How Racism Caused the Shutdown

This isn’t an article about how Republicans shut down the government because they hate that the President is black. This is an article about how racism caused the government to shut down and the U.S. to teeter on the brink of an unprecedented and catastrophic default.

I understand if you’re confused. A lot of people think the only way that racism “causes” anything is when one person intentionally discriminates against another because of their color of their skin. But that’s wrong. And understanding the history of the forces that produced the current crisis will lay plain the more subtle, but fundamental, ways in which race and racism formed the scaffolding that structures American politics — even as explicit battles over race receded from our daily politics.

The roots of the current crisis began with the New Deal — but not in the way you might think. They grew gradually, with two big bursts in the 1960s and the 1980s reflecting decades of more graduated change. And the tree that grew out of them, the Tea Party and a radically polarized Republican Party, bore the shutdown as its fruits.

How The New Deal Drove The Racists Out

In 1938, Sen. Josiah W. Bailey (D-NC) filibustered his own party’s bill. Well, part of his party — Northern Democrats, together with Northern Republicans, were pushing an federal anti-lynching bill. Bailey promised that Southern Democrats would teach “a lesson which no political party will ever again forget” to their Northern co-partisans if they “come down to North Carolina and try to impose your will upon us about the Negro:”

Just as when the Republicans in the [1860s] undertook to impose the national will upon us with respect to the Negro, we resented it and hated that party with a hatred that has outlasted generations; we hated it beyond measure; we hated it more than was right for us and more than was just; we hated it because of what it had done to us, because of the wrong it undertook to put upon us; and just as that same policy destroyed the hope of the Republican party in the South, that same policy adopted by the Democratic party will destroy the Democratic party in the South.

Bailey’s rage at the affront to white supremacy was born of surprise. Until 1932, the South had dominated the Democratic Party, which had consistently stood for the South’s key regional regional interest — keeping blacks in literal or figurative fetters — since before the Civil War.

But the Depression-caused backlash against Republican incumbents that swept New Yorker Franklin Roosevelt into the White House and a vast Democratic majority into Congress also made Southerners a minority in the party for the first time in its history. The South still controlled the most influential committee leadership votes in Congress, exercising a “Southern Veto” on race policy. The veto forced FDR to stay out of the anti-lynching fight (“If I come out for the anti-lynching bill, [the southerners] will block every bill I ask Congress to pass to keep America from collapsing,” he lamented).

The veto also injected racism into the New Deal. Social Security was “established on a racially invidious, albeit officially race-neutral, basis by excluding from coverage agricultural and domestic workers, the categories that included nearly 90 percent of black workers at the time,” University of Pennsylvania political scientist Adolph Reed Jr. wrote in The Nation. “Others, like the [Civilian Conservation Corps], operated on Jim Crow principles. Roosevelt’s housing policy put the weight of federal support behind creating and reproducing an overtly racially exclusive residential housing industry.”

Yet, Reed notes, the New Deal not only benefited blacks, but brought them to a position of power in the Democratic Party. “The Social Security exclusions were overturned, and black people did participate in the WPA, Federal Writers’ Project, CCC and other classic New Deal initiatives, as well as federal income relief,” he reminds us. “Black Americans’ emergence as a significant constituency in the Democratic electoral coalition helped to alter the party’s center of gravity and was one of the factors–as was black presence in the union movement–contributing to the success of the postwar civil rights insurgency.”

Hard evidence of the Northern Democrats’ radicalization on civil rights, outflanking the GOP, can be found by the early 1940s. UC-Berkeley’s Eric Schickler and coauthor Brian Feinstein built a database of state party platforms from 1920-1968 and examined their positions on African-American rights. They found that “the vast majority of nonsouthern state Democratic parties were clearly to the left of their GOP counterparts on civil rights policy by the mid-1940s to early 1950s.” African-Americans and other sympathetic New Deal Coalition constituencies, like Jews and union leaders, deserve the bulk of the credit — these new Northern Democrats made supporting civil rights a litmus test for elected Democratic officials. That explains why, from the Early New Deal forward, congressional Northern Democrats voted more like Northern Republicans than their Southern brethren on civil rights.

Schickler and Feinstein pair the shift on civil rights to the parties’ broader post-New Deal ideological shifts. New Deal liberalism’s vehement support for government intervention in the economy made Democrats more open to the sorts of intrusive economic regulations, like desegregating private businesses, that civil rights campaigners demanded. Meanwhile, “the GOP’s ties with chambers of commerce, manufacturers’ associations, real estate groups, farm lobbies, and other organizations opposed to the increased government oversight of private enterprise that would come with fair employment and other civil rights legislation encouraged the GOP’s drift toward racial conservatism.” As Speaker of the House Joe Martin (R-MA) told an assembly of black Republicans in 1947:

I’ll be frank with you: we are not going to pass a [non-discrimination in private business bill], but it has nothing to do with the Negro vote. We are supported by New England and Middle Western industrialists who would stop their contributions if we passed a law that would compel them to stop religious as well as racial discrimination in employment.

