Gujarat Elections: Kutch’s Barren Banni Grassland Graveyard of Hopes, Dreams

At the center of Udai village in Eastern Banni

Banni, Kutch: At the end of the road, where the 15 km journey to the villages begins, lies one of the Panchayat offices with leaking and cracked walls and a shut Ayushman Bharat Kendra.

Welcome to Banni ‘Grassland’, a vast expanse of barren land in Gujarat’s Rann of Kutch that is home to around 22 ethnic groups with a population of around 40,000. Every settlement is miles away from another.

Around 90% of the population is Muslim and the rest are Scheduled Castes, mostly the Marwads. The region falls in the Bhuj Vidhan Sabha Constituency though Bhuj is around 100 km away from these far-off villages.

Banni is the graveyard of dead hopes and dreams with its pastoralists in a permanent state of migration and trading dung for water to save their cattle and themselves.

These voters still survive on the barter system in Digital India. In a month or so, the region would become dry and they will be forced to migrate again. Subsequently, the grind to find a no man’s land, settle there along with their cattle and find a kind farmer who would agree to provide them water in exchange for buffalo dung—which is a good fertiliser—would begin.

In the rear corner of western Banni, there are four villages mostly inhabited by Jat Muslims. “If they [cattle] survive, we will. Since we have water only for four months, we are compelled to migrate for the rest eight,” says 52-year-old Sadik Maluk, a native of Sarada village, as he chews tobacco on a charpoy amid buffaloes, dung and a swarm of flies.

Migration is not easy either. “It costs Rs 20,000 if we take our buffaloes along. Since we do not have that kind of money, we sell nose rings of our women,” he adds.

Maluk’s description of the backwardness of the region is like travelling back in time. “As one crosses each settlement, the living conditions get worse and it is like going back 50 years even when compared with rural areas.”

Backwardness is part of their society with women supressed and relegated to chores. “Our culture does not allow this. They aren’t allowed to speak with men,” he says when the reporter requests him to allow his women family members to speak on migration.

“Women of the house cannot go out unless absolutely necessary, cannot watch television or use the phone or even study post the 8th grade. If a woman wishes to speak with our women, we will allow that, but not a man,” adds Maluk.

