Rising Elephant Menace More than Animal- Human Conflict for Adivasis of Chhattisgarh

Displaced, dislocated and hungry, elephants search for food and forest cover inside a village.

Courtesy: Rajesh Tripathi, Jan Chetna Manch, Raigarh, 2020.

Seemingly, the Animal–Human Conflict (AHC) is at the heart of the destruction trail unleashed upon local communities by the moving and migrating herds of wild elephants in the forests of Chhattisgarh.

Conflictual claims on dwindling natural territory and space are re-defining the ways in which humans and animals associate with each other. Even for routes that are regular elephant corridors, such as the Jashpur and Sarguja, where the tribal and other forest dwellers have acquired an expertise in tackling the menace, tragedies are no longer ruled out.

However, there are other areas, such as in Bhanupratapur in Uttar Bastar Kanker district of Chhattisgarh which have not been a traditional elephant route. Here, the repeated incidents of destruction due to sudden elephant rampage are being seen as rising AHC.

Given that all known philosophies and practices of tribal and forest dwelling communities centre around living harmoniously with nature, this articles argues that the notion of human ‘conflict’ with other species and vice-versa needs to be unpacked with a more cautious understanding of the ‘local’, especially vis-à-vis the administrative realities of crisis management.

To bring the adivasi perspective on the AHC into the picture, Adivasi Jan Van Adhikar Manch (AJVAM), a civil society platform working for tribal rights in Chhattisgarh, invited our team of volunteers to the elephant menace affected areas.

Along with members of the Jan Chetna Manch, we travelled through Uttar Bastar Kanker and Raigarh (in Chhattisgarh) during November 2021, to interact with the tribal communities.

‘Angry, hungry, wild and destructive’ is how the residents of Daabkatta and Mardel villages in Uttar Bastar Kanker described the herd that stormed through their food, fodder, houses and farms during the peak of the second spike of COVID-19 in India.

We found that the affected families were disgruntled by the way in which the government delivered as well as distributed compensation packages despite the raging pandemic and the advocacy that picked up around the issue in the summer of 2021.

Non-Transparent Political Economy of Compensation

Daabkatta, is a village that comprises 50-60 families. One of the residents showed us the ruins of her house of which virtually nothing was left once the elephants destroyed it in May 2021. The wild elephants not only brought down the walls, façade and ceiling of the house but also destroyed her belongings. Her family incurred an approximate loss of Rs 200,000. Provided a mere Rs75,000 as compensation, she is now determined to fight for the rightful amount.

After the elephant attack in May 2021in Daabkatta, Bhanupratapur, her house, exclaims the owner clad in a saree in the picture above, virtually disappeared from the scene. Almost nothing was left of it.

Photo: Bobby Luthra Sinha, November 2021.

In Mardel, we met N. P. Uike, a middle- aged woman, who lost her house to the elephant menace. Due to the rainy season that followed close on the heels of the destruction and the seasonal exigencies of farming thereafter, Uike has been unable to rebuild her house.

K. Bai of Daabkatta Village, Bhanupratapur stands i where her mud-house once stood and is determined to claim her rightful compensation so that she can re-build her property.

Photo: Bobby Luthra Sinha, November 2021

In Mardel, we met N. P. Uike, a middle- aged woman, who lost her house to the elephant menace. Due to the rainy season that followed close on the heels of the destruction and the seasonal exigencies of farming thereafter, Uike has been unable to rebuild her house.

During the unexpected elephant raid on the village on May 17- 21, 2021, the Mardel residents were so scared that they would cook early in the morning and hide in their fields far away from their homes.

An example of what a mud-house looks like once the pachyderms have done their job. Mardel, Bhanupratapur.

Photo: Bobby Luthra Sinha, November 2021.

Pushpa Soren, part of the AJVAM team on ground, received many frantic phone calls for help from the neighbouring villages of Daabkatta, Peecheykatta, Cheench gaon, Ira gaon during the height of the crisis. Soren reached out to the villagers but faced stiff resistance from the sarpanch (village headman) of one of the villages who taunted the villagers for asking the civil society to step in.

P. Kangi, a young man from Mardel confirms that, “while the sarpanch failed to even visit us or use the emergency fund at his disposal to help us out, he berated social workers who tried to distribute us food and other sundry essentials.”

Ruins of Uike’s house in Mardel Village, Bhanupratapur, Uttar Bastar Kankerr.

Photo: Bobby Luthra Sinha, November 2021.

For expediting governmental response on the issue, the AJVAM convener advocated the cause with the alternative media in Bastar. This was complemented by the efforts of a social scientist from Delhi who volunteered to acquaint the forest department officials with evidence-based information of destruction coming in from the ground. Thereafter, as the news was picked up by the media, the forest administration announced and disbursed Rs 1.54 crore to help the locals.

It was agreed between the government and people that two surveys would be carried out to collect evidence on claims and decide the compensation. While the survey by AJVAM reported around 100 families in Mardel and nearby villages with varying losses, government representatives enumerated 153 families for the same region.

“When compensation arrived”, says Soren, “some got little or no compensation despite huge losses while others who incurred lesser damages received larger amounts”. In addition, it never became clear who the extra 53 families in the list were and why they received compensation from the government?

Even the main structure of the cowshed outside Uike's family home in Mardel village was destroyed and its wooden boundaries were damaged.

Photo: Bobby Luthra Sinha, November, 2021.

