The Amauta Mariátegui and the Commander Che

Two crucial Latin American Marxist thinkers and revolutionaries: Ernesto Che Guevara (left) and José Carlos Mariátegui (right)

June 14 marks the birth of two of the most important revolutionaries and Marxist thinkers in Latin America: José Carlos Mariátegui La Chira (1894-1930) and Ernesto Che Guevara (1928-1967). The Peruvian forefather of Indo-American Socialism and the Argentine internationalist of the Cuban Revolution may have not known each other personally, but they had a special relationship, proving themselves necessary and essential to each other.

The relationship between Mariátegui and Che Guevara is an ongoing one. It is thanks to Mariátegui’s work we remember, in the way that we do, the revolutionary Che Guevara. And thanks to Guevara we can have more access to Mariategui’s legacy. This idea is based on a story told by Argentine revolutionary comrade Vasco Orzacoa, one of the fighters of the historic Cordobazo, during a meeting held to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Che Guevara’s assassination in La Higuera, Bolivia by US Imperialist agents.[1]

How did Mariategui influence Che Guevara? Orzacoa said that he met Che Guevara’s sister in Spain when he was in exile. Comrade Vasco told her he lived in the same Street where Guevara La Serna family home was located, when the family moved from Rosario to Córdoba searching for better weather for little Ernesto Guevara’s asthma. Then, she asked him if he knew that the house next to the Guevara family house was Gustavo Roca’s. Gustavo Roca was the son of lawyer Deodoro Roca, one of the leaders of the University Reform movement, which began in Córdoba, and author of the Manifiesto Liminar which was a fundamental guiding text for the landmark movement.

During the period of the dictatorship, most of the books in Deodoro Roca’s library were safeguarded in this house. According to Che’s sister, it is precisely in that library where the teenager Ernesto snuck into to unleash his infinite capacity as an inveterate reader. He skipped school to immerse himself into José Ingenieros and Aníbal Ponce books, among others. This fact was confirmed by Orzacoa reading letters written by the teenager Ernesto Guevara to a young female comrade of the Argentine Communist Party.

Vasco Orzacoa highlights an important similarity between Ernesto Guevara and Roca, both consciously chose to educate themselves from our continent instead of following a eurocentric and colonial path. It is important to note that, in the beginning of the 20th century, the path of privileged young people was to travel to Paris and other European cities. But Ernesto Guevara was different. He got on a motorcycle, named “La Poderosa” (“The Powerful”), along with his accomplice in the adventure, Alberto Granado, and embarked on a trip to see all the diversity and richness of America. Today, we can say that the route they traveled could be understood as a Qhapaq Ñan (the Incan road system) route for revolutionaries.

As Che himself describes in his travel diary “Motorcycle Diaries”, later made into a film, Ernesto and Alberto arrived in Peru with limited resources to advance their bizarre journey and in this context they are received by the Peruvian Doctor Hugo Pesce. The Marxist Doctor Pesce provided them with shelter, food, and financial support. Pesce also took the two young doctors, Guevara and Granado, to a hospital with leprosy patients in Lima so they could volunteer their medical knowledge to treat patients. The message of solidarity and internationalism is clear in this episode.

This was also the moment where Hugo Pesce introduced José Carlos Mariátegui to Ernesto Che Guevara. Pesce was a revolutionary friend, comrade, and disciple of Mariátegui. He was one of the Peruvian representatives, appointed by Mariátegui, in the Trade Union Conference of Montevideo and the First Communist Conference in Buenos Aires, which both took place in 1929.

As Alberto Flores Galindo says in his book “La Agonía de Mariátegui” (“The Agony of Mariátegui”), in such meetings, the original and authentic thinking developed by Mariátegui confronts and engages in debate with the European mainstream orthodox Marxist approach. Hugo Pesce was a sort of messenger of the thought accumulated by José Carlos Mariátegui.

According to the correspondence between Che and his mother, during his visit in Lima he had long conversations with Hugo Pesce in his house. Guevara says these dialogues started at night and went until dawn. Vasco Orzacoa asked himself, what were young Ernesto Che Guevara and Mariátegui’s Comrade Hugo Pesce talking about so much? He believed, and we agree, that it was likely about Mariátegui’s thinking, for in those days of military dictatorship in Peru, even writing about the Communist Party which Pesce belonged to, was forbidden. So, the Amauta of Indo-American Socialism was present in the process of political development of the Argentine revolutionary internationalist. Later on, Mariátegui’s footprint can be identified in different works by Commander Che Guevara.