Republican economic libertarianism, together with its gradual embrace of traditionally Southern “states rights” arguments to as weapons in the war on the New Deal, set the stage for the eventual white flight from the Democratic Party.

And Southern Democrats, without whose votes the New Deal never could have happened, were willing to sacrifice their commitment to economic liberalism on the altar of white supremacy. Historian Ira Katznelson, whose 2013 work Fear Itself focuses on the role of Southern Democrats in the New Deal, analyzed Congressional votes from 1933 to 1950 to better understand the political alliances of the time. Katznelson and his coauthors focus on the votes of Southern Democrats on six issues: “planning, regulation, expansive fiscal policies, welfare state programs, a national labor market and union prerogatives, and civil rights.”

The Southerners, as Democrats, strongly supported the first four, but bucked the Northern wing of the party on the last two. But why labor in addition to civil rights? Katznelson et al. find a precipitous dropoff in Southern support for pro-labor laws during World War II, one of the two key reasons being that “wartime labor shortages and military conscription facilitated labor organizing and civil rights activism.” “Labor market and race relations rends and issues,” they found, had become “conjoined.” For Southern Democrats, racism trumped liberalism.

Hence the famous Dixiecrat revolt of 1948, when Strom Thurmond and likeminded Southerners temporarily seceded from the Democratic Party over Harry Truman and the Democratic platform’s support for civil rights. The tacit bargain that Katznelson documents during the Roosevelt Administration, in which the Northern Democrats would get their New Deal if the Southern Democrats got their white supremacy, became untenable.

But the Dixiecrats weren’t ready to migrate en masse to Party of Lincoln just yet. Something needed to happen to make the Republican Party shed its commitment to leading on civil rights wholesale. That “something” was the rise of the modern conservative movement.

‘The Great White Switch’

Earl Black and Merle Black are twin brothers. Both are political scientists at (respectively) Rice and Emory University. The twins, frequent coauthors, are widely considered to be the deans of the study of Southern politics.

In their book The Rise of the Southern Republicans, the Blacks pinpoint two key transition points for Southern whites when the trends we’ve already seen produced truly marked change. By the 1950s, the splits between Northern and Southern Democrats in Congress had become irreconcilable. The party’s leadership was “refusing to call party meetings” for fear of catastrophe.

The Southern Democrats had to form alliances with the more conservative wing of the Republican Party. In a reverse replay of the South’s deal with Roosevelt and Northern Democrats, the Blacks found, Southern Democrats helped Republicans fight Truman’s economic policy while Republicans protected the Southern right to filibuster, allowing them to retard progress on civil rights without alienating black voters by voting against any particular piece of civil rights legislation. This “Inner Club” of Southern Democrats and conservative Republicans “informally set the limits on passable legislation.”

But it wasn’t until Barry Goldwater and the rise of the modern conservative movement that this marriage was formally consummated. Goldwater lost all but six states — Arizona, his home, and five Deep South states. It was the first time the GOP had prevailed at the presidential level in the South in the party’s history. Republicans have held the South since.

Goldwater, a Sun Belt Senator who believed in integration, seemed like an odd choice to inspire Southerners to leave LBJ, a Texan with a storied racist past. But that surface level-analysis entirely misses the role of the Goldwater-led conservative movement in the Southern imagination.

By the Johnson-Goldwater election, it had become clear that overt racism and segregationism was politically doomed. Brown v. Board of Education and LBJ’s support for the 1964 Civil Rights Act saw to that. As this scary recognition dawned on Southern whites, they began searching for a new vehicle through which to shield themselves and their communities from the consequences of integration. The young conservative movement’s ringing endorsement of a minimalist federal government did the trick — it provided an on-face racially neutral language by which Southerners could argue against federal action aimed at integrating lily-white schools and neighborhoods.

Kevin Kruse, a Princeton historian whose work focuses on the South and the conservative movement, finds deep roots in segregationist thought for this turn. “In their own minds, segregationists were instead fighting for rights of their own,” Kruse suggests. These “rights” included “the ‘right’ to select their neighbors, their employees, and their children’s classmates, the ‘right’ to do as they pleased with their private property and personal businesses, and, perhaps, most important, the ‘right’ to remain free from what they saw as dangerous encroachments by the federal government.”

