Governing the Tongue

There is a virus that seems to be going around. So rampant is this virus that it has infected even the state which once upon a time thought of itself as the mai-baap of the people.

This virus ensures that its host cannot tolerate dissent of any kind. All views other than those from its small, official (and self-serving) window suddenly become anti-national, obscene, or a threat to law and order. State censorship in its aggressive mode can be exercised in all kinds of ways, from phone-tapping to banning books, films, plays and art that try to enlarge the state’s one-eyed vision. And in its passive-aggressive manifestation, the government looks the other way when goons – whether from the Shiv Sena, or the Ram Sene, or the Bajrang Dal or any other self-appointed “army” – routinely beat up people and vandalise public and private property because these tender-hearted goons get hurt very easily.

The latest battlefield is the internet – a strange world where all kinds of anonymous people live, but also a place where individuals and groups of citizens can speak out and hold debates. This possibility provides a valuable alternative to a mainstream in the grips of state and corporate control.

But this is precisely the sort of space that the powers that be cannot leave alone. The Indian Telecom Minister recently made a move toward government screening of content on social networking sites. In his article “At the Crossroads of Mediaphobia” (Hindu, January 30, 2012), Amitabh Mukhopadhyay makes a telling comment about the Minister’s triple-speak. Mukhopadhyay says, “The shifting sands of (the Minister’s) reasons for objecting to certain matter carried on social media are interesting. Apparently, he found a page maligning Sonia Gandhi and told Facebook officials… this was unacceptable. He then wrote a letter and held meetings with Google and Facebook. In an interview on NDTV… he said he objected to pornographic images. Then there was a mention in newspapers that at a press conference… he was worried about things that hurt religious sentiments.” Clearly the Minister has trouble making up his mind; but his intention – and those of his masters – is crystal clear.

The next move has been to make sure there is no tweeting an “Indian Spring”. In this case, the micro-blogging website Twitter seems to have anticipated the desire of censoring governments. Twitter has proposed that it will withhold tweets in a specific country when there is a “valid request” from a “legal authority”. We are yet to see how this will develop, but one thing is apparent. Not only do internet giants have trouble standing up to government pressure; they are also willing to fudge freedoms on the net in exchange for greater business opportunities.

But we don’t live on the net all our waking lives. We also talk to each other in meetings and seminars and refine our positions on various vexing issues; we learn and teach in a classroom, the place where we should hone our critical skills; we live in a neighbourhood and a larger society in the mosaic called India.

Police and other volunteers take injured dramatist Habib Tanvir to a hospital after he was injured by the activists of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the student wing of the BJP. AP PHOTO/AJIT KUMAR, OUTLOOK, JUN 13, 2005,

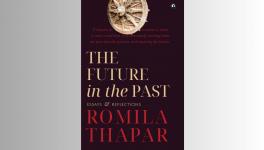

What animates this mosaic and gives it a soul? A thing called culture – increasingly an arena of dispute, and also a victim of the government’s passive- aggressive strategy. The guideline seems to be to stand by and let the jungle-policing-raj play out its predictable script – so that anyone can become an expert overnight on literature, art, philosophy, film, theatre. And when these experts come face to face with the real world in all its heterogeneous complexity, what do they do? Get hurt. They ban books, films, plays; they harass a Husain or a Rushdie. (It is important to remember that for every famous case, there are a hundred others that do not make the headlines or provoke “debates” in the media.) Christian fundamentalists take on Paul Zacharia; Muslim fundamentalists become unhappy poetry readers when they dig up an old couplet by Mohammed Alvi. As for Hindu zealots, they are absolute workaholics. They quarrel with Sunil Gangopadhyay and H.S. Shivaprakash, or they find Habib Tanvir’s plays offensive. In between, academics like Romila Thapar, Sumit Sarkar, K.N. Pannikar and James Laine and acclaimed journalists like Joseph Lelyveld are given crash courses in Indian History 101.

