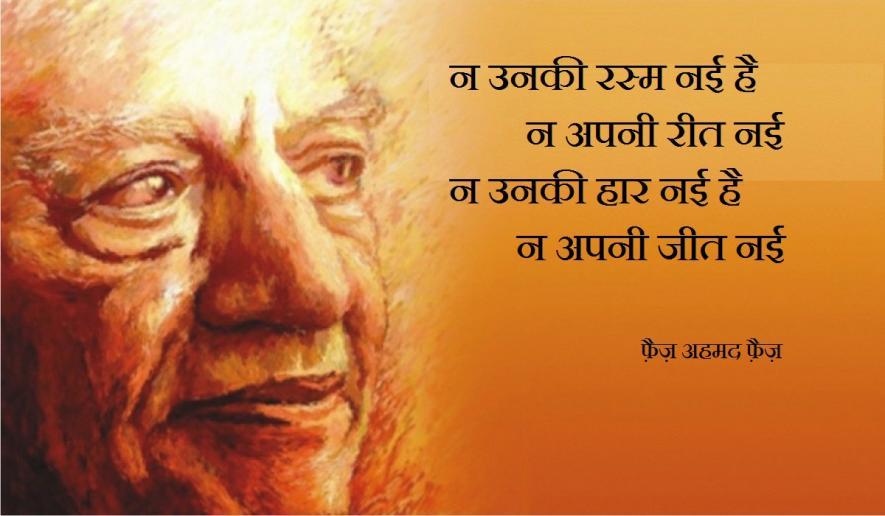

The Stairway of Faiz’s Poetry

Well into the 21st century, reading Faiz Ahmed Faiz is like reading a living poet. Faiz is simple, deceptively simple, and profoundly complex. When he was little, the first poets he read were Ameer Minai and Daagh Dehlvi. To many of us living today, Faiz is our first poet. The first poem that I remember learning by heart is Faiz’s Tum Apni Karni Kar Guzro (Do What You Must). Even as one grows up and the indulgence of the mind demands greater depths and abstractions, Faiz does not move away. It’s like he has built a long stairway of poetry for people to walk.

Each poet builds their stairway of poetry. Across the stairway, there are floors (or levels) of their poetry. What are these floors? These can be forms of poetry; its traditions; themes; ideology; imageries; motifs; symbols; dexterity of language and whatever you may. The specificities of these floors may differ, but the stairway of poetry must lead toward a high point of universalism, without which the stairway only has a foundation at the bottom but it leads to nowhere.

A poet might attain expertise in all forms of poetry, but their lack of depth might not stand the test of times. A poet might be a revolutionary, but their poetry might die with the revolutionary fervour, and a new revolution might demand a new kind of poetry. They might be dexterous at language, but the structure of the language itself might change to make them obsolete.

In the long run, neither the number of floors in the stairway of poetry matter, nor the lifetime fame of a poet, nor the poet’s personal lore. Poets who were buried unknown have been discovered centuries later. Poets who were at the peak of fame in their lifetime are now as forgettable as the last mistake one makes.

Only poetry that reaches the high point of universalism can survive the test of time, even if the poet wrote only in one form, in one meter and in one language all their life. The cosmic force of universalism is birthed through the creationary foundation of love. If this notion of love can manifest in a poet’s pen, their verses will stand the test of times.

A poet must write to the extent that he is able to feel, said Faiz in an interview with – then young – Ahmed Faraz and Iftikhar Arif. He must insert his politics to the extent that he believes in it. He must write from the heart and not for any other reason, he said.

Hum Pravarish e Lauh o Qalam Karte Rahenge

Jo Dil Pe Guzarti Hai Raqam Karte Rahenge

We’ll keep nurturing the tradition of the Pen and Slate

We will keep writing of the heart and its State

Faiz’s personal lore is arguably as big as his poetry, further bejewelled by numerous hypnotic musical renditions of his nazms and ghazals by the musical greats of the Indian sub-continent. Firaq Gorakhpuri once said that every great poet needs to be bigger than his poetry (Har Badey Shayar ko apni shayari se mawara hona chaahiye). Faiz might be considered bigger than his poetry, and the temptation to assert that he is as big as he is because of his personality, is strong. His revolutionary ideal adds another layer to this temptation.

But, even if Faiz’s personal saga was not as big as it was, his poetry would still be just as big.