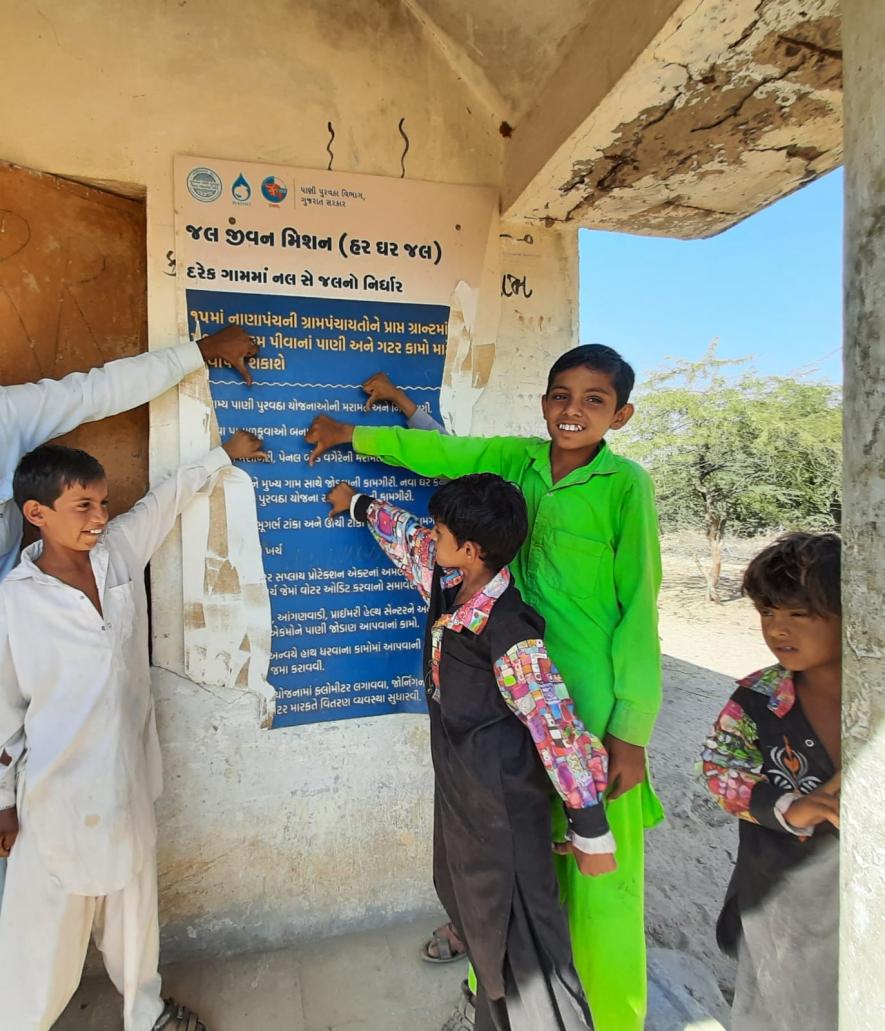

As one moves towards eastern Banni, water scarcity acquires a symbolic irony. Udai, one of the last settlements where most of the inhabitants are shepherds and breeders who lead a nomadic life in search of water, has a board displaying the words ‘Har Ghar Jal Yojana’ right outside its Panchayat office. However, villagers still use wells that last for only four months since the board was installed a year ago. All the water tanks constructed 15 years ago are dry.

Kids at Udai village explaining how the 'Har Ghar Nal' Yojana was restricted to the Board intact outside their Panchayat office. There is not a single tap connection in their village.

Illiteracy is rampant with families migrating for, at least, four months a year and the schools in a sorry state. At the primary school right outside Maluk’s land, only one out of three classrooms were accessible. There were hardly 10 students of different age groups and three teachers. The teachers often find it difficult to communicate with the students and manage them as none of them belong to Kutch or know the local language well.

When asked about the low attendance, the teachers mentioned several problems. “Parents often don’t send their kids to school saying that they would ultimately become breeders. Besides, the school is unhygienic,” says Savita, a primary teacher in Sarada village.

With villages like Udai not even having a school, around 600 children in the region don’t have an option but to get enroled in the local madrasa.

The 15 km dusty unmetalled road to eastern Banni villages speaks of government neglect and apathy. The villagers recall the sitting MLA, Nimaben Acharya, visited their villages in earlier election campaigns and promised a metalled road, education and healthcare. However, neither she nor the sarpanch ever visited them since then.

In fact, Acharya was the only public representative to have ever visited the region. During most election campaigns, not even Zila Panchayat members bothered to contact the villagers though they expected them to vote.

Amin Changa (40), from Udai, explains why the villagers still vote and hope for a change. “We vote for two reasons. First, we feel voting for one person will make him/her fulfil the promises. Second, if we do not vote, a candidate will still win since Bhuj voters would vote only for the BJP. Therefore, if we don’t vote, the winning candidate will not even think of solving our problems.”

One of the biggest problems of Banni is the absence of healthcare. The Ayushman Bharat Kendra in Sarada, according to villagers, has been closed since its construction more than two years ago. Villagers in eastern Banni have a similar story to narrate.

“When we dial the 108 Seva (service) emergency number, a person arrives but often too late. We travel to Bhuj, which is around 100 km away, to receive immediate help in a medical emergency. Even then we often fail to reach on time due to the poor condition of the roads,” says Amin adding that they “cannot even recall the number of villagers who have due to the lack of healthcare in the past five years”.

The lack of roads even confuses the locals while navigating their way in eastern Banni’s last settlements. A long deserted road leads to the Panchayat office, which has been apparently cleaned up to be used as a polling booth in the Assembly polls. However, the cracked walls were leaking, the floor and roof were dirty and one of the rooms was stocked with hay.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is known to have revolutionised Banni region with the ongoing Rann Utsav. However, the ground reality in western and eastern Banni is completely different compared to the central region, where villages like Dhordo resemble more of a township.

A look-alike Ayushman Bharat Kendra outside Dhordo(a village that comes on the way of the visitors to Rann Utsav), completely operational.

A lookalike of the Ayushman Kendra in western Banni is operational. Though the doctor was not present, two assistants were available for help with the centre open 24X7 and accessible to all the nearby villages.

The freshly whitewashed Panchayat office, two ATMs right outside the office, parked cars, a park for kids and a proper police station present a contrasting picture.

The ‘revolutionised’ village model is meant to impress outsiders. On the other hand, the hopes and dreams of the neglected side of Banni die during every election season.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Delhi and is travelling to Gujarat to report on the Assembly elections.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.