Which brings us to perhaps the most dangerous aspect of this allergy to multiple views. This is the policing of academic spaces – spaces that are meaningless if they do not actively promote learning how to debate through words, film and art; through imaginative speculation and reconstruction. We are in a strange situation indeed when a university syllabus can be decided on the basis of fear, of “law and order situations”, or the “political”.

Students and teachers of Delhi University stage a protest demanding re-introduction of scholar-poet A.K. Ramanujan's essay on the Ramayana. File Photo: R.V. Moorthy The Hindu, October 25, 2011,

There is the Ramanujan example, particularly poignant because the fuss in Delhi University was about an essay that talks about the rich rewards of recognising that multiple views interact to produce a dynamic cultural system. Ramanujan’s essay talks about the ways in which tellings and retellings, oral and written, epic and tale, relate to each other. They do it, he writes, in ways that impoverish a part – one story or tradition or genre – if it is mistaken for the whole. The grand saga of the epic has to be viewed along with its homely versions, folk tales and traditions that cut sagas down to size for daily consumption. Love, death, incest, the afterlife – nothing is too big or subtle for the debate conducted among these tales, and between this earthy body of tales and the more revered “classical” texts and traditions. Acknowledging the familial relationships among all the possible types of tellings means reaping a reward of a large and amorphous body of systems, counter-systems; traditions, alternative traditions; tales and counter-tales, private and public lore, a body that can never quite be complete as long as people continue to complete the telling for their times and lives. Perhaps the biggest gift Ramanujan the go-between has given us is showing us how important it is for culture to travel; to give and receive.

Whether it is an essay or a novel or a film, the university syllabus, classroom and seminar have become disputed sites. The latest example is the fear of politics in a seminar planned by Symbiosis University – more specifically, the fear of a film on Kashmir by Sanjay Kak. The University management has given in to the demand of several right-wing organisations that the film not be screened during a seminar on “Voices of Kashmir”. The film, they say, is “separatist”. As of date, this is the situation: the seminar has been postponed indefinitely. The Symbiosis Founder-Director has said they will “revisit and rethink” the content of the seminar and make it “more balanced”. The Principal of the College of Arts and Commerce has made some extraordinary statements (Hindu, January 31, 2012): “The organisations felt that the event should be more inclusive. We do not want any unnecessary controversy. If these people are so passionate about the issue, then there must be some valid reason. We, as academicians, want to listen to their views and respect them.” To make things worse, he says, “An educational institution is not a proper forum, a platform, to discuss this. If the seminar turns political, we will stop it immediately.”

He does not add the obvious: that respecting the views of the cultural police, and being allergic to the “controversial” or the “political” means you cannot have a seminar on Kashmir at all. You don’t have to be an “academician” to know that life in Kashmir is inextricably bound with the presence – and absolute power – of the army. How then can anyone have a seminar – or write something or film something – without facing this fact squarely?

What happens when we deny, time and again, the necessity of living as thinking, speaking people? We cannot have a free media; we cannot have educational institutions that actually promote teaching and learning; we cannot have artists who help us see the world in new, more perceptive ways; and we cannot have citizens who are allowed to see that truth is a complicated thing, that it needs to be thought through and argued out every single day. Most of all, we cannot make use of our common sense. Common sense says diversity of views should simply be allowed to remain diverse; and dissent should remain dissent, so that we may look for truth in all its forms, however uncomfortable some of it is.

The South African writer Andre Brink puts it eloquently: all significant art, he says, is offensive; offensive in the sense of striking against; opposing; revealing; resisting. Not just resisting the siege, but also breaking down the resistance in the reader. The writer’s (or filmmaker’s, or teacher’s) opposition exists in a peculiarly agonizing form in times of siege: awareness of the intolerable condition of his world. John Berger says: “Our torture is the existence of others as unequals.” And with our information technology, no one, and certainly not a thinking citizen, can claim he has not seen the intolerable condition of his world. The besieged artist – and citizen – has no option but to continue making maps of the world; not duplicating the world itself, but creating one map after the other of what she sees must be exposed, understood and changed.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.