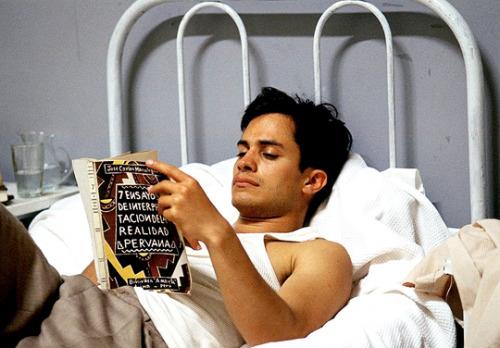

In the 2004 film ‘Motorcycle Diaries’, Che is depicted reading Mariátegui’s landmark book ‘Seven Essays’

How did Che Guevara revive Mariátegui? Comrade Vasco Orzacoa said that when he lived in Peru in the 80s, he found an old Mariátegui book at a book fair. When he opened the book and started to read, on the first page he discovered that it was published by the Ministry of Industry of the Cuban Revolution. And, who was the Cuban Minister of Industry during the year that text was published? Our Commander Che Guevara.

In other words, the first massive publication of the emblematic work of the father of Indo-American socialism took place in revolutionary Cuba and from the ministry under the control of Che. The Cuban Amauta Fernando Martínez Heredia confirmed this when he said that the generation prior to the 1959 Revolution was already aware of Mariátegui’s ideas and that Cuba was the first socialist country to undertake the publication of the Seven Essays. He also emphasized the demonization of the reflections of the Peruvian not only by the ruling class but also by the “orthodox” communism of the moment:

“By the way, when you study the Cuban Revolution more, you will see how a generation prior to the triumph of the Revolution began to be influenced by Mariátegui, such as President Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado, who at the age of 17 published a short article…about Mariátegui, when he was considered the devil. They assumed that it was a deviation from Marxism, and the Peruvian Communist Party was congratulated by the Communist International in 1934 for waging the fight against ‘the Mariateguist deviation’ at the center of its ideological struggle. And in 1937, 1938, the young Dorticós wrote a short article very much in favor of Mariátegui. Later, especially in the first years after the triumph of the revolution, Mariátegui had tremendous importance here and [Cuba] was the first socialist country in which ‘Seven Interpretive Essays on Peruvian Reality’ was published, this was done partially at the end of 1959 and totally in 1961.”

Returning to Orzacoa’s testimony, he recounted that there was correspondence between Che and Dr. Hugo Pesce, already after the triumph of the revolution, wherein Che asks the doctor to go to Cuba and to not forget to bring the manuscript of the ‘Seven Essays’. This is how Che revives the valuable contribution of the Father of Indo-American Socialism.

Why do we say revives him? Let us not forget that Mariátegui and his thesis of Indo-American socialism that put the spotlight on the Indigenous as a revolutionary subject and challenged the current of European orthodox communism and its satellites in our continent, was banned (even demonized, in the words of Martínez Heredia) from the Peruvian, Latin American and world communist environment. In times when there was no wordpress, no alternative digital media and the communist parties monopolized the printers and publishers that could publish this quality of work, this meant that Mariátegui’s legacy was forgotten, except in the files of Dr. Pesce. Let us not forget the event recounted by Flores Galindo in “The Agony of Mariátegui” when Hugo Pesce, during the First International Communist Conference in Buenos Aires in 1929, gave a copy of the ‘Seven Essays’ to Codovilla – an Italian communist representative of the Communist International in Latin America – to ease out some tensions held in the debate with the Peruvian delegation. Codovilla’s response minimized and undervalued the revolutionary contribution of Mariátegui:

“Perhaps with a certain desire for conciliation and to break the marginalization that began to arise in the conference, in one of the interruptions of the meeting, Pesce approached Codovilla to give him something that was a source of pride and affirmation of the Peruvian delegates: a copy of the ‘Seven Interpretive Essays on Peruvian Reality’. Codovilla, who at that time also by chance had Ricardo Martínez de la Torre’s pamphlet on the labor movement in 1919, looking at Pesce and with the intention of being heard by the other delegates, said in his usual emphatic tone that the work of Mariátegui had very little value and, on the contrary, the example to follow as the Marxist book on Peru, was that pamphlet by Martínez de la Torre. This anecdote was reported by Pesce and endorsed by Julio Portocarrero.”

For all this, and surely more, the coincidence of the birth of both revolutionaries on June 14, each with their own processes, their marked periods of political development in their youth (Juan Croniquer – Mariátegui’s pseudonym in his journalistic youth – and the adventurer Ernesto Guevara on his Poderosa), their contradictions, and above all, their lucidity and love for Our America, is not just a date but it marks a reciprocal relationship between comrades in struggle. Each one revived the other, without imitation or copying, but as heroic creation.

José Carlos Llerena Robles is a popular educator, member of the Peruvian organization La Junta.

[1] https://lepondregatilloalaluna.blogspot.com/2017/10/homenaje-al-che-guevara-el-legado.html

[2] https://medium.com/la-tiza/c%C3%B3mo-investigar-la-revoluci%C3%B3n-cubana-i-2d5a9c18ce7a

[3] https://www.marxists.org/espanol/floresgalindo/1980/desco00006.pdf

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.