Funds Crunch Hits India’s Anti-Malaria Fight

Image Courtesy: Financial Express

On World Malaria Day, it looks like the global fight against malaria is faltering with number of cases increasing by about 5 million to reach 216 million cases in 2016 and the global death toll remaining stagnant at about 445,000, according to World Malaria Report 2017 prepared by WHO. It stresses that funding constraints are leading to the slowing down of efforts to control malaria.

What about India? There has been a sort of celebratory mood among policy makers because cases reported and deaths recorded have been steadily declining going by official records. This mood was further energized when Prime Minister Modi, true to his style, declared on an international forum that India will eliminate malaria by 2030. Towards this, a ‘new’ National Framework was announced in February 2016. This was followed by a National Strategic Plan, 2017-2022 and then an Operational Manual for Malaria Elimination in India was also released.

The priority given to malaria elimination is needed. About one in three Indians live at risk with malaria infection because mosquitoes infest the bulk of the country, especially Central India and the North-East. The Lancet had estimated that at least 50,000 people died of malaria in India in 2010 not just a thousand as officially reported. It is estimated that about $2 billion is lost every year due to malaria, mainly on account of work-days lost.

But there is a major – a fatal – handicap to the govt.’s grand plans. The Modi govt. is not willing to spend money on implementing the programme. If there is limited sub-optimal funding then the best laid plans are doomed to failure.

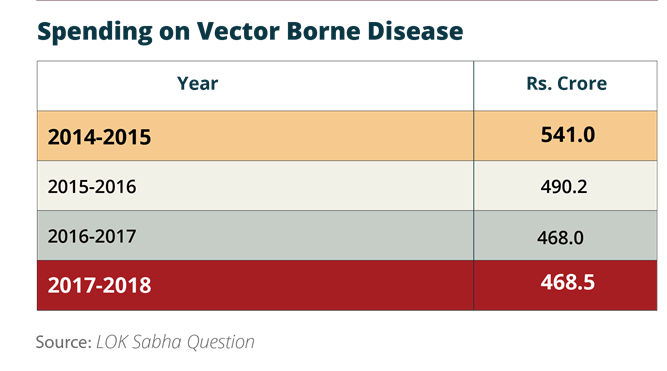

A recent query in the Lok Sabha (#107 on 9 Feb 2018) on how much spending is being done on the National Vector Borne Diseases Control Programme (NVBDCP) under the health ministry elicited a response from the health minister J.P.Nadda where he revealed that annual fund allocation for this key programme had declined by 13% between 2014-15 and 2017-18. In 2014-15, when the present Modi govt. took over, Rs.541 crore were allocated for this programme that is charged with control of all vector borne diseases including malaria, dengue, chikungunya, Japanese encephalitis, filariasis, etc. In 2017-18 it stood at Rs.468.5 crore.

Studies have shown that in India, the bulk of the spending of malaria control efforts is devoted to administrative costs, salaries and other expenses rather than on mosquito nets, medicines and insecticidal sprays. So, the reduced spending becomes all the more ineffective.

It has also been found that distribution of Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLIN) – considered one of the most effective ways of protection against mosquitoes – has been very limited. Under the UPA regime, auctions were cancelled twice and $200 million was returned to World Bank without any LLINs being purchased. Now, it is reported that since 2014, some 12.4 million nets were purchased and another 5 million in the pipeline by 2016. The estimated need of such nets is about 250 million.

With this approach, the possibility of eliminating malaria becomes rather dim and all the declarations mere rhetoric.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.