Kruse traces this language through white resistance to desegregation from the 40s through the 60s, using a detailed examination of “white flight” in Atlanta as a synecdoche. In the end, he finds, “the struggle over segregation thoroughly reshaped southern conservatism…segregationist resistance inspired the creation of new conservative causes, such as tuition vouchers, the tax revolt, and the privatization of public services.” The concomitant rise of the modern conservative movement and the civil rights movements’ victories conspired to make Southern whites into economic, and not just racial, conservatives.

Kruse’s theory isn’t based on mere anecdote. M. V. Hood, III, Quentin Kidd, and Irwin L. Morris’ book The Rational Southerner arrays a battery of statistical evidence correlating Southern whites’ Republican turn with black voter mobilization. The more politically active blacks became, their data suggest, the more whites flocked to conservative Republicans as a counter.

So from 1964 on, conservative white Southerners voted against Democrats at the presidential level. But the en masse formal switch in party identification until Reagan. “Reagan’s presidency,” Merle and Earl Black write, “was the turning point in the evolution of a competitive, two-party electorate in the South. The Reagan realignment of the 1980s dramatically expanded the number of Republicans and conservative independents in the region’s electorate.” The Blacks attribute this to a combination of Reagan’s winning political personality and (more persuasively) the relative prosperity of the 1980s. Not only were white conservatives ideologically inclined to support Reagan’s Republican Party, but they became wealthier on his watch.

Reagan-era conservatism also left behind the naked racism that had driven Southern Democrats out of the party, which the civil rights movement had rendered unacceptable. By 1983, even Strom Thurmond, the former Dixiecrat candidate for President, voted to make Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday a national holiday. Reagan-era conservatism, while hardly above race-baiting, became far more about foreign policy hawkishness, Christian-right style social conservatism, and — most importantly for present purposes — free market economics.

The South’s conversion to movement conservatism led to local and Congressional Republican victories throughout Dixie. These culminated in the Gingrich Revolution in 1994, when hard-line Southern conservatives took charge of the Republican Congressional delegation, seemingly for good.

Sen. Bailey’s prediction had finally come true. The Democrats’ about-face on race cost them the South.

The Legacy Of The Democratic South’s Rebellion: The Tea Party

We all know what happens next. The Southern conservative takeover of the Republican Party pushes out moderates, cementing the party’s conservative spiral. This trend produces the Tea Party, whose leading contemporary avatar — Ted Cruz — engineers the 2013 shutdown and risk of catastrophic default.

So we can draw a tentatively straight line between the last 80 years of racial politics and this week’s political crisis. Aside from being an interesting point of history, what does that tell us?

First, that the shutdown crisis isn’t the product of passing Republican insanity or, as President Obama put it, a “fever” that needs to be broken. Rather, the sharp conservative turn of the Republican Party is the product of deep, long-running structural forces in American history. The Republican Party is the way that it is because of the base that it has evolved, and it would take a tectonic political shift — on the level of the Democrats becoming the party of civil rights — to change the party’s internal coalition. Radicalized conservatism will outlive the shutdown/debt ceiling fight.

Second, and more importantly, the battle over civil rights produced a rigidly homogenous and disproportionately Southern Republican party, fertile grounds for the sort of purity contest you see consuming the South today. There’s no zealot like a new convert, the saying goes, and the South’s new faith in across-the-board conservatism — kicked off by the alignment of economic libertarianism with segregationism — is one of the most significant causes of the ideological inflexibility that’s caused the shutdown.

That’s not to dismiss the continued relevance of race in the Southern psyche. There’s no chance that, when 52 percent of voting Americans are over 45, the country has just gotten over its deep racial hang-ups. Read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ masterful “Fear of a Black President” if you don’t believe me.

Naturally, the South remains Ground Zero. One 2005 study that measured racial animus found that Southern whites were “more racially conservative than whites elsewhere on every measure of racial attitudes ordinarily used in national surveys.” And Obamacare is a racially polarized issue. Brown University’s Michael Tesler found, in 2010, that there was an astonishing 20 point higher racial gap on health policy in 2009 than there was in the early 90s. In Tesler’s experiments, subjects’ responses to statements about health policy were “significantly more racialized” when the statement was attributed to President Obama than President Clinton.

So it’d be implausible, to put it mildly, to say that modern racism has nothing to do with the shutdown fight. That being said, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly what its role is, and it’d be overly simplistic to reduce the whole shebang to racial animus. One of historical racism’s many political children — our right-polarized South — has to play an important role, one that’s independent of ongoing racial prejudice.

The basic idea goes something like this. Southern white flight from the Democratic Party, motivated as it was by the compatibility of purist economic libertarianism with de facto segregation, produced especially conservative Republicans. This hardline opposition to intervention in the marketplace survived the death of open segregationism, and as Southerners became more and more critical to the Party’s national fortunes, their brand of libertarianism gradually began to dictate the party’s ideological agenda. Primaries enforced the party line nationally, driving out moderate non-Southern Republicans and making the party’s representatives nationally fit the Southern-cast mold.

