Welcome U-Turn, Mr PM, but India’s Vaccine Woes are Far from Over

While the partial withdrawal of the government’s disastrous “liberalised vaccination strategy” is welcome, India’s vaccine woes are far from over. The country’s vaccination programme so far is marked by inequity, inefficiency, and opacity. This must change if the country’s vaccination programme is to be effective.

The “liberalised vaccine strategy”, as it was called by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in its press release, was in place for the month of May and had come under severe criticism for its inequity and inefficiency from state governments, Opposition parties, civil society, and even the Supreme Court.

In its partial withdrawal of this strategy, the Central government has at least course corrected to some extent. However, it has still reserved 25% of the total doses produced in the country for the private sector, i.e., for the urban rich. The government must withdraw this too, and revert to a strategy of universal free vaccination.

Till the May 31, 2021, only 12% of India’s population was partially vaccinated (given at least one dose), and only 3% was fully vaccinated (given both doses). The Prime Minister in his speech criticised some critics of the government for questioning the strategy of prioritising by age group. He chose to ignore, however, that most sensible critics had not opposed the age-wise prioritisation but had taken issue with this being the only criteria for prioritisation, beyond health care workers and a loosely defined category of frontline workers. Many had asked that other categories of essential workers, and those forced to live in conditions where physical distancing is not possible, be included in the government’s priority categories.

However, even if we consider only the government’s own age criteria for determining vulnerability, we see that less than half (43%) of those above the age of 60 have got even partially vaccinated. Fully vaccinated persons in this category are far less. So, the government has fallen far short of meeting even its own targets, almost 4 months into its vaccination programme.

Of those between the age of 45 and 60, only 25% have got at least one dose. The age cohort that was made eligible for vaccines only in May and asked to pay for their shots, has been the most poorly covered so far with only 4% at least partially vaccinated.

As health experts had warned right at the start, it is becoming increasingly clear that depending on self-registration on the CoWin portal alone cannot ensure effective coverage. Notwithstanding his praise of the portal in his speech, the Prime Minister must recognise that this strategy of registration is highly inequitable in a country where a large majority of the population lacks access to the internet and cannot read, speak, or write in English, the only language available for use on the CoWin portal.