When Faiz began writing, Urdu poetry was not short of stalwarts. Iqbal had already cemented himself as arguably the greatest of his time, weaving every theme into the mould of ghazal. Beyond Iqbal, poets like Maulana Hasrat Mohani had a huge following among the youth. Firaq was already exploring unchartered territories which would later give way to modernism in Urdu poetry. Jigar (Moradabadi) was mesmerisingly big. Josh (Malihabadi) was becoming the poet of revolution.

Faiz’s poetry rose with the rise of the Progressive Writer’s Movement, whose foundation was laid by Sajjad Zaheer and Mulk Raj Anand, and the first convention was presided over by (Munshi) Premchand in Lucknow in 1936. With time, people like Faiz, Majaz (Lakhnavi), Ismat Chugtai, Ali Sardar Jafri, Jazbi (Moin Ahsan), Sahir (Ludhianvi), Jaan Nisar Akhtar, Kaifi Azmi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Makhdoom (Mohiuddin) and many others joined the movement.

The structure of Faiz’s poetry, his metaphors, were not unique to him but were the common product of the movement. Faiz’s greatness lies in his evolutionary poetry, a term I have borrowed from Professor Gopichand Narang’s analysis of “Evolutionary Love.”

The first level of Faiz’s poetry is where he is transparent. He sprinkles the symbolism of the classical tradition of Urdu and Persian, along with imageries of the English poets, to weave a beautiful clothing of words but the thematic boundary remains singular, or, if there are multiple themes, the demarcation points can be easily traced.

Raat Yu’n Dil Mein Teri Khoyi Hui Yaad Aayi

Jaise Veeraney Mein Chupkey se Bahaar aa Jaaye

Jaise sahraao’n mein hauley se chaley baad-e-naseem

Jaise beemar ko be-waj’ha qaraar aa Jaaye

Last night your faded memory came to me

As in the wilderness spring comes quietly

As, slowly, in the desert moves breeze

As to a sick man, without cause, comes peace

Very ably translated by another great, Vikram Seth, the poem is the opening Qata from Faiz’s first published collection, Naqsh e Fariyadi. The first half of Naqsh e Fariyadi is filled with many similar examples. Here’s an excerpt from a poem in Dast e Saba; Mere Humdum Mere Dost (My Companion, My Friend)

…gar mujhey iska yaqee’n ho merey humdum mere dost,

roz o shab, shaam o Sahar main tujhey behlaata rahoo’n,

Mai tujhey geet sunaata rahoon halkey, shiirii’n

aabshaaron ke bahaaron ke chamanzaaron ke geet

aamad e subh’a ke, mehtaab ke, sayyaron ke geet…

…If I am sure of this my companion, my friend,

I would be your muse night and day

I would sing sweet, gentle songs for you

songs of waterfalls, the spring and gardens

of morning, of the moon and the beautiful planets…

Or, the following couplets from some of his ghazals,

Hui hai hazrat e naaseh se guftagoo jis shab

Wo shab zaroor sar e koo e yaar guzri hai

Wo baat saare fasaaney mein jiska zikr na tha

wo baat unko bahot na-gawaar guzri hai

Each night whereby I spoke with the respectable priest,

I spent roaming around the lanes of the beloved

That thing which never even came up in the story,

has hurt them the most.

…

Mohtashib ki khair, uncha hai usi ke Faiz se

rind ka, saqi ka, mai ka, khum ka, paimaaney ka naam

Faiz unko hai taqaza e wafa humsey jinhein

aashna ke naam se pyara hai begaaney ka naam

Long live the censurer, for it is he who grants prestige

To the name of drunkard, the wine, the vineyard, and the goblet

Faiz, even they expect loyalty from me

Who would favour a stranger over their friends

…

Dil mein ab yu’n tere bhooley hue gham aate hain

jaise bichdey hue kaabe mein sanam aate hain

Your forgotten sorrows greet my heart

like the estranged idols of Ka’ba return to greet their former home

…

Ab wahi harf e junoo’n sab ki zabaa’n thehri hai

Jo bhi chal nikli hai wo baat kahaa’n thehri hai

Dast e Sayyad bhi aajiz hai, kaf e gulchee’n bhi

bu-e-gul thehri na bulbul ki zabaa’n thehri hai

The same Euphoria rests on everyone’s tongues now

What can stop something when it has the momentum?

Hands of the hunter, Grip of the Flower Picker are useless

Neither the fragrance of the flower, nor the nightingale’s song can be stopped

….

