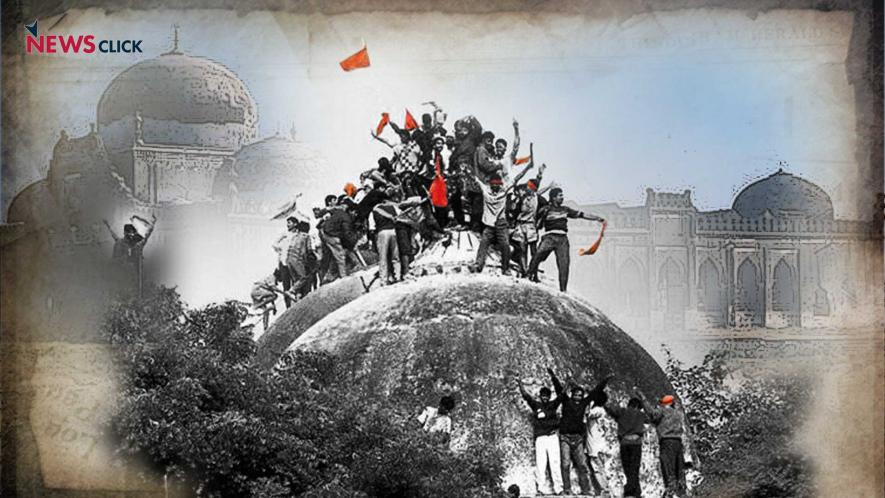

From Parochial to National: The Rise and Rise of Ram Janmabhoomi Movement

The Ram temple issue has been at the epicentre of Indian politics since the mid-1980s. The resolution of the ‘mandir or masjid’ question in the Mandal-era was apparently executed when the Supreme Court delivered its judgement on November 9, 2019. The 5-member bench in a unanimous verdict gave the ownership of the 2.77 acres of disputed land to the Ram Janmabhoomi trust and ordered it to build a temple on the site.

In Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay’s new book ‘The Demolition and the Verdict’, he writes that the SC judgment on Ayodhya civil case raised eyebrows as the five judges were in almost complete agreement. Mukhopadhyay then looks into the genesis, and especially, the second coming of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement from the early 1980s, in order to understand the larger project of Hindutva forces in ‘reconfiguring’ the Indian republic. Much of this centred around extending the limits of what was in the 1950s only a minor and parochial issues, to one that became a national agenda by the 1990s. Some excerpts from the new book:

India awoke on 20 February 1981 with the stunning news of mass conversions of nearly 800 Harijans to Islam in an obscure village called Meenakshipuram in Tirunelveli district, Tamil Nadu. The event permanently etched the village’s name in the annals of Indian political history and was the result of continued harassment of Dalits by the upper castes. The village not only had separate drinking water wells (for Harijans) but also ‘three tea-stalls at Panpoli (a bigger village nearby) run by a Moopanar, a Thevar and a Muslim. Harijans can get tea at a shop run by the Muslim but not from the other two stalls.’

A state government report stated: ‘From the discussions with the converted Scheduled Castes it was obvious that a longstanding social discrimination based on untouchability and indifference of Hindu society at large towards them was the major cause for the conversion.’ Yet, instead of examining the causes which triggered these conversions and preventing continued ostracisation of the Scheduled Castes across India, several groups alleged ‘conspiracy’ and ‘Gulf money’.

Even the Union home ministry doled out data selectively, suggesting that conversion had not been a one-time affair, but was going on unnoticed for more than a year. Accusations of a ‘foreign hand’ behind the conversions were made by a diverse lot—from Tamil Nadu chief minister, M.G. Ramachandran, to the RSS.

After a visit to the village, a VHP team claimed that ‘temptation for financial gain and assurance of protection from police appear to be the main reasons for conversions in Tamil Nadu’. The RSS promptly began reconverting these Harijans. Ironically, the RSS campaign emphasised on ‘conspiracy’ and not on the ‘unfulfilled task’ as spelt out by Deoras seven years ago at Poona. Lower castes were being discriminated against and the result was there to see. This reflected not just the duplicitousness of the RSS, but Deoras’s inability to get his organisation on board apropos his reformist idea.

Outside the RSS fold, many non-affiliated Hindu religious leaders took independent initiatives to embrace Harijans. For instance, at New Delhi’s Lakshminarayan Mandir, 100 Harjians were anointed as priests in August 1981. In Meerut (UP), the local Arya Samaj body conducted a yagna in a colony inhabited mainly by Jatavs, a Harijan subcaste. More importantly, Swami Karpatri, one of the most orthodox Hindu preachers in north India and who was consulted prior to the installation of the idol in Ayodhya in December 1949, asked for removal of every restriction on Harijan pilgrims at Varanasi’s Kashi Vishwanath temple.

Still, instead of campaigning to end caste-based segregation and maltreatment, the RSS stuck to the ‘influence of vast amounts of money, coercion and such illegal and antireligious methods’. It alleged that ‘Muslim proselytisers’ had given the ‘lure of so-called equality in Islam’ while making ‘promises of security in the Muslim fold because of political favouritism and dangling of lucrative jobs in oilrich Muslim countries’. The Meenakshipuram incident, however, provided the RSS with the perfect opportunity to fortify the Hindu community and stigmatise Muslims (and Christians). Deoras directed the VHP to post-haste mount a nationwide campaign against mass conversions. Several other anti-conversion initiatives too were kick-started in Tamil Nadu, namely, the Hindu Ottrumai Maiyum (Centre for Hindu Unity) and the Hindu Munnani (Hindu Front). These publicity and mass mobiliastion drives secured widespread support as reflected in the Hindu Munnani candidate winning a Tamil Nadu state assembly seat in 1984 from Padmanabhapuram, former capital city of the erstwhile Hindu kingdom of Travancore.