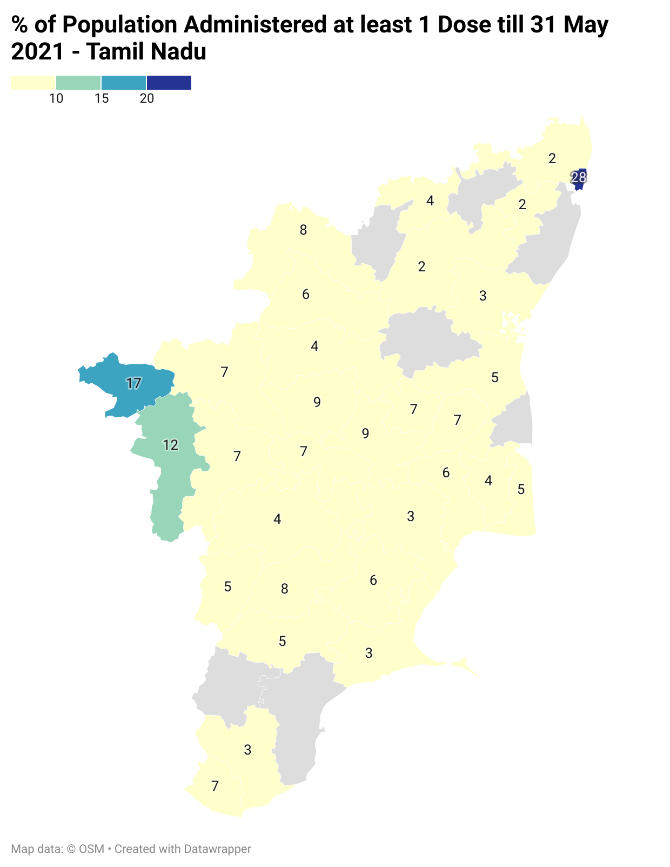

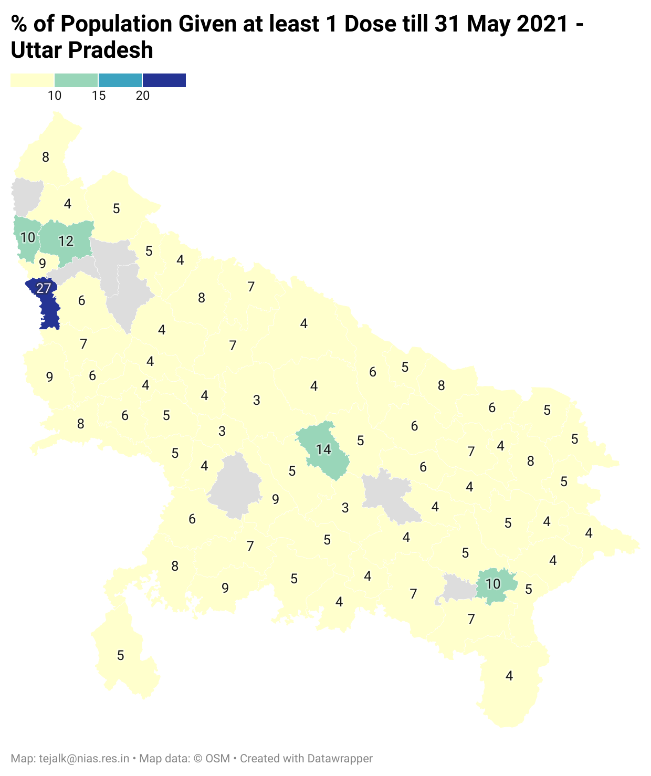

The disparity in vaccine distribution is visible across states and also within states. Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Assam, and Tamil Nadu have covered less than 10% of their eligible populations so far. While the Prime Minister has said that allocations to states will be declared a week in advance, the criteria used so far, and will be used in the future for vaccine allocation, is still not clear.

One press release in April from the MoHFW had said that allocation would depend on case load and performance in vaccine administration, while another statement said, it will be population based. The government must declare just and objective criteria for vaccine allocation to states, arrived at via consultation with health sector experts and state governments, in a transparent manner.

