Hindi Imposition and the Impending Death of Regional Languages

A Hindi professor from a prestigious college in Delhi University once floored me with a question – “Saabji, yeh ‘Kannad’ Kahaan ki bhasha hai?” In a bid to educate, I pulled out the map of South India and told him about its major languages. “We had never been told about all this and we did not learn this in school either”, he regretted.

Under the hyped Three Language Formula (1968), nobody in the north of India was taught south Indian languages. Tamil Nadu did not implement the Three Language Formula but Karnataka did. Did Tamil Nadu stand to lose by not implementing it? Did Karnataka gain by half-hearted implementation of the Formula? Why is it that the North Indians don’t learn the languages of the South? – These are some of the questions the Union Home Minister Amit Shah needs to ponder upon before attempting to bring about “national integration” by imposing Hindi as the national language.

However, such questions have no place in the country’s present day discourse on languages. An accelerated use of Hindi is visible ever since the BJP-led NDA came to power in 2014. Official circulars, orders and office notes insisting on the use of Hindi are literally flying around the length and breadth of the nation. The effect of this has been the new but silent initiative to use Hindi wherever it was not used before. The notes introduced post-demonetisation have the value of the currency mentioned in the Devanagari script on them.. The use of Hindi is rampant on the road signs along National Highways across the country. The President of India Ramnath Kovind has given his consent to make Hindi compulsory till Class X in central government-run Kendriya Vidyalayas throughout the nation. In JNU, where I work, the text on my salary slip has changed from English to Hindi. All central government institutions like banks, post offices, railway stations, airports and home offices bear a strong presence of Hindi. All Central Government projects introduced since 2015 have Hindi names – “Atal Pension Yojana”, “Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameena Kaushala Yojana”, “Pradhan Manthri Bheem Suraksha Yojana”, “Jan Dhan Yojana” among others.

The Union Government spends generously on the implementation of Hindi. In 2009-10, 349 crores were spent on promotion of Hindi. In 2018, the then External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj announced that 400 crores would be spent if Hindi was made one of the official languages of the United Nations. In 2017-18, 43 crores were spent on increasing the reach of Hindi in foreign countries. For 2018-19, an outlay of 50 crores has been made for Hindi teachers in non-Hindi speaking states.

All these moves look like an imposition of Hindi on non-Hindi speaking states, but the Government defends it by saying it is the guidelines for “Official Language” as contained in Article 343 of the Constitution. On the strength of these provisions, the Union Government’s official transactions have predominantly been in Hindi. It has conveniently dropped the assurance of using English along with Hindi given by Nehru and Shastri in 1959.

There are historical reasons for north India’s pro-Hindi stance. Similar to howKannada-speaking areas came together under the umbrella of a unified Karnataka in 1956, north India, that lay scattered in more than 126 parts with different dialects, accepted Hindi as their common link language during the Indian freedom movement. The contribution of north Indian presses to this development was immense. Newspapers like Banaras Akhbar, Sudhakar Tatwa Bhodini, Saraswati, and writers and editors like Mahaveer Prasad Dwivedi, Balamukund Gupta, Ambika Prasad Bajpai, Chote Ram Shukla pushed aside local dialects to develop a ‘common’ Hindi ‘acceptable to all’.

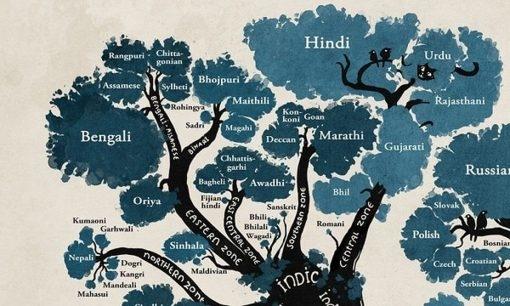

Pre-independence authors like Jai Shankar Prasad, Sumitranandan Pant, Ramdhari Singh Dinakar, Maithili Sharan Gupta, Makhanlal Chaturvedi, Bharatendu Harishchandra, Mahadevi Varma helped shape modern-day Hindi. This exercise steadily emaciated pre-Hindi languages like Braj, Awadhi, Rajasthani, Bafeli, Bhojpuri, Bundeli, Maithili, Chattisgari, Garhwali, Haryanvi, Kanauji, Kumauni, Magadhi, Marwari among others. Simultaneously, Persian, the language that was in ascendance during Mughal rule and Urdu, which had made great contributions to the freedom movement, also lost their prime postition. The communal void that surfaced during the Partition added to the chasm between Hindi and Urdu in twentieth century India. Communal forces of the time successfully established Urdu, a language spoken by a majority of North Indians, as the “language of Muslims”. However, how can one forget famous Urdu writers like B S Jain Jawahar, Ameer Chand, Bhagwan Das Ejaz, Sohan Rahi, Indra Mohan Deepak Kumar, Asha Prabhat, Kamini Devi, Rajendar Nath, Jayanth Paramar and others who were non Muslims?

