DU: CCS-Based Periodic Review a Threat to Academic Freedom

The Executive Council of the University of Delhi has decided to examine the extension of the system of the Central Civil Service Rules (CCS)-based periodic performance review of Union government employees to teachers. If this is adopted then it will bring into effect the provision for compulsory retirement to teachers too.

This consideration, if implemented by the University of Delhi, would amount to a ‘de facto’ extension of CCS rules to teachers. Such a move would undermine the foundational principles of university autonomy, academic freedom, and the distinct legal and organisational frameworks governing higher education institutions as opposed to government organs.

This move, ostensibly aimed at enhancing administrative efficiency, is fraught with legal inconsistencies. It also threatens the intellectual independence crucial to academia and misapplies a policy instrument supposedly designed for government employees to an environment where the dialectic between tenure and critical inquiry is paramount for the emergence of socially productive academic outcomes. By seeking to impose academic precarity through mechanisms purportedly intended for Union government employees onto university teachers, the administration of the University of Delhi risks eroding the very ethos that sustains scholarly excellence and institutional integrity.

Legal and Procedural Flaws

The statutory autonomy of universities in India, including the University of Delhi, is enshrined in Acts of Parliament that establish these institutions as self-governing entities. These Acts empower universities to formulate their own statutes and ordinances. Under the umbrella of the Regulations of the University Grants Commission (UGC), the service conditions of teachers are set out. The involvement of teachers in the academic environment is shaped by how this interplay of UGC Regulations and the Act, Statutes and Ordinances of each university is tailored to the unique demands of the socially relevant academic tasks of that university. Thus, there is a logical rationale for the distinction between the work environments of government employees and teachers.

The move towards the ‘de facto’ imposition of CCS rules, formulated only for Union government employees, disregards the legal separation that has the aforementioned logical rationale as its basis. Government employees operate within a hierarchical structure seemingly focused on administrative efficiency and public service delivery. But universities function as autonomous organisations mandated to foster critical thinking, research, diversity and pedagogical innovation, all of which are logically antithetical to hierarchy. For instance, the head of a department in universities is appointed on the basis of the principle of rotation by seniority, which is not the case in the government.

This procedural lapse not only violates the university's governance protocols but also sets a dangerous precedent for extra-legal external interference in academic affairs.

Moreover, the legal framework governing Union government employees and university faculty is fundamentally distinct. CCS rules, including provisions for compulsory retirement under Fundamental Rule 56(j) and periodic performance review, are allegedly rooted in the objective of the government to maintain administrative efficacy and integrity within governmental machinery. However, universities operate under separate regulations, such as the UGC's regulations on academic service conditions, which rationally emphasise the dialectic between job security and intellectual freedom to safeguard against irrational political or administrative pressures, thereby advancing the social objectives of innovation, diversity and inclusion.

The ‘de facto’ assimilation of CCS rules into university governance conflates these divergent objectives, effectively subordinating scholarly priorities to hierarchical imperatives that have little to do with academics. Such an overreach, besides lacking legal validity (as previously argued), also contravenes the principle of institutional autonomy upheld by judicial precedents and parliamentary statutes.

According to CCS 2(h):

"Government servant" means a person who -

(i) is a member of a Service or holds a civil post under the Union, and includes any such person on foreign service or whose services are temporarily placed at the disposal of a State Government, or a local or other authority;

(ii) is a member of a Service or holds a civil post under a State Government and whose services are temporarily placed at the disposal of the Central Government;

(iii) is in the service of a local or other authority and whose services are temporarily placed at the disposal of the Central Government;

The High Court of Allahabad in its judgement 2015:AHC:50411-DB dated 19.3.2015 had stated in a matter concerning Allahabad University that: "The Professors of the University are neither members of a service nor do they hold a civil post under the Union nor are they in the service of local or other authority. CCS(CCA) Rules would, therefore, have no application to a Central University".

This implies that any attempt to bring teachers of a Central University, such as the University of Delhi, under the rubric of CCS rules, either in full or in part (provision for compulsory retirement and periodic review of performance), will violate the High Court judgement.

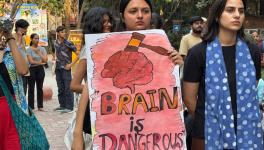

Blueprint to Abridge Academic Freedom

Academic freedom—the liberty to pursue research, question orthodoxy, and engage in unfettered intellectual discourse—is a critical cornerstone of education. The plan to introduce compulsory retirement and CCS-based periodic performance review provisions for teachers jeopardises this freedom by introducing a culture of precarity and conformity. It has been a practice in the government to undertake periodic reviews to identify "deadwood" ostensibly to serve administrative efficiency. But in academia, where intellectual contributions often evolve over years if not decades, such mechanisms for compulsory retirement and periodic performance review are inherently misaligned with the dynamic trajectory of socially relevant scholarly pursuits in the domain of research and teaching.