At level one, Faiz is distinguishable from his contemporaries not in his themes and ideology, but only in his style, tone, and emotion. He is a poet of revolution but he does not rage through. He summons the most powerful binder of all revolutionary spirits, which is not rage but pain. Pain is universal. It is the manifestation of the creationary force of love inside the human conscience. For instance, Faiz writes ‘a lullaby for the Palestinian Children.’ He writes a song, ‘Africa Come Back.’ He writes an elegy for the Iranian students who lost their lives during the early years of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. He writes songs for the working class. But in all these themes and writings, he is not a unique entity. All these inspirations can be found in other progressive writers of the time. Yet, for example, when Faiz pens Sub’h-e-Azaadi (Morning of Independence, 1947), he is distinguishable in his emotion and tone from others.

Between Level 1 and Level 2, there is a connecting stop. Three of his famous poems represent this stop: Mujhsey Pehli Si Mohabbat, Raqiib Se! and Do Ishq. These poems represent a turning point guided by an inner conflict – between personal and social love. The inner conflict of the poet does not let the two realms merge seamlessly. Not yet. Each poem consists of individual sections which can be clearly differentiated. The initial section in each of these poems is about the personal nostalgia of a personal love that was. Then, the shock of the present wakes the conscience of the poet of the East toward a far greater force of love which is rooted in social emancipation.

From here, Faiz must reach level two, along with the rest of the Progressives. Instead of fevicoling the personal and the social, he must evolve to integrate the two realms of love. If it is possible to imagine a world where personal love is not the enemy of social responsibility, then it should be possible to resolve this conflict within poetry as well. And Faiz manages to reach it, along with the whole of Progressive Writers’ Movement.

The classical Urdu metaphors are moulded into newer meanings of the socialist ideals. Raqiib or the rival in love, is no more the individual but the oppressive system of capitalism and imperialism. The aashiq, the lover, must struggle against the Raqiib to win back the beloved (emancipation of the people). Ishq, vasl, hijr (Love, Union, Separation); rind, maikhana, bulbul, gul, Naaseh, Mohtasib, Haakim (Drunkard, Tavern, Nightingale, Flower, Advisor, Censurer, Ruler) all these characters or metaphors transform into powerful poetry of revolution.

Remember, Faiz does not do this alone, and even at this level, he is distinguishable majorly in his style, tone and emotion, in addition to his symbolism which is honed to a great degree now. His lyrical mastery attains new heights. In a poem like Aaj Bazaar Mein Pa-Ba-Jaula’n Chalo (Today, Walk the Bazaar in Chains) he can effortlessly evoke tears with Raah Takta Hai Sab Shehr-e-Jaana’n Chalo (Keep walking, for the city of the beloved awaits you).

Hum Par tumhaari chaah ka ilzaam hi to hai

Dushnaam to nahi hai ye ikraam hi to hai

Dil na-umeed nahi na-kaam hi to hai

Lambi hai gham ki shaam magar shaam hi to hai

I am only accused of loving you, so what?

It is not a curse but an honour, so what?

The heart has only failed, it is not without hope

If the evening of despair is long, so what?

…

Gulon mein rang bharey baad-e-nau-bahaar chaley

Chaley bhi aao ke Gulshan ka kaar-o-baar chaley

Maqaam Faiz koi raah mein jacha hi nahi

Jo koo-e-yaar se nikley to soo-e-daar chaley

Let the morning breeze colour the flowers vibrantly

Return, my love, for whom else will the garden bloom?

No stoppage suited me, Faiz

From the abode of the beloved, I only walked toward the gallows

…

Kahaan hai manzil e raah-e-tamanna hum bhi dekhenge

Ye shab hum par bhi guzregi ye farda hum bhi dekhenge

We will see the destiny of the road of yearning

We will witness this night and the morning that will greet us after

…

Qarz e nigaah e yaar ada kar chuke hain hum

Sab kuch nisaar e raah e wafa kar chuke hain hum

I have repaid the debt of their loving glance

I have sacrificed everything to the journey of loyalty

…

Is ishq na us ishq pe naadim hai magar dil

Har daagh hai is dil pa’ ba-juz daagh-e-nadaamat

I am not ashamed of this love or that love

My heart carries every would, except that of guilt

…

At this level, Faiz is as masterful as anyone. But to see his universalism, we must present a stronger case, and we must climb up to level three, the transcendental level. Here, Faiz is surrounded by his castle of timeless nazms. In his own words, Faiz found ghazals to be limiting. Once you attain mastery of ghazals, he opined in a BBC interview, it becomes an easy job to write the next ghazal and hence it limits the expressive capabilities of the form itself.

However, in the same interview, Faiz praised Iqbal for proving that even the most difficult political topics can be woven into ghazals, provided the language of the ghazals adheres to its roots. Why then did Faiz not write ghazals as prolifically as he wrote nazms? This is a point which divides critics.

