Law Commission Says No to Death: Inches Towards Life

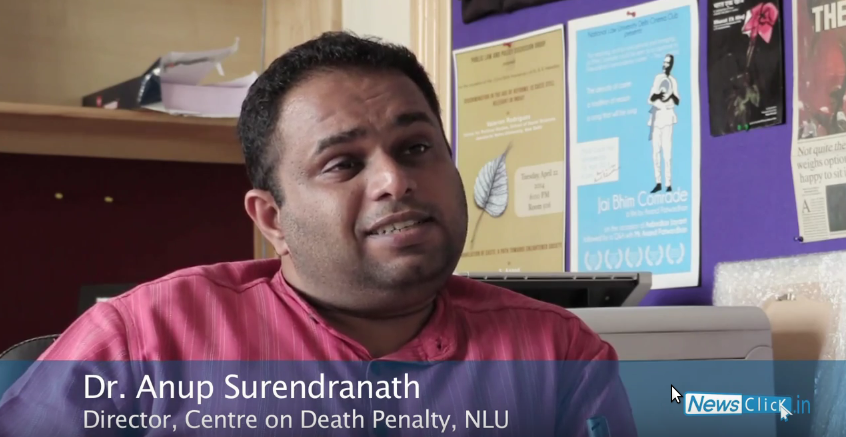

Newsclick interviewed Anup Surendranath, Director, Centre on Death Penalty, NLU on the Law Commission report which has recommended that the country should move towards abolishing death penalty. Anup called it a landmark move but also raised questions over the reason given by Law Commission for keeping the death penalty applicable in terror cases. He also pointed out that the ‘rare of the rarest’ clause is not systematically followed in most of the lower courts where judgment is more based on emotional stands of the judges. Anup further explained that the judicial processes are usually subjected to biasness due to the class structures of the accused. He emphasized that since judiciary itself has acknowledged its errors in such cases, one must abolish death penalty in all cases as it is gross violation of human rights. Mr. Surendranath also raised questions over the efficiency of police forces in carrying out interrogation process. He pointed out that our forces are not well equipped and sensitized which has resulted in cases of extreme torture and custodial killings which must be rectified. Anup stressed on the fact that repressive laws can never be a medium for deterrence and hence country should move towards reformative laws.

Rough Transcript:

Pranjal: Hello and welcome to Newsclick. India's law commission has recently released a report recommending that the country should move towards abolishing death penalty. To discuss the issue, we have with us Anup Surendranath who teaches constitutional law at National Law University in Delhi and he is also the Director, Centre on the Death Penalty. Hello Anup. The law commission has recommended that the death penalty should eventually be abolished but not in the cases of terror and it has said it should be done in order to safeguard the national security. So what do you think this issue of terror has left out specifically in way this law commission is heading towards?

Anup: I think the law commission is quite clear that there must be abolition of death penalty in all cases and I think they are very clear about that. But the exception to terrorism is suggested as a first step. They are saying in the first step, we must abolish death penalty except terror and it is surprising that the law commission finds favour fot this kind of terror exceptionalism because for the large part of the document, the law commission did a wonderful job of documenting why the death penalty be legitimized in constitution in India. But I think you rightly said the reasoning why we find this terror exceptionalism is quite weak and they have said that law makers, there is a lot of disagreement amongst law makers on this and it concerns the issues of national security, that the law makers disagree on the basis of national security and therefore, they are suggesting only as a first step that we abolish it all except terror but they are very clear that in principle, it must be abolished for. But unfortunately, I think even this first step the suggestion that the first step and then and some point later in time we will abolish it for terrorism is rather disappointing because if you look at 1967 report, it has taken almost 50 years for the law commission to consider it's position again and basically I think what has ended up happening is that now you entrenched it for terrorism even more. Yes, I think in principle it might say that, but politically, I think this report is going to be used to keep the death penalty for terrorism for much longer but the reasoning is quite weak. They don't really provide the reason as to why this must be the first step and not anything else or why the disagreement amongst the law makers is not relevant for other offenses but is relevant for this category of offenses.

