How to Overcome Poverty in India

Representational Image. Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Denizens of the neoliberal project are quite insistent that there has been a significant decline in poverty in the world, including India, in the neoliberal phase of the capitalist system. They tend to argue as follows: first, there has been an acceleration of the rate of growth of output; second, this higher rate of growth will increase the wage bill in real terms; third, this increase in the wage bill in real terms will reduce the share of population which is below the poverty line.

All three lines of argument are at best debatable in the context of the Indian economy since 1991. To begin with, most of the growth of the Indian economy since 1991 is arguably in the service sector where there are important conceptual issues regarding national income accounting especially regarding value added by public services.

Besides, it has also been argued that the estimates about the national income contribution of the medium, small and micro enterprises are failing to account for the impact of repeated adverse shocks (demonetisation, goods and service tax, policy response to Covid-19 etc.).

Further, an increase in the wage bill could involve a sufficiently large increase in wages and salaries or employment. Alternatively, the wage bill could rise if both the wage rate and employment increased.

But India, after 1991, has transitioned initially to jobless growth and later to job-loss growth. Moreover, the existence of a surplus labour (unemployment, underemployment and precarity) tends to reduce real wages. Inclusion of “salaries” of top management of the private organised sector in wages and salaries distorts the actual magnitude of the latter (and is better included as part of profits). In other words, there is little basis for arguing that the wage bill has increased substantially in India in real terms after 1991.

Lastly, there have been intense debates about the magnitude of the poverty line income in India. Poverty in India is inextricably tied to a calorie norm, namely 2,200 calories per person per day in urban India and 2,400 calories per person per day in rural India. Apart from food, the person who obtains the poverty line income is estimated to consume a certain bundle of non-food commodities, too. Now the practice of revising the prices of these commodities to periodically recalculate the revised poverty level of income misses out a key feature of neo-liberal India, namely, that some commodities available in the past in certain quantities are no longer available in the present in the same quantity in a given time period. Let’s see how.

Health, education etc., prior to 1991, were publicly provided in certain quantities virtually free of cost to the poor. While health, education etc. are counted as being publicly provided virtually free of cost even now, the actual magnitudes that are so provided have steeply declined due to decline in public expenditure since 1991. This has resulted in non-price rationing in the form of long queues or decline in quality or some combination of both. The resulting increase in out of pocket expenditure and its consequences are not captured in the official estimates of the poverty line income resulting in underestimation of the incidence of poverty in India.

Apart from these three processes, there also exists the phenomenon of historically unprecedented inequality in neoliberal India. As the World Inequality Report of 2024 starkly illustrates, the richest 1% of Indians now control over 40% of the nation’s wealth, while the bottom 50% are left with a mere 3%. This staggering concentration of wealth is a fundamental feature of the neoliberal model that has dominated India.

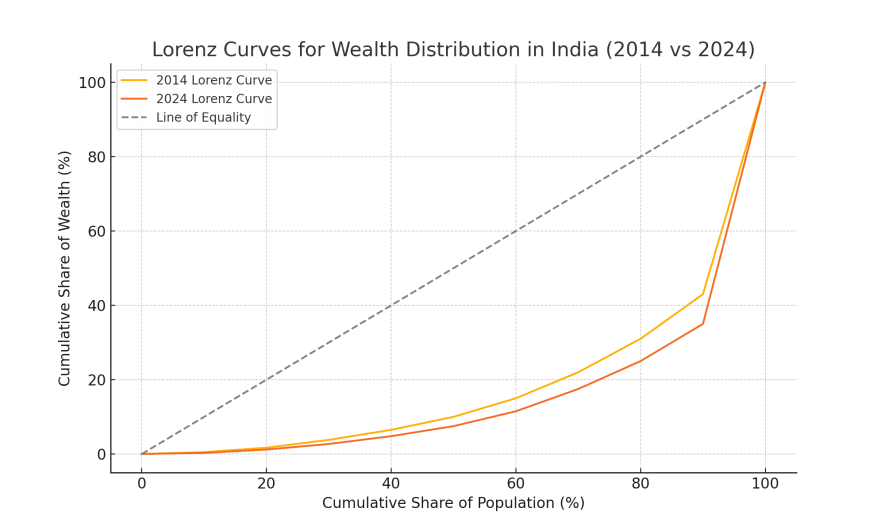

Consider the Lorenz curves in Figure 1, they indicate the cumulative share of wealth held by each decile of the population in India for the years 2014 and 2024.

Figure 1: Lorenz Curves for Wealth Distribution in India (2014 vs 2024).

Source: Author’s calculations based on: Oxfam Reports, World Bank Reports, World Inequality Database (WID)

The Lorenz curve for 2024 wealth distribution lies further away from the line of equality (45- degree dotted line in Figure 1) compared with 2014, indicating an increase in wealth inequality over this period. Moreover, the bottom deciles hold an even smaller share of wealth in 2024 resulting in the top deciles controlling a larger proportion compared with 2014. The Gini coefficients for wealth distribution (that may be computed from the data underlying the Lorenz curves for wealth inequality) in India have increased from 0.633 in 2014 to 0.689 in 2024.