Factually, Faiz does not have the number of overall as well as flagship ghazals as the greats of the Urdu poetry. His contemporaries like Majaz, Majrooh, Sahil, Kaifi were all excelling in ghazals. There were writing prolifically. Some prominent critics, including Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, did not consider Faiz to be a great poet. Very technically, a shayar is someone who can compose a quality sher (Couplet) consistently. Faiz does not have a lot of couplets in his entire cannon. And if we keep only the best among those, the number reduces to much lower.

The arena in which Faiz excels beyond competition is the arena of free poetry, or nazm. Whether Faiz did not pay attention to ghazals or could not excel at them is irrelevant to Faiz’s universalism because he managed to push the boundaries of free poetry to unprecedented vastness. This is where Faiz can put into words a sort of fourth dimension, guided by the recognition of the all-encompassing force of love. This is the space which subsumes ideology, rage, emancipation, confinement, loneliness, social awakening and all other things.

All great poets have managed to evoke universalism in their expression. Faiz might only occasionally reach this point in his ghazals, but he charges into it in his nazms. Let us see some excerpts:

Mauzoo-e-Sukhan

(The Object of All Speech)

Gul hui jaati hai afsurda sulagti hui shaam

Dhul ke niklegi abhi chashma e mehtaab se raat

Aur mushtaaq nigaahon ki suni jaayegi

Aur un haathon se mas hongey ye tarsey hue haath

Un ka aanchal hai, ke ruskhsaar, ke pairaahan hai

Kuch to hai jis se hui jaati hai chilman ranngi’n

…

Ye bhi hain, aise kayi aur bhi mazmoo’n hongey

Lekin us shokh ke aahista se khulte hue honth

Haaye us jism ke kambakht dil-aawez khutoot

aap hi kahiye Kahin aise bhi afsoo’n hongey

Apna mauzoo-e-sukhan inkey siva aur nahi

tab-e-shayar ka watan inkey siva aur nahi

The flame of evening is dimming

From the fountain of moon, the night will descend

And it would hear the pleas of awaiting eyes

And take our longing hands into hers

Is it her lap, her soft cheek, her fragrant cloth?

what grants colour to this veil?

…

There shall be other subjects to speak of

But the slow parting of those lips

And to witness the outlines of her bewitching form

Tell me, is there any other magic so powerful?

The is the subject of poetry

This is the homeland of the poet

This and nothing else

…

Zindaa’n ki ek shaam

(Of a Night in Jail)

Shaam ke pech-o-kham sitaaron se

zeena zeena utar rahi hai raat

…

Dil se paiham khayal kehta hai

Itni shiiri’n hai Zindagi is pal

Zulm ka zehr gholne waley

Kaamra’n ho sakenge aaj na kal

Jalwa gaah e visaal ki sham’en

Wo bujha bhi chukey agar to kya?

chaand ko gul karein to mai jaanun

From the webs of evening

Step by step, the night comes down

…

The thoughts continuously implore the heart

Life at this moment is so sweet

Those who want to mix the poison of oppression in this life

Will not be successful today or tomorrow

So what if they have extinguished

the candles of the land of union

Can they ever extinguish the moon?

…

Zindaa’n ki ek Subha

(Of a Morning in Jail)

Raat baaqi thi abhi jab sar e baalii’n aakar

Chaand ne mujhse kaha…”Jaag Sahar aayi hai..”

…

Chaand ke haath se taaron ke kanval gir gir kar

Doobtey, tairtey, murjhaatey rahe, khilte rahe

raat aur sub’ha bahot der galey milte rahe

The night had still not crept away when, in my ears

The moon whispered, “wake up and see, morning’s here”

…

From the hands of the moon, stars fell like petals

They drowned, swam, dried and blossomed again

Departing night and the ascending day, hugged for long

…

Manzar

(Sight)

Rah guzar, saaye, shajar, manzil o dar, halqa e baam

Baam par siina e mehtaab khula aahista

Jis tarah kholey koi band e qaba aahista

Halqa e baam taley saayon ka thahra hua niil

niil ki jhiil

Jhiil me chupkey se taira kisi patte ka habaab

Ek pal taira chala phoot gaya aahista

Bahot aahista bahot halka khunak rang-e-sharaab

mere shiishey me dhala aahista

shisha o jaam suraahi terey haathon ke gulaab

Jis tarah door kisi khwaab ka naqsh

aap hi aap bana aur mitaa aahista

Dil ne dohraya koi harf e vafa aahista

tum ne kha, “aahista!”