Senior faculty members, with their wealth of academic experience, play pivotal roles in mentoring students and younger faculty, being constructive custodians of institutional memory, shaping curricula in nuanced ways, and advancing socially relevant research and innovation. Subjecting them to arbitrary reviews based on age or tenure undermines their ability to contribute meaningfully, fostering an environment where job security hinges on compliance with irrational protocols rather than academic rigour and innovation.

Furthermore, the spectre of compulsory retirement and periodic review of performance could be weaponised to suppress dissent or critical perspectives. Universities thrive on diverse viewpoints and constructive debate, essential for addressing complex social challenges. If faculty members apprehend premature termination for espousing heterodox opinions or challenging non-constructive institutional policies, self-censorship will become inevitable. This chilling effect will stifle innovation and reduce academia to a technocratic appendage of the government, resulting in an attenuation of democracy.

The conflation of administrative efficiency with academic outcomes, as implied by CCS-style reviews, also risks prioritising narrow and quantifiable metrics that are academically irrelevant over substantive intellectual contributions that often defy any routine quantification. Research breakthroughs, pedagogical impact, and interdisciplinary collaborations are often intangible when evaluated through bureaucratic metrics. Undermining India's academia will put paid to any possibility for the Indian economy to meaningfully negotiate an authentic ascent of the technological ladder that pertains to global production networks.

The provisions for periodic performance review and compulsory retirement can also be used to attenuate diversity by selectively targeting teachers endeavouring to uphold disciplines that are socially necessary (Indian languages) but may not always be resource spinners in terms of fees.

Likewise, the provision of compulsory retirement and periodic performance review can be used to selectively target teachers from socially oppressed communities, especially in contemporary India that has seen vigorous efforts to halt or reverse social justice. This would amount to a nullification of reservation by stealth that is analogous to the abortive attempt to further lateral entry of elites from the private sector into the government.

Moreover, periodic performance review followed by compulsory retirement can be used as a neoliberal tool to minimise pension payout. Teachers appointed since 2004 are part of the defined benefit National Pension Scheme. The earlier the date of retirement, the lower will be the government contribution that will need to be made to the retirement corpus of the compulsorily retired teacher. Furthermore, the unified pension scheme or UPS has not yet been extended to teachers. If it is extended to teachers, then deliberately engineered early compulsory retirement can lead to no or reduced pension payout.

The shift toward contractual employment, tacitly encouraged by neoliberal policies, of which compulsory retirement and periodic performance review are key components, exacerbates these concerns. Replacing tenured positions with contractual roles undermines job stability, discourages long-term research commitments, and tends to demotivate the academic workforce. Contractual staff, dependent on short-term renewals, may be compelled to prioritise immediate deliverables over pioneering scholarship, thereby eroding the university's intellectual prowess. Without persistent furtherance of this intellectual prowess, the quality of immediate deliverables and their academic outcomes will tend to deteriorate over time.

This adverse trend aligns with broader attempts to commercialise and increasingly privatise education, where short-termist microeconomic cost-cutting measures supersede rationally long-term public investments in sustaining knowledge creation. By institutionalising precarity, this move will not only devalue academic labour but also jeopardise its role as a reliable custodian of critical thought and innovation.

This institutionalising of academic precarity will also be used to attenuate resistance of teachers first (by furthering pro-establishment union leaders in the short run) as a prelude to the elimination of all resistance by teachers that seek to defend public higher education. Academic precarity is, after all, a central (but ‘de facto’) plank of the National Education Policy 2020.

The provision for compulsory retirement is also a tool to implicitly cast aspersions on the cohort of teachers who were appointed prior to the current ruling dispensation. In this way, the provision for compulsory retirement for senior teachers is also calculated to drive a wedge in the relations of solidarity that permeate comradely networks between senior and junior faculty (and between teaching and non-teaching employees), especially their unions.

Likewise, periodic performance review is also a means to divide teachers by signalling to them that they are seemingly secure if they do not organise themselves for upholding their rights. But past experience indicates that these unions are often more resilient than is given credit for by neoliberal practitioners of policies of divide and rule. The recent victory of the Samsung India Workers Union (in Tamil Nadu) is an example of how the neoliberal project can be pushed back by determined resistance.

Besides, the potential for misuse of compulsory retirement provisions further compounds its adverse impact on education. Without robust safeguards, such measures could enable arbitrary dismissals, patronage-based retention, or the silencing of critical voices. Let us assume for the sake of argument that in government, checks and balances exist to mitigate such risks. But in academic settings, where governance structures are distinct, similar protections are often increasingly absent. The absence of transparent criteria for evaluating "ineffectiveness" or "doubtful integrity", especially in academic roles, leaves room for subjective misinterpretations, potentially enabling administrative overreach that will have a debilitating impact on education. This ambiguity contravenes principles of natural justice and due process, which are vital to maintaining trust within academic communities.