Post-Independence Hindi tilted more towards Sanskrit to lose it’s connect with Urdu and established network with communal forces. It spread its wings and got closer to powerful leaders in Delhi. Non Hindi speakers started learning Hindi to please administrators. Bollywood movies and TV channels made Hindi popular. According to the 2011 Census, 52.83 crore people termed Hindi their ‘mother tongue’, which is 43.63% of the total population occupying first position among other language speakers in India. Such being the reality, it is no surprise that Hindi plays the role of a big brother.

The Indian National Congress (INC) trod the language issue with caution. INC had contemplated on the linguistic reorganisation of states way back in 1921. Hindi could not be made the “national language” even though Hindi speakers were pressuring for it to be declared so. Congress had to accept English temporarily for fifteen years to begin with.

While framing the Constitution, B R Ambedkar was plagued with confusion when it came to the language issue. Being a nationalist, he supported the linguistic reorganisation of states. In 1955, he reiterated that the danger of not re-organising states would be far greater than that of re-organising them. Yet, he firmly believed that a unified India, which emerged after a great struggle, should not be divided on the basis of language. Hence, he agreed to Article 343 which allowed the Union Government to use Hindi as the language of administrative transactions – “The Official Language of the Union shall be Hindi in Devanagari script”. However, he never declared Hindi as the “national language”. Instead, he declared all languages listed under the VIII Schedule of the Indian Constitution as equal.

Nehru, who was aware of the complexity of the issue, escaped the onslaught of the southern states by declaring that both Hindi and English will remain in use until 1965. Fearing that Hindi would become the national language after 1965, Tamil Nadu spearheaded an anti-Hindi agitation in late 1930s. Alarmed that the agitation would spread to other states, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri cited Nehru’s promise and declared to continue the use of English on popular demand. The decision was seconded by Congress. Yet, the Union Government has cleverly continued with the hidden agenda of promoting Hindi. Whenever these tactics are exposed, the Union Government considers the resultant resistance very seriously and find alternate ways to follow its agenda. Meanwhile, the present Union Home Minister has declared that Hindi should become the “national language” representing India. A move he believes would result in national integration.

‘One Nation, One Language’ is also an idea that the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) goes by. It looks as though RSS aims to declare Hindi as the “national language” by 2025 – its centenary year. The task doesn’t seem to be difficult for the present government when we observe its linear approach to issues. This goal could be achieved soon enough considering how the Parliamentarians representing Kannada in Delhi have often sided with the Union Government and Hindi. They have not even upheld the constitutional provision made for modern Indian languages as per the VIII Schedule of the Indian Constitution (1967). If Hindi is declared the national language of India, the 19,569 languages listed in the People’s Linguistic Survey of India will suffer a slow death. The Survey lists about 40 languages with more than 10 lakh speakers, 60 languages with more than 1 lakh speakers and 122 languages with more than 10 thousand speakers. Moreover, there are 99 more languages waiting to be recognised by the Constitution for an entry into the VIII Schedule. Sadly, the Union Government has no plan of action to strengthen these languages and the Home Minister has no time to pay attention to these languages.

India, which is home to more than half of the world languages, doesn’t have a suitable language policy. This lacuna makes it easier to play with languages. Even though only 24,821 people listed Sanskrit as their mother tongue , the Union Government has accorded it pride of place in its language-related policies. The same government has shown no interest to add Tulu, with its 50 lakh speakers, to the VIII Schedule. When all other languages come under the Human Resource Ministry, Hindi remains with the Home Ministry. This is a terrible situation for sure. We stand as mute witnesses to the tragedy of languages and the separate worldviews they offer moving towards death.

A party that boasts of taking the country back to the glory of its ancient past harks on one language in a multilingual country! Academicians would know that this idea of a single national language is borrowed from the West. Ancient India approached languages differently. The colonial impact on our thought process is nowhere more visible than in our government’s approach towards language.

If only the non-Hindi states could bury their differences, come together on a single platform, fight against the imposition of Hindi and simultaneously, formulate an inclusive national language policy, there would be some hope for stalling this impending tragedy. This is easier said than done.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.