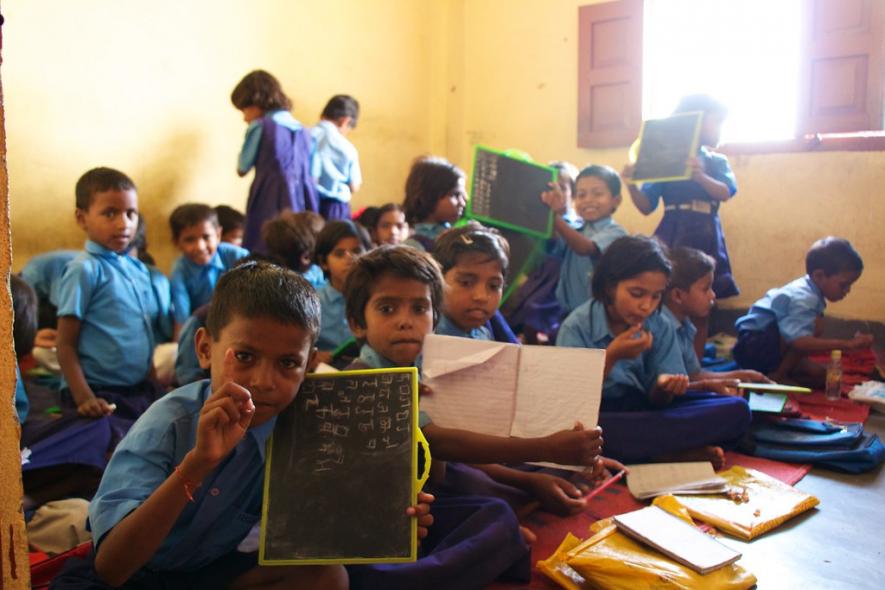

Representational Image. Image Courtesy: Flickr

ASER (Annual Status of Education Report) has been raising concern for the quality of education ever since they started assessing the status of children's enrolment and learning outcomes in rural India in 2005.

The first report highlighted an urgent need to improve the foundations of basic reading and arithmetic in the early grades of school, as a strong beginning is essential for building a solid foundation. In 2017, they focused on the 14-18 age group in their 'beyond-the basic' report. Revisiting the same age group in 2023, six years later, reveals the continuation of the same weak foundation among the youth ready to join the workforce.

ASER's 2023 report once again rings the alarm. The survey results show that only 73.6% of youth aged 14-18 can read at least standard II-level text. 45% exhibit basic proficiency in arithmetic, while the remainder must make up ground. There is no need to point out that a weak foundation ultimately culminates into poor employability.

Education is the first and the foremost input for human development. It is the foundation for realising the full potential of the demographic dividend on the route to a developed nation. For policymakers, it is an important tool to integrate the masses in the development process and accelerate the development process as it empowers people, encourages critical thinking, and cultivates a society capable of using its demographic advantage for collective growth and prosperity, all based on philosophical ideals of enlightenment and empowerment.

For individuals, education is supposed to improve their skills and consequently provide better employment opportunities, a chance that every individual looks forward to improve their lives. In that sense, it is a basic tool for millions of people to improve their social and economic status. It gives hope to break the shackles of ignorance and poverty.

So, a benevolent government is expected to prioritise education to support the masses in overcoming deeply rooted societal discrimination. Then why is it that we, collectively as a society and a state, are continually failing to establish a system that ensures good quality education for all? Why is the education that is supposed to facilitate a level playing field for all widening the gap?

In a market economy, supply responds to the demand pressures. In the case of education, demand emerges from two important sources. One, students and their parents and two, the employment providers. For many in the rural area, this is the first generation to reach secondary education. For them, any education is good education. They do not have the privilege to question the quality of education and its futility. Because of this demand, the number of schools and colleges has increased, and the enrolment rate has improved significantly.

Productive economic activities require good skills for efficient production. However, the demand for skilled labour is not increasing at the same pace as that of the supply of the skills. Unemployment among educated youth has remained a perennial problem.

India faces a paradoxical situation where the unemployment rate rises with the increase in the education level. As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey of 2022, the unemployment rate for non-literate and literate and up to primary was 0.4% and 1%, respectively, whereas the unemployment rate among individuals with secondary education and above was 8.6%, the highest among other levels of education.

Two sets of reasons can explain this paradox. On one hand, not all of the educated workforce is employable. Only 45% of the graduates were found employable, as per the report published by Mercer Mettl (Economic Times – August 1, 2023). The Bloomberg report in April 2023 also pointed out that Indian youth graduating from India's $117 billion education industry have very limited or no skills.

On the other side, the country's economic growth has remained labour-saving, as indicated by many researchers. That means the economic growth is not generating adequate employment opportunities. The need for quality skills is getting fulfilled, leaving a large surplus workforce. As a result, we see not only brain drain but also a noticeable 'Dunki' phenomenon.

Our observations from working in the higher education sector suggest that a large number of jobs generated in the economy are not in tune with the skills that their respective degrees represent. In short, a pressing demand is not emerging from the productive sector that can compel policymakers to take quick actions towards reforming the education sector to ensure quality education for all. So, the government must take up the cause.

India's education sector is a formidable economic contributor, currently commanding an estimated value of around $117 billion. Projections point toward substantial growth, with expectations reaching $225 billion by 2025. However, despite the expanding educational landscape and the pursuit of higher education degrees and qualifications, a significant number of individuals in India find themselves grappling with challenges in securing employment. This paradox raises critical questions about the alignment between the supply of an educated workforce and their demands in the job market.

As the sector continues to burgeon, addressing the employment gap for educated individuals becomes imperative to harness the full potential of India's educational investment and ensure meaningful contributions to the workforce.

Neha Shah is an Associate Professor of Economics, LJ University, Ahmedabad. Atman Shah is an Assistant Professor of Economics, St. Xavier's College (Autonomous), Ahmedabad. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.