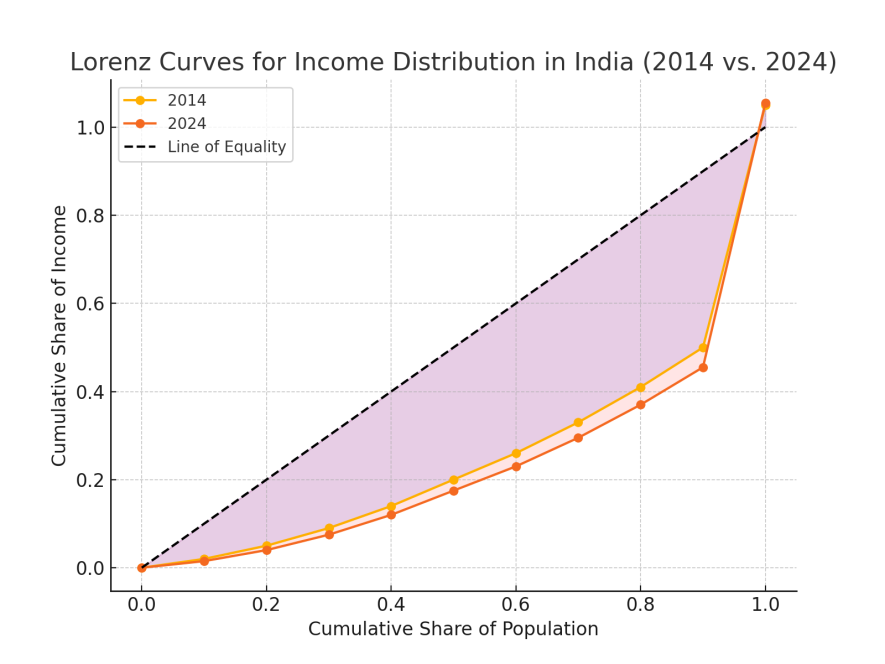

Similarly, the Lorenz curves for income distribution in India for 2014 and 2024 are illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2: Lorenz Curves for Income Distribution in India (2014 vs 2024).

Source: Author’s calculations based on: Oxfam Reports, World Bank Reports, World Inequality Database (WID)

In 2014, the bottom 50% of the population held about 15-20% of the total income, The top 10% captured approximately 55-60% of the total income. The middle 40% (5th to 9th deciles) accounted for around 25-30% of the total income. Now, in 2024, the share of the bottom 50% of the population has slightly decreased or remained stagnant, holding around 13-17% of the total income. The top 10% has seen an increase, now capturing about 60-65% of the total income. The middle 40% has faced a decline, holding about 20-25% of the total income.

The data shows that the share of income held by the top 10% has increased over the decade at the expense of everybody else, indicating growing income inequality. The bottom 50% and middle 40% have experienced a relative squeeze due to the proliferation of the neoliberal project that has involved both real wages not rising as fast as labour productivity (wage stagnation in fact) and the centralisation of capital that is facilitated by the government.

Analogous to the trend in wealth inequality, the Gini coefficient for income inequality too has increased from approximately 0.49 in 2014 to around 0.53 in 2024.

If income inequality rises sufficiently faster than growth, then this rise will exacerbate poverty. Further, the rise in wealth inequality is not only because of the rise in income inequality but also because of the persistent primitive accumulation of capital (involving the pauperisation of petty producers).

The persistence of poverty in India cannot be understood without confronting the deep-seated structural inequalities (that are linked to social oppression) that continue to plague the country. Caste discrimination, gender inequality, and regional disparities are not merely historical artefacts; they are living realities that shape the daily lives of hundreds of millions of Indians.

Therefore, the denizens of the neoliberal project fail to take into account that poverty in neoliberal India is dialectically determined by the interrelatedness of economic exploitation and social oppression. Dalits, Adivasis, minorities (especially Muslims) and other backward castes face systemic barriers that prevent them from equally participating in the economy either as business owners, landowners (including rich and middle peasants) and as relatively high wage workers.

Similarly, women in neoliberal India are disproportionately affected by poverty, a reality that is both a cause and a consequence of their lower (or lack of) asset ownership, attenuated levels of education, limited access to healthcare, and restricted employment opportunities. The latter is exemplified by the gender gap in paid labour force participation which remains one of the widest in the world, with women constituting only 20.3% of the paid workforce as of 2022.

Gender income inequality among workers is succinctly captured by the following: female workers earn only 63 paise for every rupee earned by male workers and the disparity in this regard is worse for Dalits and rural workers.

These structural barriers are compounded by regional disparities that have been exacerbated by the proliferation of the neoliberal project in India, with states in central and eastern parts of the country being pushed behind in terms of income growth. Thus, the persistence of poverty is both an economic and a socio-political problem.

When confronted with the empirical refutation of the previously mentioned process through which poverty reduction ostensibly comes about, some denizens of the neoliberal project argue that rapid growth in output enables tax revenue to rise. In turn, this higher tax revenue can be used to reduce poverty and make the growth process more inclusive.