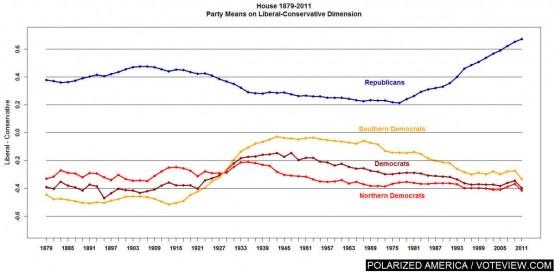

There’s certainly suggestive evidence to this point. Take a look at this chart of trends in House DW-NOMINATE scores — a measure of a legislator’s distance from the ideological mean of the time:

Notice how that sharp tick toward conservatism among Republicans starts around 1976, just when Southern whites were abandoning the Democratic Party in droves. At the same time, Southern Democrats start looking more and more like Northern Democrats (the story is basically the same in the Senate). It seems like Republicans became more conservative just as they were starting to become more Southern.

There’s more. “After the 1994 elections, white Southern Republicans accounted for sixty-two members of the 230-member House GOP majority,” Ari Berman writes in the most recent edition of The Nation. “Today, white Southern Republicans account for ninety-seven members out of the 233-member House GOP majority.” The percentage of Southerners in the GOP House caucus, Berman reports, has gone up in every election but one since 1976.

These Southerners also make up large percentages of the House’s most conservative blocs. Though Southerners make up a little over 30 percent of the U.S. population and 42 percent of House Republicans, a full 60 percent of the House Tea Party Caucus is Southern. Southerners comprise 50 percent of the Republican Study Committee, the House “cabal” so powerful in the past three years that, according to National Journal, ” the RSC’s embrace or rejection of any legislative effort has become the surest indicator of whether it will pass the chamber.” 19 of the 32 House Republicans the Atlantic deemed “most responsible” for the shutdown hail from the South.

Southern Congresspeople voted consistently more conservatively than their northern colleagues on the “fiscal cliff” deal that resolved the last debt ceiling standoff. Southern Republicans in more competitive districts, according to The New Republic’s Nate Cohn, voted more ideologically than Northern Republicans in safe GOP districts.

This shouldn’t surprise anyone: the South has been setting the Republican agenda since the 1994 Gingrich Revolution, both at the Congressional and the base level. Political scientist Niccol Rae conducted a series of interviews with House members in power from 1994-1998, finding that the “southern members of the Republican class of 1994 have acted as the ‘conscience’ or ‘keepers of the flame’ of this Republican revolution.” The enduring consequence, according to Rae, was finalizing the long-term demographic trends that were making the Southern bloc into “the dominant element, regionally, ideologically, and culturally in the congressional GOP.”

As the Southern faction became the face of the GOP in the mid-90s, the GOP’s electorate became a lot more conservative nationally. Panel data reviewed by Alan Abramowitz and Kyle Saunders found that, from 1992-1996, ideological conservatives joined the Republican Party in droves. That’s because Southern elites played a key “signalling” role; their prominent national conservatism signaled to conservatives around the country that the Republican Party was theirs.

Penn’s Matthew Levendusky, who literally wrote the book on conservatives “sorting” themselves into the Republican Party, says that “even when the data are consistent with a nationalization hypothesis, the South still played a crucial role in the sorting process because of the key role of Southern elites.” As conservative Southern elites took over the Republican Party, hyper-conservative Americans followed, becoming the GOP primary voters we know and love today.

So, to sum up: the South’s race-inspired conversion to radical conservatism made the GOP pure enough to threaten default over Obamacare in two distinct ways. First, Southern elected leaders are simply more conservative than other Republicans, and are making up a larger-and-larger percentage of total Republican seats in the House. Second, Southern elites send out signals that drive out moderate primary voters throughout the country, making even non-Southern Republicans more conservative.

In Dinotopia, a famous children’s book, the residents of a fictional dinosaur-human city use a water clock shaped like a helix. It’s a reflection of their novel concept of time. Instead of thinking of the passage of time as either linear or cyclical, they see it as a spiral: history forever repeats itself, but with new, unpredictable twists tossed in.

It’s a neat metaphor for the role of North-South conflict in the United States. The basic cleavage between North and South, began by slavery, has set the fault lines of American politics again and again. This time, the crisis isn’t as severe as the civil war, nor as divisive as the battle over civil rights. But make no mistake: today’s Republican radicalism, with all of its attendent terrifying brinksmanship, is the grandchild of the white South’s devastating defeats in the struggle over racial exclusion.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.