Chaand se jhuk ke kaha:

“aur zara aahista”

The path, the shade, the trees, the steps and door, the rooftop

The bosom of the moon opened over the roof, slowly.

Like someone unhooks their cloth, slowly

Near the rooftop, the still shadows which were blue

like a blue lake

In that lake, a leaf swims to form a bubble

Swam for a moment, and then burst, slowly,

Very slowly, very lightly, the colour of the wine

Poured itself into my glass, slowly.

the goblet and the jug, your rosy hands?

Like the image of a distant dream

extinguishes itself, slowly.

The heart repeated a loyal word, slowly

You said, “slowly”

The moon bowed and said:

“More slowly still.”

…

Numerous other examples can be quoted and the list will not end. At the highest level, Faiz only speaks in metaphors. The night is his favourite setting. Pain is his favourite catalyst. Solitude is his canvas. Moonlight is his favourite metaphor for hope in the dark night. The crescendo goes toward a heightened sensation of pain and despair; and then a toward a resolve of living through to see the morning light. But even if that crescendo isn’t built, the moonlight itself is the most charming metaphor of all of Faiz’s poetry. He has utilised moonlight so much that it seems second nature to anyone reading Faiz.

These writings, seem to be set in a cosmic space where entities flow with a magical fluidity. This imagery is not accidental. Faiz does not accidentally tread into this magical realism once or twice. Rather, his poetry evolves to reach this point.

In a poem titled "Ai Habeeb e Ambar-Dast” Faiz quotes a couplet from Hafez. He quotes the same couplet to end his acceptance speech for the Lenin Peace prize.

The couplet is:

Khalal Paziir buvad har bina ke mai-biini

Ba-juz bina e Mohabbat ki khaali az khalal-ast

-Hafez

Every foundation can be and is distorted by something - another foundation.

Except the foundation of love which is beyond these distortions

Hafez asserts that love is that foundation which is beyond distortions. Faiz quotes Hafez twice. Faiz inherits this idea from Hafez and in all his poetry which tugs at our heartstrings. This overwhelming, distortion free force of love is the force of revolution, the keeper of hope, the comforter of solitude, the companion during separation, the driver toward union, so on and so forth. That Faiz’s poetry can take us to the depths of despair and then pull us back just at the right moment is not an accident. It is the evolution of his poetry.

This love is the melting pot for all themes. And the best example from all of Faiz’s cannon of this melting pot is his evergreen nazm, Hum Dekhenge!

All the world is his canvas when he begins with Hum Dekhenge (We shall witness). Immediately, powers outside of the earth are called into action – lightening, desolation of the mountains (like cotton plants fly away); the eternal slate (lauh-e-azal) of truth. The vantage point in all this is undeniably, love. Only from this vantage point can a poet speak of absolute justice, which leaves not an iota of remaining injustice after its wrath is unleashed.

‘Sab taaj uchaaley jaayenge.

Sab takht giraaye jaayenge’

Every Crown shall be tossed. Every throne shall be destroyed.

And then, in the final stanza, only the cosmic love remains. Bas Naam Rahega Allah Ka. Only Allah (truth) will remain. What is a name but an attribute or ideal through which we approach God? And what is God?

Jo Ghayab Bhi hai Haazir Bhi

Jo manzar bhi hai naazir bhi

That which is absent and present

That which is the sight and the beholder.

Faiz invokes the most elaborate religious philosophies of the Vedanta and subsequently of the Sufis, of the infinite force of creation, of the finite world which we exist in.

And then, when only the cosmic love remains, it also asserts itself as the only truth and now, the awakened masses of the world can declare (We are truth – Utthega an’al haq ka naara).

How could Faiz, a committed socialist, pen down a plethora of invocations if he had been tied down to a singular inspiration? A poem like Hum Dekhenge, which is an evergreen example of poetic mastery and revolutionary spirit, can only be written from the high point of Hafez’s notion of love.

I believe beyond doubt, that Faiz will remain fresh for as long as Urdu is spoken. I can only think of closing this essay with an excerpt from Prof Gopichand Narang’s impassionate introduction of Faiz in his last televised Mushaira.

“…Urdu poetry cannot take enough pride in a poet like Faiz sahab…. He is a poet of revolution, but his tone is content, his voice soft and breezy which tugs at our heartstrings. He possesses an ability to comfort the ailing heart, like someone keeps their soft hands on your heart’s cheeks…”

The writer is a data analyst by profession and a student of literature by inclination. The views are personal. alyasa.abbas@gmail.com

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.