Pranjal: There is a specific term which we use 'repressive laws'. They usually use it for a society where there is a mechanical solidarity which exists. The society which is old in nature and is bounded by customs as far as we are moving towards a modernized society, do you think repressive law is still a medium for deterrence? Does it help? Does it act as a deterrence for the people in the cases?

Anup: We interviewed all over India death row prisoners over 2 years and whatever views I have are based on what I have seen and heard from prisoners themselves and their families and their lawyers and very often I think we don't think of the so many of India's death row prisoners who are not the Yakub Memons or the the Kasabs or the Afzal Gurus. Yes, certainly those cases have their own significance and even debating death penalty in those cases is extremely important but what happens we rarely debate the much larger category of death row prisoners who are not in the national media attention. Nobody is discussing their cases and it is in those cases, that you really, if you want to really understand how the death penalty works in this country and the sort of atrocious manner in which prosecutions are conducted and convictions are gotten and that's where the real dangerous truth lies and I think after speaking to so many death row prisoners across the country, I think there is such a great logical fallacy in this deterrence argument when even amongst people who have committed these crimes and it's not like these are people sitting there and calculating at the moment of committing the offense, oh! Am I going to get caught? Am I going to get the death penalty? These are people who don't even know the offenses they are about to commit has the death penalty or doesn't have the death penalty. They are not calculating the risks and chances they will get caught, prosecuted or whatever and these are extremely poor people and with very little access to legal recourse and I think we need to worry about those things and the deterrence – questions can never really be answered and I don't think it can really be answered one way or the other and I think there are very very serious systemic issues that need to be looked into.

Pranjal: Anup you have raised a very important point of process of sentencing. Can you throw some light on that. During your research, did you find any specific thing which was not favourable in case of... like you also have also raised a point of class structure of these people. So is there any stark difference between the two cases?

Anup: There is a lot of discussion on this rarest of the rare and there is a lot of writing on how Supreme Court itself has not applied it consistently, the Supereme court itself has recognized it has got it wrong in some cases. Now, if you think that is bad, you really have to see how that standard is applied in the trial courts, in the district courts. You can not believe what they do with the standard. There is a complete break down of what rarest of the rare means or what it's constitutional requirements are as recognized in Bachan Singh. If you look at how trial courts conduct sentencing, it is really shameful. There is no really substantial sentencing hearing. Even the defense lawyers do not know what to argue in a sentencing hearing. Even the judges and prosecutors treat sentencing phase as some sort of formality. It's not done this distinction between your guilt and the punishment you must get for that is completely missing in that criminal justice system. It is as though you are the moment you are convicted for the crime, nobody is interested in a very serious, robust, sentencing practice. As so many other jurisdictions, any sensible and humane criminal justice system must pay attention to sentencing. Fortunately, we do not do that and unfortunately we do not do that for the harshest punishment in our system. So there is hardly any sentencing worth it's name. There is no rigor, there is no application of mind when it comes to sentencing. It is all only about how horrific is the crime.

Pranjal: Anup, the law commission report also says that the rarest of the rare case can not sustain. So what is the significance of this term called rarest of the rare case and what is the significance of the law commission saying that it can not sustain.

