Looking at Cuba’s Revolution 61 Years On

Image Courtesy: teleSur English

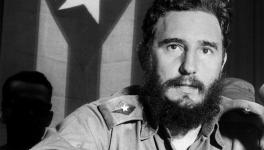

In the popular imagination, the Cuban revolution that took place 61 years ago was as a heroic act of a group of guerrilla fighters led by the charismatic Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. This perception does not do full justice to the many internal complexities of the revolution. It is also perceived as the overthrow of a dictator by a group of young adventurers, inspired by the rich tradition of armed struggle against Spanish colonialism in the19th century. Therefore, this revolution is often categorised as a mere subset of communist revolutions. In doing so, some of its unique features are papered over.

Because of its association with guerrilla warfare and the immense popularity of Che Guevara, the Cuban revolution is often romanticised at the cost of its intricacies. Indeed there is much to fuel the romantic imagery of those days: the young heavily-bearded revolutionaries or barbudos, the failed attack on the Moncada barracks on 26 July 1953, the arrest of lawyer-turned-rebel leader, Castro himself.

Castro prepared his historic four-hour “history will absolve me” speech in prison, and it became the manifesto of the 26 July Movement. The romantic imagery of the Cuban revolution owes itself also to the series of events and how they unfolded: the historic landing of the shabby wooden ship, nicknamed Granma, which was carrying 82 rebels from a safe house in Mexico to a small Cuban Island in the rain and storm; the escape of the Castro brothers, Camilo Cienfuegos and Guevara, starved and exhausted, and the few others who escaped with them but ran into government patrols and spotter planes the moment they crashed on the swamps of Oriente province.

But the Cuban revolution, which reshaped the political landscape of Latin America and pushed the world to the brink of nuclear war, as exemplified by the Cuban Missile Crisis, is much more than two years of guerilla warfare. After the death of Castro, its paramount leader, in 2006, academicians and scholars have attempted to trace how a socialist government came to be established on this tiny island nation in the Caribbean sea.

Essentially, what we call the Cuban revolution began as a multi-class, anti-dictatorship political movement that later transformed into a socialist revolution. Perhaps the Cuban Socialist revolution is the only one in history not initially led by a communist party leader with a well-defined program. The Communist Party of Cuba, which is in power today, was formed in 1965, six years after the revolution. The political movement transitioned into a social revolution after the attack on Moncada barracks on 26 July 1953, which we know as the 26 July Movement.

The movement began with a group of unemployed youth, industrial and farm workers led by Castro, who decided to undertake an armed struggle after his failed attempt to challenge the constitutionality of then president Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship in Cuban Courts. The revolution then unfolded in two phases.

The first was the insurrection, in which the peasants played the primary role, along with intellectuals and a few student groups. The political economy context of the time was the growing imperialistic influence of the United States, especially over the backbone of the Cuban economy at the time, the sugar industry. The brutal rule of Batista along with comparatively slower economic growth led to unemployment and widened the gap between the rich and the poor. These were the prime reasons for growing popular discontent among a significant section of Cubans.

The second phase began after the dictatorship was overthrown and it was enmeshed within the politics of the Cold War. This phase was far more complex compared to the insurrection phase.

Earlier, Castro had tried to keep himself and his movement at a distance from communism. His alliance with the Popular Party of Cuba (the Communist Party of Cuba before 1944) was motivated by the party’s organisational strengths. But during the second phase, Castro slowly and steadily began to move towards Marxism-Leninism.

Analysts now say that before the victory Castro never claimed to be a Marxist, though two members of his group, Raul, his brother, and Guevara, were avowed and vocal communists.

In the insurrection phase, alliances had been formed with different groups in the context of fighting Batista’s forces rather than on the basis of concrete ideological considerations. But in the second phase, the revolution became more complex as the attention turned to the future of a country that had for a very long time been dominated by American economic and political imperialism.

The course the Cuban revolution took under Castro was influenced by the socio-economic and political developments since the country’s independence from Spain and the continuous US intervention in Cuban politics during Batista’s dictatorship. In an article he wrote in 1963 for the New Left Review, British historian Robin Blackburn provides rich empirical data on the structure of Cuban society in the immediate post-revolution phase. According to him, there were around 4,00,000 highly-unorganised urban proletariat, 2,50,000 petit bourgeoisie, around 5,70,000 rural workers, a peasantry of 2,50,000. The largest category was of the unemployed, around 7,00,000 who lived in shanty towns.

After becoming prime minister, Castro took on a massive program of nationalising industries, education and health. He instituted agrarian reform, including land programs that directly benefited 2,00,000 peasants. He raised the pay of petit bourgeoisie officials at the expense of higher-ranked officials. As a large chunk of the land and factories were controlled by US capital, and the nationalisation project was seen as ‘socialist’, the infant revolutionary socialist state garnered US ire. This manifested in the infamous Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961.

The second post-revolutionary phase of the revolution was influenced by Castro’s leadership skills. This phase allowed his brilliant statesmanship to rise to the fore. Castro started a project to bring together various influential forces in Cuba, which led to the Integrated Revolutionary Organisation or ORI in 1961. It comprised of the Castro-led 26 July Movement, the Popular Socialist Party and the initially anti-communist Student Revolutionary Directorate led by Faure Chomon. In 1962, the ORI become the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution, which in 1965 became the Communist Party of Cuba.

In this way, the history and development of the Cuban ruling party of today are deeply influenced by the course of the Cuban revolution.

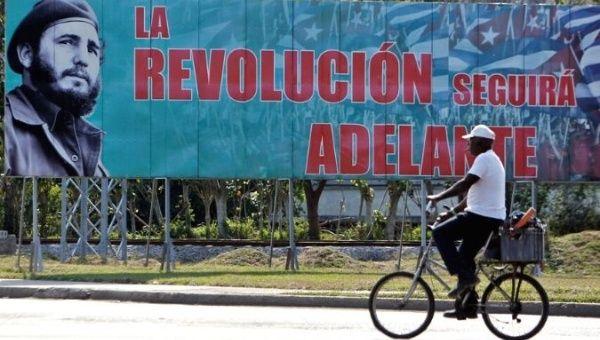

Sixty one years on, the Cuban revolution has survived the Cold War, the fall of the Communist bloc and severe embargos by the United States. Cuba is the only one of four socialist states modelled on the principles of Marxism-Leninism. The Cuban revolution and its leaders have inspired people and movements around the world and continue to do so.

The author is a research scholar at JNU. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.