Compulsory Retirement, Periodic Review Are Irrational

The rationale behind compulsory retirement and periodic performance review in government services—to eliminate inefficiency and corruption—is not only ill-suited to academic contexts; it is also inconsistent with authentic democracy and, therefore, irrational in public life.

Conventional notions of government see it as an instrument of service delivery. However, authentic democracy involves a participative reorganisation of public activities. The determination of what is authentic in public activities is not technocratically given. But when it is falsely assumed to be given, then short-termist microeconomic cost minimisation of such service delivery emerges as a means to eliminate "deadwood". Whether a public servant is necessary for public service cannot be a context-independent determination. Public intervention rather than public service captures this crucial difference. Public intervention is by definition context-specific. Moreover, quite often the process through which the public intervention transpires is itself both a cause and an objective of the public intervention.

For instance, a change in the social composition of teachers and students toward one which is reflective of the country as a whole will not only enhance the representation of those who were marginalised till now but will also increase the efficacy of education through the incorporation of greater diversity. Under these circumstances, where the government has multiple objectives, traditional short-termist microeconomic cost minimisation through eliminating "deadwood" would become irrational.

The challenge for Indian democracy is to combat neoliberal irrationality by drawing on the basic structure of the Constitution to develop a participative work ethic that derives from tenure and is, therefore, not coercive. Public intervention rather than service delivery is the democratic terrain within which this challenge can be purposefully encountered.

Moreover, the short-termist microeconomic rationale implicit in targeting senior faculty—higher salaries and pension liabilities—reveals a misguided prioritisation of the aforementioned irrational considerations over sustainable quality of education. While this holds evident appeal to neoliberal policymakers, it overlooks the long-term social repercussions of destabilising academic institutions.

Experienced faculty drive research, international collaborations, and facilitate interdisciplinary dialogue that spans both the academic domain and beyond, all of which contribute to enhance the quality of education internationally. Replacing them with lower-wage contractual staff may seemingly yield short-term savings, but it risks diminishing the university's reputation and capacity for innovation. This approach mirrors broader neoliberal trends in education, where short-termist microeconomic manoeuvres displace pedagogical and scholarly priorities conducive to long-term development.

This type of cost saving is also macroeconomically irrational. The salaries of senior teachers, like senior workers in all fields, constitute a stable and rising source of macroeconomic demand that can support enterprises during different phases of business cycles, especially during downturns. In fact, when enterprises are aware that such a stable source of macroeconomic demand exists, then their investment itself will become less volatile in response to fluctuations in such demand. In turn, this attenuation of volatility in investment will contribute to the stabilisation of macroeconomic demand. This stabilisation of demand, needless to say, provides an environment that is relatively more conducive to the introduction and diffusion of innovation in the economy. It is, therefore, quite likely that the short-termist microeconomic proclivity to cut costs by dispensing with senior workers, including senior teachers, will lead to a pile-up of macroeconomic costs that could be orders of magnitude larger, resulting in the emergence of macroeconomic irrationality.

However, the persistence with this irrational trajectory is reflective of a larger design to privatise and commercialise all domains of public life, including higher education.

Conclusion

The consideraion of the extension of the Union government’s circular on compulsory retirement of government employees and periodic performance review to university teachers is a prelude to the de facto extension of CCS rules to the teachers of Delhi University. It represents a profound misstep, both legally and democratically. It disregards the statutory autonomy of universities, undermines academic freedom, and misapplies an irrational neoliberal tool to an environment where intellectual independence is paramount. After all, the ethos of a socially purposeful higher education thrives on the dialectic between tenure and critical inquiry, which alone results in long-term socially relevant scholarly contributions. By prioritising short-termist microeconomic considerations and conformity over academic excellence and macroeconomic rationality, this neoliberal policy risks eroding the university's role as a beacon of knowledge and innovation in the development of the country. Therefore, the committee set up to consider the extension of CCS based periodic performance review (which will enable compulsory retirement) must unconditionally reject this extension.

To preserve the integrity of higher education, it is imperative to collectively resist this neoliberal project to privatise and commercialise higher education through the furthering of academic precarity. This resistance has the potential to propel the University of Delhi to draw on its own Act, Statutes and Ordinances (within the framework of UGC Regulations) and the expertise of its academic community, including students, teachers and non-teaching staff, to develop democratic governance mechanisms that reflect the unique demands of scholarly endeavours to further innovation. Only by doing so can it uphold its democratic mandate to foster a vibrant, critical, diverse and inclusive intellectual culture.

Mithuraaj Dhusiya is Associate Professor, Department of English, Hansraj College, University of Delhi, C Saratchand is Professor, Department of Economics, Satyawati College, University of Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.