How to Really Compensate for Injustice Committed

Someone must have been telling lies about Joseph K, he knew he had done nothing wrong but one morning, he was arrested.

These opening lines of Franz Kafka’s classic novel, The Trial, published just over a century ago, in 1925, still ring true.

Joseph K, the novel’s protagonist, is cashier at a bank. On his 30th birthday, two unidentified agents arrest him for an unspecified crime. The plot of the novel revolves around his efforts to deduce what the charges against him are, and which never become explicit. Joseph K’s feverish hopes to redeem himself of these unknown charges fail and he is executed at a small quarry outside the city—“like a dog”—two days before his 31st birthday.

Kafka, a major figure of 20th century-literature died of tuberculosis in 1924, when he was barely 40 years old. He had wanted all his manuscripts, including of the unfinished The Trial, destroyed after his death, but close friend and executor of his will, Max Brod, ignored the instruction and the world gained a strong literary indictment of an apathetic and inhuman bureaucracy and how completely it can lack respect for civil rights.

Kafka’s novel resonates with us today for it is not difficult to spot people who have been wronged by our system. Their endless wait for justice, especially those charged with petty crimes, or those who spend the prime of their lives behind bars on concocted charges, is on open public display.

Who can forget young Aamir, who had to spend fourteen years imprisoned for—as the prosecution claimed—involvement in 18 bomb blasts that took place in and around Delhi. None of those charges could stand scrutiny before the courts and as they fell apart, one by one, he was finally acquitted in 2012. Their tortuous struggle for the release of their innocent son left Aamir’s father dead before the acquittal, while his mother was paralysed and lost her speech.

Aamir recorded his own trials and tribulations in Framed as a Terrorist, published in 2016, a book which would perhaps not have materialised had the rights activist and writer Nandita Haksar not taken interest in this case. Filled with poignant details of the institutional bias ingrained in India’s administrative system, the book explains exactly how the system works against people who belong to socially and culturally marginalised communities.

The recent acquittal of Dr Kafeel Khan—who used to work at the BRD Medical College in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, where scores of children had died two years ago due to a sudden halt in oxygen supplies—after spending more than seven months in jail brings home the point once again. Khan’s incarceration has been termed “illegal” by the Allahabad High Court, but the powers-that-be were still able to wreak havoc in the life of an ordinary law-abiding citizen. When the system becomes immune to the sufferings of people or intoxicated with its own agenda, then there is little that can help citizens.

Remember, the Uttar Pradesh government most recent accusation against Dr Khan was that he had broken “peace and tranquillity”. It is a charge that had led to the imposition of the stringent National Security Act, whose provisions also seek to penalise terrorist activities. Yet Khan’s only “crime” was that he had delivered a speech at the Aligarh Muslim University campus while the nationwide anti-CAA and anti-NRC protests were taking place. He was arrested more than two months after the speech. Anyone who hears it would have no doubts that the state police had resorted to extreme measures in response to an otherwise innocent speech. Somehow, the authorities twisted a speech that focussed on unity and integrity of the nation into a seditious speech. This is what the High Court’s order securing his acquittal confirms.

As for the charges lodged against him under the National Security Act, the court declared that a complete reading of his speech does not disclose any effort to promote hatred. It notes, “It appears that the District Magistrate had selective reading and selective mention for few phrases from the speech ignoring its true intent.”

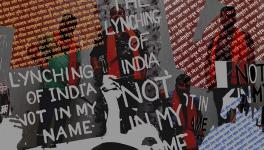

The question arises, how can it be ensured that there are no more Kafeel Khans or Aamirs in India’s future. There is also the question of how the innocent who are put through such trials be compensated for their suffering?

The easiest option before the state is to provide some monetary compensation to people who have been patently wronged by the system. For instance, the National Human Rights Commission recently asked Chhattisgarh government to compensate activists and scholars who had visited the state to enquire into the human rights situation there, but whom the previous government had filed concocted FIRs against. The NHRC has observed, “...these persons would have certainly suffered a great mental pain and agony as a result of registration of false FIRs against them by the police, which is a violation of their human rights and for this the state government should compensate them.”

All this is fine, but can financial compensation make up for the years lost of all the people who have been wrongly accused and tried? The mental trauma such victims go through, the loss of their near and dear ones that inevitably follow many such instances, their loss of livelihood, education, reputation, and their being condemned to loneliness behind iron bars—can money be a recompense for all of these?

One is reminded of a photograph which went viral recently. In it depicted a Black man, acquitted of the charges against him after he had already spent many years imprisoned. An official appears to be consoling him in the picture, and is shown to be offering him a blank cheque. The man is purportedly free to write up any amount he wishes as compensation for his suffering and the lost year. The response of the man as depicted in the picture is stunning: “Sir, can that amount bring back my wife, my children who died in utter poverty when I was rotting in jail for no crime of mine?”

It is of course also a fact the idea of compensation to wrongly-accused persons has not yet reached the statue books. There was an instance in (united) Andhra Pradesh where the government had announced compensation to be awarded to 16 people who had been tried and later acquitted in the 2007 Mecca masjid blast case. This was after persistent pressure from human rights groups. The compensation was an indirect admission that these people had been wrongly implicated in the case. But within a year and a half, the High Court intervened in the matter, cancelled this compensation, and sought its recovery from those who had already got it. The court ruled that “mere acquittal or discharge from a criminal case cannot be basis for payment of compensation”. Another judgement by the Supreme Court in 2014 firmly rejects such compensation, because it felt it would establish an unwelcome precedent.

In any case, the best antidote to illegal arrests, incarceration and torture is to ensure that the guardrails of democracy, the institutional mechanisms of the Constitution and its checks and balances function as they were meant to. If the executive appears to be transgressing the rights of individuals or groups, the judiciary should step in, even suo motu, or the legislature must influence the system to foster respect for human rights.

Seventy-year-old Bhatki Begum, from Tragpora, Rafiabad, in Baramulla district of Jammu and Kashmir, whose 28-year-old son Manzoor Ahmad Wani had disappeared while in the Army’s custody in 2001, should have been able to approach the authorities without fear and not have to wait for 19 years for justice. It is only recently that an Ikhwani (government gunman) involved in the abduction of Manzoor Wani, was convicted.

The legislature will, some day, have to take a call on officials who violate human rights and discipline them so that such incidents do not recur. Normally, this task is brushed aside with the false logic that punishing the guilty will “demoralise” the police force or the bureaucracy. Perhaps there is need to reiterate our commitment to Article 21 of the Constitution, which specifically says that “no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.” What is really demoralising, for all of us, is when the Constitution is not followed in both letter and spirit.

The author is an independent journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.