However, this does not transpire since in the neoliberal phase of the capitalist system, the government emerges as a key site for the primitive accumulation of capital. This creates a political economy climate where the rise in tax revenue is less than adequate to deal with poverty reduction. In India, the denizens of the neoliberal project (as the representatives of the corporate-financial oligarchy) have stymied any meaningful debate on higher taxes on profits and wealth of the super-rich.

Therefore, the denizens of the neoliberal project make claims that poverty tends to spontaneously decline during the neoliberal phase of the capitalist system due to technological fixes usually digital technology. These proponents of the technological fix assume that the economy is supply constrained. The appearance and diffusion of the technological fix helps overcome the supply constraint thereby increasing the rate of growth. Further the extensive use of mobile phones ostensibly both reduced the cost of production and uncovered hidden sources of aggregate demand for enterprises in the unorganised sector. Consequently, incomes of those engaged in the unorganised sector will ostensibly rise above the poverty line resulting in a fall in poverty.

This fable about the technological fix that spontaneously reduces poverty is, however, invalid both in terms of empirics and theory. Let’s see how.

Nearly 48% of total households in India still lack access to the internet and there remain fundamental challenges regarding the diffusion of digital literacy among Indians. Besides, the share of smartphones (which enable the use of digital apps) in total number of phones used is not large since many Indians can’t afford to buy smartphones and pay the expensive usage charges (relative to their incomes).

Besides, there are issues about the relatively attenuated quality and coverage of the internet network in much of rural India. This is on account of the fact that internet service providers tend to provide relatively better quality and coverage of the internet only in urban areas where there is a threshold number of high- income persons and, therefore, buyers of their services. Thus, the claim that digitalisation by itself will diffuse to such an extent that it will reduce the cost of production for unorganised sector enterprises is empirically invalid.

Moreover, the proliferation of the neoliberal project has involved a steady loss of policy support to unorganised sector enterprises which has increased their cost of production to such an extent that digitalisation by itself (even if it is made available to a sufficient extent) is unlikely to reverse this increase.

Besides, the claim that digitalisation can uncover hidden sources of aggregate demand (and not merely demand switches) presumes that there is currently unmet demand for output produced by unorganised sector enterprises. It follows that this unmet demand would result in greater holding of money or financial assets by those whose demand is unmet. There is no evidence that there is any such accretion of financial assets and money in the hands of potential buyers of output produced by unorganised sector enterprises.

The other route whereby digitalisation could reduce poverty is through a digitalisation enabled demand switch from a relatively less labour-intensive output produced by organised sector enterprises to relatively more labour- intensive output produced by unorganised sector enterprise,

Once again, there is no evidence of any such switch transpiring. In fact gentrification of preferences under the rubric of the neoliberal project tends to work in the opposite direction along with the ongoing destruction of petty production due to the intensification of the primitive accumulation of capital.

In fact, digitalisation under neoliberal condition has allowed monopoly capital to encroach further into areas that were previously the preserve of unorganised sector enterprises. This has been the case whereby monopoly digital commerce companies have by and large extinguished the operations of large swathes of traditional (mostly but not exclusively petty) traders. Digital technology, in this context, is not the panacea it is often made out to be; rather, it is more likely to reinforce existing inequalities.

Poverty can be reduced only if incomes of all those who are below the scientifically determined poverty line can be sufficiently increased. This will require a meaningful combination of a universal employment guarantee (at or above the government mandated minimum wage) and universal income transfers (child support and elder support broadly defined) along with an expansion of the supporting infrastructure that has been severely undermined by the proliferation of the neoliberal project.

Currently, public health spending, which remains woefully inadequate at just 1.28% of GDP, has left India's healthcare system struggling to cope with the demands of a population of over 1.4 billion. The shortage of hospital beds, with only 0.5 beds per 1,000 people, was painfully evident during the pandemic, as hospitals were overwhelmed and countless lives were lost.

Similarly, public spending on education, at around 3% of GDP, falls far short of the 6% recommended by UNESCO, resulting in an education system that fails to provide quality learning for all. In other words, a reversal of this atrophy of social infrastructure is a necessary precondition for the workability of any alternative policy to reduce poverty.

Such a policy intervention because it is universal cannot, in principle, exclude the socially oppressed. But the implementation of these policies can certainly be undermined by the elites which can only be countered by political mobilisation.

The expenditure to put in place a universal employment and universal inform support that alone can eradicate poverty, can be financed by a combination a higher tax on profits and holding and inheritance of the wealth of the super-rich. Such a tax (on capitalists), which finances expenditure by the government (or transfer induced expenditure by its beneficiaries among the working people), will leave aggregate profits unchanged. If this larger aggregate expenditure increases the degree of capacity utilisation and, therefore, investment, as is likely to be the case, then aggregate profits will in fact rise!

Shirin Akhter is Associate Professor at Zakir Husain Delhi College, University of Delhi. C Saratchand is Professor, Department of Economics, Satyawati College, University of Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.