Intersecting Identities Have Significant Effects on Women’s Participation in Labour Force, Says Study

Image Courtesy: Reuters

The male-female gaps in labour force participation rates (LFPR) in India are strong and persistent, as female labour force participation (FLFP) continues to decline from its already low level, according to a working paper published by Initiative for What Works to Advance Women and Girls in the Economy (IWWAGE). According to the paper, titled ‘Intersecting Identities, Livelihoods and Affirmative Action: How Social Identity Affects Economic Opportunity for Women in India”, the decline is majorly seen among rural women, especially Adivasi women.

The paper said, “There are several explanations advanced for the low level as well as the decline. Part of the problem is the inability of the statistical system to correctly count women’s economic work. Women are involved in economic work in far greater numbers than labour force statistics can capture. Additionally, the registered decline has been in paid employment, and not in women’s reproductive labour.”

The paper has been authored by Ashwini Deshpande, Professor of Economics at Ashoka University, and is an output of the research vertical of the Initiative for IWWAGE, an initiative of Leveraging Evidence for Access and Development (LEAD) at Krea University. IWWAGE aims to build on existing research and generate new evidence to inform and facilitate the agenda of women’s economic empowerment.

The other important dimension characterising gender gaps in the labour market relates to wage gaps and employer discrimination. Over the decade which saw a fall in women’s labour force participation rate, women’s educational attainment increased sharply, the paper pointed out. It said, “Thus, in 2010, if women were ‘paid like men’, the average wages of women would be higher than those of men. The fact that men earn higher wages/salaries after accounting for wage-earning characteristics reveals substantial wage discrimination.”

It added, “The intersection between gender and social identities such as caste and tribe indicate that Dalit women, disadvantaged on account of caste, poverty, and patriarchy, are the worst-off in terms of material indicators, as well as on autonomy and mobility indicators.”

According to the author, gender gaps in self-employment are even larger than those in wage employment. Policies such as the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) designed to encourage self-employment have had several other positive impacts, such as an increase in empowerment and autonomy, but their record in terms of enhancing livelihoods is mixed at best

LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION AND UNEMPLOYMENT RATES

India has among the lowest LFPRs in the world, well below the global average of 50%, and the East Asian average of 63%. As per the National Sample Survey (NSS), the estimate of the labour force in the usual status includes (a) the persons who either worked or were available for work for a relatively larger part of the 365 days preceding the date of the survey and (b) those persons from among the remaining population who had worked for at least 30 days during the reference period of 365 days preceding the date of the survey.

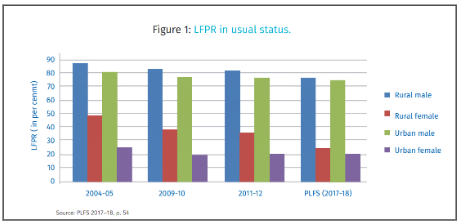

The above graph reveals that first, male LFPRs for all the years are significantly higher than females, and the gap between the two has been increasing over the years. Second, there is no significant difference between rural and urban LFPRs for men; however, for women, rural LFPRs have been higher than urban for all years. Third, while male LFPRs have also declined slightly over the period by nearly 10 percentage points for rural men (from nearly 87% to 76.4%) and urban men (80% to 74.5%), female LFPRs have registered a sharp decline, especially in rural areas. Rural female LFPRs declined by 25 percentage points (from roughly 50% to 25%), whereas urban female LFPRs continued their historically low levels, and declined slightly (from roughly 22% to 20%).

WAGE GAPS

The paper said, “In contrast to Western developed economies, gender wage gaps in India (similar to China and several other countries) exhibit a sticky floor, and not a glass ceiling, i.e. these are higher at the bottom of the wage distribution than at the top.”

It explained the one reason behind the sticky floor might be the statistical discrimination by employers. It said, “In India, social norms place the burden of household responsibilities disproportionately on women. Because of this, men are perceived to be more stable in jobs vis-à-vis women. Given the higher probability of dropping out of the labour market, employers discriminate against women when they enter the labour market because they expect future career interruptions.”

It added that as women move up the occupation structure and gain job experience, employers become aware of their reliability and therefore discriminate less. Men usually have more work experience or tenure than women on average. The paper said, “ Women who have high levels of education and are at the top end of the distribution might be perceived to have high levels of commitment, and due to their past investments in education are thought to be stable employees.”

At the higher end of the wage distribution, the nature of jobs is very different from those at the bottom. The women working in these jobs are more likely to be the urban educated elite working in managerial or other professional positions. These high-wage-earning women are more likely to be aware of their rights and might be in a better position to take action against perceived discrimination, according to the paper.

The author presented this in contrast with a situation where an employer is paying a regular wage to a woman with no education working in an elementary occupation, which is a typical example of a worker at the bottom of the wage distribution in the Indian context. The paper said, “It is easier for the employer to discriminate in this case, as these jobs are in the informal sector and outside the jurisdiction of labour laws. Women at the bottom have less bargaining power compared to men due to family commitments or social custom and are more likely to be subject to the firms’ market power. Thus, a sticky floor could arise because anti-discriminatory policies are more effective at the top of the distribution.”

It pointed out that job segregation is also a known contributor to wider gaps at the bottom as men and women-only enter into exclusively ‘male’ and ‘female’ jobs. Low-skilled jobs for women may pay less than other jobs that require intense physical labour, which men typically do.

EFFECTS OF CASTE HIERARCHY

The effects of caste hierarchy are reflected in the differential LFPRs of women, the paper said, such that upper caste women have historically had lower labour force participation compared to Dalit and Adivasi women because working for wages has been seen as a marker of low status. “This is compounded by the fact that the taboos on public visibility are greater for upper caste women compared to lower caste women,” it said.

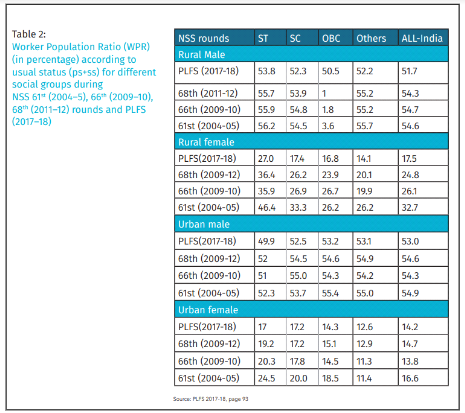

Caption - PLFS: Periodic Labour Force Survey

The above table shows that the caste gaps in WPRs for men are minuscule. Gaps in social groups in LFPRs are mainly due to the gaps in female LFPRs. Examining the decline in terms of the gender-social group overlap, the researchers found that both in rural and urban areas, LFPRs of ST or Adivasi women have declined the most, followed by rural Dalit women. Between 2004-05 and 2017-18, the decline in ST female LFPRs has been 19.4 percentage points in rural areas and 7.5 percentage points in urban areas. The corresponding decline for SC women has been 16 and 3, for OBC women 16 and 4, and upper caste women 12 and 1 percentage points, for rural and urban areas, respectively.

The paper said, “The landscape of male–female disparities as well as intersectionality between gender and social identity reveals that with the exception of school education, the gaps between men and women, as well as within the different social groups within women, are either static or increasing.”

It concluded by saying that gender equality in various economic dimensions and women’s economic empowerment remains a significant challenge in India. “It is clear that economic growth, whether high or low, is not the main factor in shifting the needle on gender equality. Evidence for India shows that a variety of policies impact gender equality; therefore, gender needs to be mainstreamed into the entire policymaking apparatus, and not be compartmentalised into a secondary priority,” the paper said.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.