Anup: So while upholding the constitutionality of the death penalty in India, Supreme Court has said that it is applicable in the rarest of the rare case. Now, what is this meaning of rarest of rare case? Everybody seems to have this very commonsensical understanding that it is really kept for the most heinous crime. It is not that. It is said that in most rarest of rare instances should the death penalty be given and there are many criteria that are laid out in the judgment and it is not just the crime but also look at the circumstances of the criminal whether the criminal is capable of being reformed, can the state prove that this person is incapable of being reformed. Is any other option unquestionably foreclosed. But you will see a complete absence of consideration of these factors like reaffirmation, any other option unquestionably foreclosed, from the jurisprudence of the courts and that is why you see so much inconsistency in the application of the rarest of the rare. That is why it is a constitutionally inviable standard. It is inviable because it is not... see it is what is happening is not that I as a judge sort of justifiably impose it in one case and somebody else might have said no death penalty in this case. It is not a difference of opinion that's happening. Everybody thinks to think that that's the problem, that's somehow inherent in the adjudicatory process. In one case might think one punishment is required and somebody else might think that somebody else … difference of opinion but that's not happening with rarest of rare case. With the rarest of rare stand such is there is complete error in it's application, there is complete misunderstanding of what the standard itself requires. It is incapable of any further clarity. This kind of error is a very natural outcome of the way you have framed that standard. That error is going to keep happening. That is why the law commission felt and looking at it is quite evident from the case law and the court itself has recognized it's error in some cases.”Error” and I am again saying error not difference of opinion. You are getting in wrong in one case is bad enough for a legal system when it concerns the death penalty and very often when you discuss death penalty people say, oh! You are not executing so many people. You have executed four people in fifteen years. But we very often forget that the problem with the death penalty is not just the fact of hanging. It is experience of living on death row and that we very often forget.

Pranjal: If you keep aside this entire point of death penalty itself not only we have been missing on jail reforms, also we have been missing on police reforms and the entire process of restitutive laws. How to reform people. So the recent law commission report has also pointed out that country is in need of major political reforms and witness protections. Do you think that it is a positive move towards it?

Anup: Yes, I think again on the debate on the death penalty you will see that very little of the discussion happens how do you prosecute in this country. How do you get convictions in this country. We have an extremely unscientific police force. It's not a modern police force. We have not invested sufficiently in our police force. They do not have modern scientific methods of investigation of forensic sciences or whatever. So in that sense the only evidence the way they can get is by torturing people and world over it has been recognized that evidence collected on the basis of torture is extremely unreliable. People admit to things they have not done just to not be tortured. That is why we have very violent and corrupt police force and I don't blame this on individual policemen or police officers. They are functioning in a system where the system is sending the message to them. In that context, it is very important that we look at the quality of the evidence and this quality of the convictions and you can't be relying on such a criminal justice system to get convictions and death penalty cases. You know the kind of custodial torture that happens and how they sign statements and how recovery happens on the basis of those statements gotten out through tortures.

Pranjal: There have been various media coverages on it news on it that most of the people in this country who are in this country in prison belong to minority, are Dalits or Adivasis. What do you think that are the legal system in India biased towards a specific community and the second part of it will be the recent comments made by various judges in the country. People quoting from Manusmruti and Gita. Do you think the country moving positively as far as the judicial system is concerned.

Anup: I don't think any one of us would be in a position to know and I hope that the judges at the level at which they operate are sufficiently trained to keep these things out of the court room while they are deciding these cases. One sincerely hopes and the entirely edifice of our constitutional democracy are based on the fact that these things are not brought into the court room. Whether it happens like that or it does not happen like that, I have no way to say. But certainly what we can observe is who are getting trapped in the criminal justice system. If you look at the number of under trials in central India and the number of years that they kept in the prison as under-trials and the low rates of convictions, all that is very problematic information. Very problematic data that is coming through. When you ask me is there a discrimination in our legal system, my own position is there is no way for us to establish there is a direct discrimination. There is a no way for me to say that if a judge knows there is a Dalit before him or her that judge exercises a direct discrimination. But I think the way the legal system discriminates in it's structure be it how certain groups are able to interact with the police, how they are able to interact or not interact with the police or with the prosecution, or with lawyers or with various aspects of the legal system. Can they bring expert evidence? What kind of expert evidence can they bring? All those are very serious structural disadvantages that certain communities and groups have and as a result of that structural disadvantages, I think that is how they get ensnared in this sort of cobweb of our criminal justice system and only certain groups tend to members largely. So I think that's how discrimination operates. I think it was rather a claim that we can't really back if it says it is direct discrimination. We need a lot more empirical work and evidence to make that claim but the structural discrimination argument I think can very strongly made and I think that is the worry.

Pranjal: Thanks for giving us your time and as the things proceed we will be coming back to you on such issues. Thank you for watching Newsclick.

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for Newsclick are typed from a recording of the program. Newsclick cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.