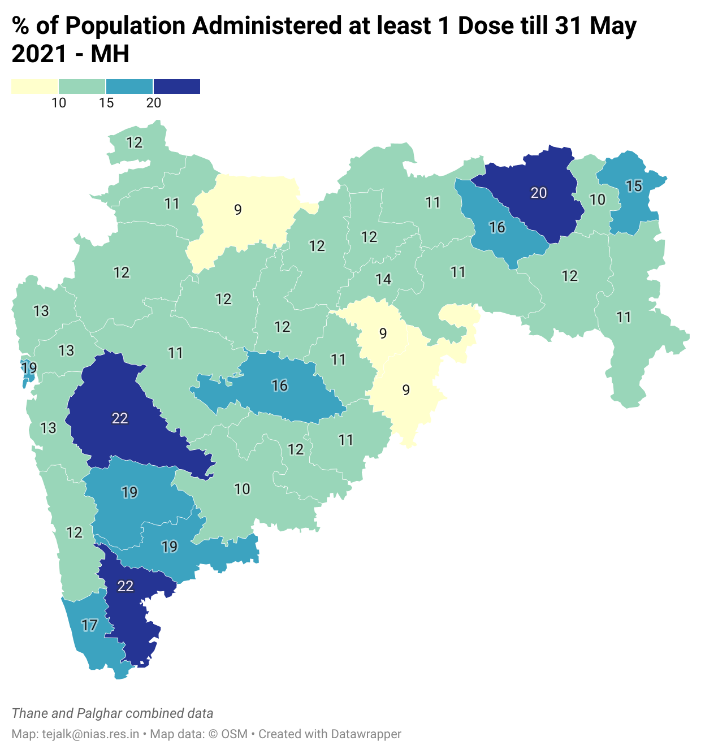

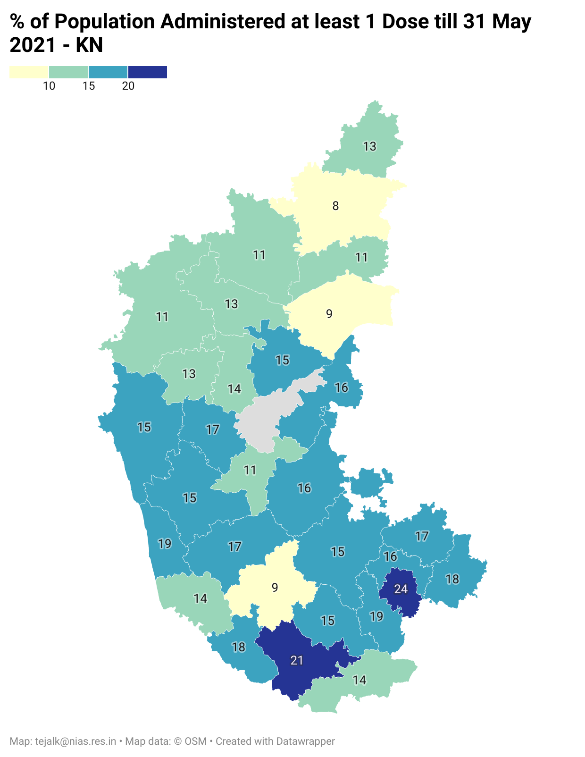

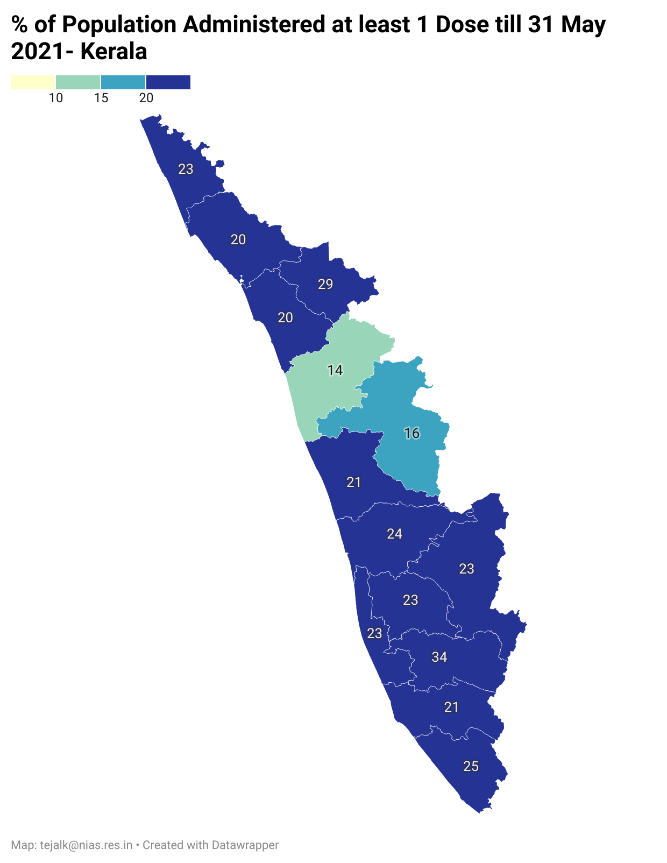

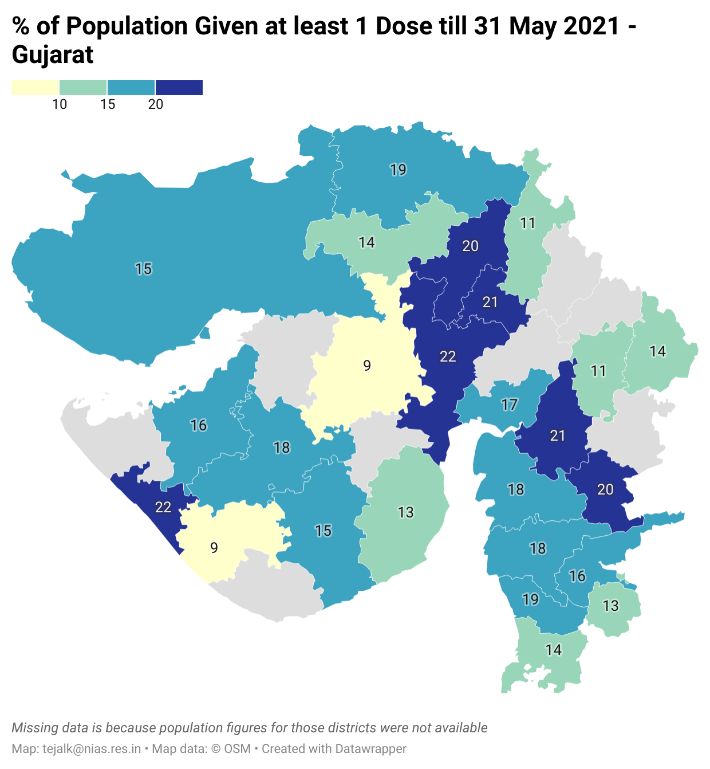

On their part, state governments must also ensure that vaccine distribution within their respective states is equitable. Currently, most of the vaccination drives are concentrated in urban areas. An analysis of six states is shown here – Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh.