The incessant Sangh Parivar campaign against religious conversions, especially the Meenakshipuram incident, coincided with a spurt in communal incidents since the beginning of the 1980s. Social scientist Ashutosh Varshney, who tracked communal violence and riots in India over a forty-five-year period from 1950 to 1995, recorded a spike in the number of deaths in communal incidents from the beginning of this decade. In north India, between mid- August and November 1980, ‘Muslims in Moradabad experienced the most bloody orgy of violence’. The 1980s was the decade when religion emerged as a major factor in electoral politics and statecraft. Indira Gandhi eyed the emerging political Hindu. She began by enlisting this constituency to her party’s benefit during the Jammu and Kashmir assembly elections in 1983.

If these developments firmed up a political launch pad for the Sangh Parivar, the year 1983 marked the genesis of the agitation for the Ram temple at Ayodhya. At that time, however, no formal announcement was made of a plan that would, in time, raise a framework within which the Indian political discourse is now conducted. Paradoxically, the first steps to revive the Hindu demand for the Ram temple, which lay forgotten in public memory after the initial enthusiasm of the early 1950s, were not taken by the RSS, but by two former Congress leaders. The proposal to put it on the national agenda was first mooted by Daudayal Khanna, an ageing one-time UP minister.

In May 1983, he wrote to Indira Gandhi asking for the restoration of not just the Ayodhya temple, but even the two in Varanasi and Mathura. He also met cabinet minister in the Union government, Kamlapati Tripathi, who ‘told him that they [Khanna and his associates] were trying to ignite barood [gunpowder] and Congress policy of Hindu-Muslim unity will lose its significance’. Barely weeks prior to Khanna despatching his letter, Gulzarilal Nanda, one time Union minister who also acted as interim prime minister for two short durations (after the deaths of Nehru and Shastri), founded the Shri Ram Janmotsav Samiti (Society for the celebration of Shri Ram’s birth anniversary) on the occasion of the festival of Ram Navami (the date according to the Hindu lunar calendar that is believed to be the day when Ram was born).

To mark the occasion, Nanda hosted a feast, as traditionally organised during such festivals. He also succeeded in gathering leaders from several organisations, including the RSS. The BJP White Paper on Ayodhya released in 1993 states that the movement was ‘conceived’ at a ‘meeting at Muzaffarnagar, attended among others by the former Union Home Minister Gulzarilal Nanda and Professor Rajendra Singh [he became sarsanghchalak after Deoras relinquished office] of the RSS, [where] the question of the liberation of Ram Janmabhoomi was raised by Shri Daudayal Khanna’.

With the advantage of hindsight, it is evident that several initiatives were taken almost simultaneously and these arose from the Hindu disquiet over the Meenakshipuram conversions. Yet, the RSS did not devote its energies to the demand for the Ram temple immediately. This was due to two reasons. First, the RSS and VHP were already working on a plan to mobilise Hindus nationally with a programme emphasising religious identity. The programme, given the name of Ekatmata Yatra (literally one-soul pilgrimage but essentially conveying oneness among Hindus), used elements of yatra (religious pilgrimage) and Hindu iconography involving two powerful symbols—the River Ganga and Mother India—as objects of divinity.

In this programme, preparations for which were made through 1983 before its launch on 16 November, the VHP partnered with Karan Singh’s outfit. This programme mirrored Deoras’s viewpoint that the RSS world view should eventually become part of daily social discourse of the ‘samaj’ or society, or as they often say ‘sangh hee samaj hai’ (RSS is the society and vice versa). Lavishly mounted, the yatras drew unprecedented crowds. Chariots carried giant urns with water from rivers considered holy by Hindus.

The second reason why the RSS did not immediately follow up on either Khanna’s missive to Indira Gandhi or Nanda’s initiative and the meeting at Muzaffarnagar was that the leadership was unsure of the resonance the Ram temple issue would have. They were uncertain if the issue would be a big draw among all sections of Hindus because different sects deified diverse gods. By the late 1950s, the RSS had emerged as the principal Hindu nationalistic outfit, as the Hindu Mahasabha had been marginalised.

The Ram Rajya Parishad founded by Swami Karpatri no longer featured in the race for the support of the Hindu constituency after winning some assembly seats in Hindi-speaking states in 1957. A resolution adopted by the Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha of the RSS in 1959 was indicative of the organisation’s prioritisation of the Ram temple issue. This extremely significant document, rarely noticed, was the first in which the RSS formally adopted a position on ‘temples converted into mosques’ by ‘intolerant and tyrannical foreign aggressors and rulers in Bharat’. Titled, ‘Issue of Temples Turned into Mosques’, the resolution did not mention the Ayodhya shrine and limited a direct reference to the Kashi Vishwanath temple in Varanasi. The RSS falsely claimed that ‘an intense desire to resurrect these places of worship was ever present at the heart of the freedom movement’.

It accused independent India’s government of remaining ‘totally callous to the legitimate rights of the Hindus over such temples’. For the RSS these shrines were a ‘reminder of the continuing foreign aggression’ and that it was ‘but natural that discontent among Hindus will remain acute’. Non-restoration of these ‘temples’ to Hindus would not make it ‘possible to bring about emotional integration of the Muslims with the main [sic] national society of the land’. The RSS demanded that the government, guided by the ‘view of creating an atmosphere of mutual tolerance and goodwill, should take steps for the return of all such desecrated temples and ensure their renovation’. Only the Varanasi temple was mentioned as holding an ‘unique position as the centre of devotion and faith of all Hindus throughout the country’.

The Demolition and the Verdict: Ayodhya and the Project to Reconfigure India by Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2021.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.