In Maharashtra, the coverage in Pune, Nagpur, Kolhapur, and Mumbai is much better than in the other districts (See Fig: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/XdxUz/2/ )1. The distribution is similar in Karnataka, with just Bengaluru and Mysuru with a higher than 20% coverage (See Fig: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/ilzRJ/2/ )2

Kerala has much more equitable vaccine coverage across districts, almost all of them with above 20% coverage (See Fig:

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/bWQ3u/2/ )1.

Tamil Nadu is at the opposite end, with highly unequal vaccine coverage. Most districts in Tamil Nadu have less than 10% coverage. Only Chennai has a higher than 20% coverage (See Fig: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/iyERU/2/ )1.

Gujarat (See Fig: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/Ai07n/2/ )1 and Uttar Pradesh also illustrate the skewed distribution of vaccines across urban and rural districts within the states. In Gujarat, the Gandhinagar corporation region has covered about 55% of its population with at least one dose. But the rest of the district has only 16% coverage. Similarly, Jamnagar corporation region shows coverage of about 33%. But coverage in the rest of the district is only 10%. In Uttar Pradesh, other than NOIDA (Gautam Buddha Nagar), in no other

district has more than 20% of the population been covered (See Fig: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/7gpPU/1/ )1.

Central government spokespersons have repeatedly sought to assure people that India will be able to vaccinate its entire eligible population by the end of this year. However, to do this, the monthly vaccination rate must increase four-fold. Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh will have to increase their monthly vaccination rate by seven times, Bihar and Jharkhand by six times, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Punjab by five times.

Even to partially cover the entire population (i.e. administer at least one dose to the entire eligible adult population), Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand will have to increase vaccination rates five fold as compared to their current rates.

A major obstacle to such multifold increase in vaccination rates remains the severe shortage of supply. The government has allowed some public sector units to finally manufacture Covaxin. However, the delay in taking this route has meant that vaccine supplies from these units will not be available in the near future, i.e. will take at least 6-8 months more.

On the other side, there is still no clarity on the existing capacity of vaccine production and the actual supply of doses per month. A press release in May by the MoHFW shows projections for vaccine production from different sources for the rest of the year (See Table). The projected increase in production is extremely high and the government continues to be extremely untransparent on the basis of these projections, and the assumptions and data used to arrive at the same.

According to all reasonable indications, vaccine shortages will last for a few more months at least. In this situation, the strategy of keeping 25% of the doses reserved for private hospitals and centres will further exacerbate the vaccine inequality that we already see across the country.

Media reports have shown that almost 50% of the vaccines available to the private sector in May, were procured by only nine major corporate hospitals, and the even the remaining 50% by only 300 odd hospitals, most of whom did not serve the population beyond Tier-2 cities. Why do the urban rich, who in fact can more easily practice physical distancing, very often have the option of working from home, and have easier access to healthcare infrastructure, get to call dibs on a significant share of the country’s preciously scarce vaccines?

Going forward, the government must make all efforts to increase vaccine production and it must procure 100% of the vaccines and distribute them to states, free of cost, based on just and objective criteria, transparently communicated to the public.

States must also plan their vaccine administration strategies to ensure equitable coverage across regions and economic classes.

An acknowledgement of the unvarnished truth about vaccine shortage and strategies to maximise effectiveness given this situation, is the only way to reduce risks of future outbreaks. We have already seen the results of hubris in the devastating second wave that the country had to face. Let us avoid making the same mistake on vaccinations.

Table. Data from MoHFW Press Release in May 2021 in Vaccine Availability in Year 2021

Source: MoHFW press release, May 2021

The writer is an associate professor at National Institute of Advance Studies, Bengaluru. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.