H.L. Kange from Mardel said, “None of us could fathom the criterion of aid distribution. Besides, second-hand and low- quality material was delivered to families in need”. S. L. Kange from the same village lamented that he got only Rs 4,000 as compensation. He still wonders how the government arrived at that figure.

While compensation packages are not sufficient in many cases, they are also late and arrive after momentous efforts and activism. While the people wait for advocacy to alleviate their situation, they remain anxious and isolated.

Left to their own devices in the ace of dwindling forest cover and resources, and especially in zones that are new to facing the ire of the wild elephants, the tribal people may be forced to resort to spontaneous, home-grown self-defence strategies. These include scaring the animals away by hook or by crook.

Often described as the manifestation as well as the cause of a bourgeoning AHC, these local strategies of self-defence may or may not be successful. Amateur remedies carry the danger of landing forest dwellers in grave problems, as in reality these are desperate attempts at solution-seeking by trial and error methods.

The buck must stop somewhere

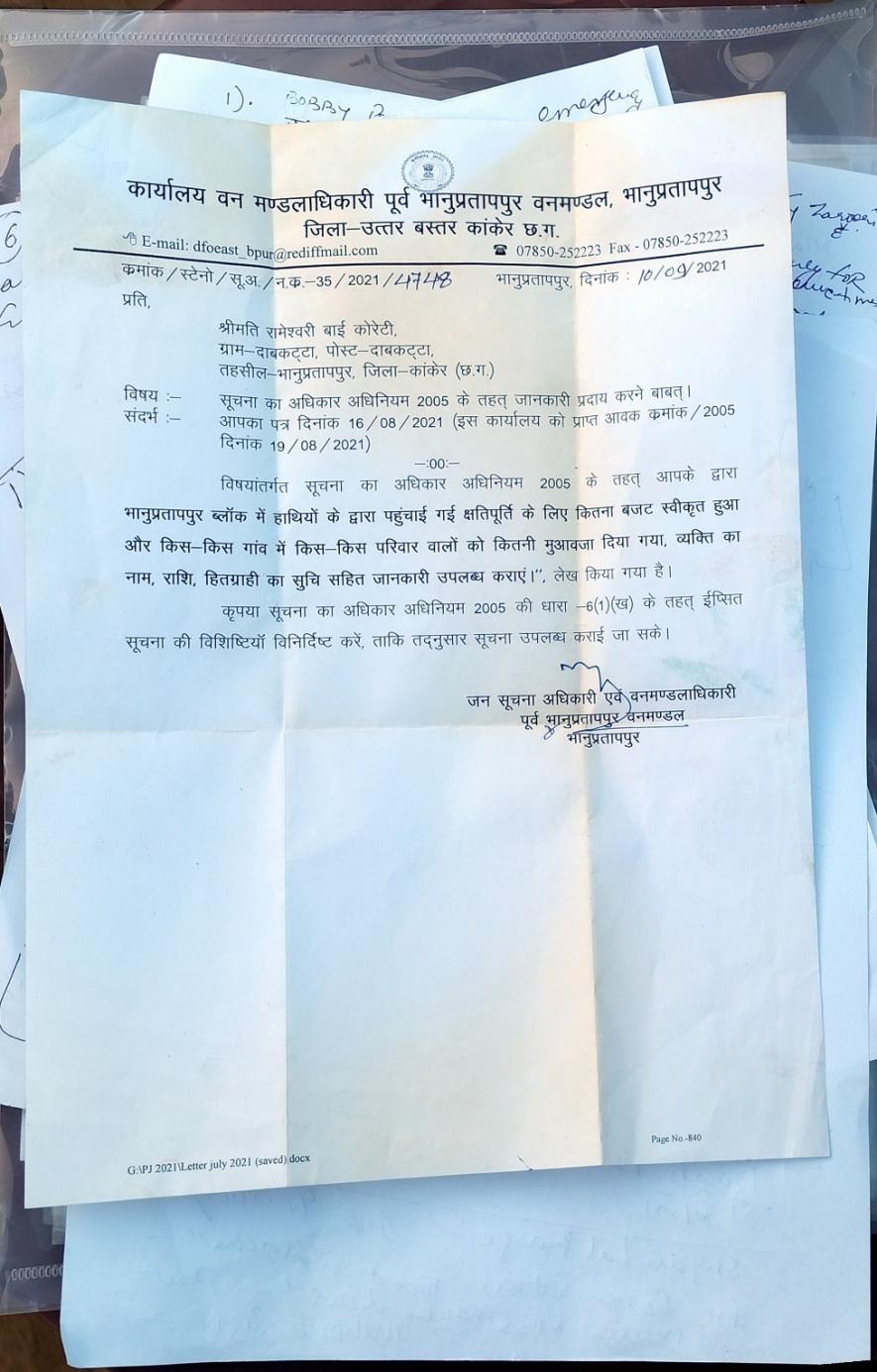

In search of answers, a woman named SB Koreti moved an RTI query against the forest department in Bhanupratapur demanding that compensation be delivered impartially.

Photo: Bobby Luthra Sinha, Mardel Village, November 2021.

Rajesh Tripathi, a known environment rights activist from Jan Chetna Manch in Raigarh said that “even in tribal areas which have been traditional elephant corridors, what is not so normal any longer is the frequent and increasing visits by elephant herds. Desperate in search of food, and displaced owing to increasing mining activities in Raigarh as well as Sundargarh and Jharsuguda, the bordering areas of Chhattisgarh with Odisha, elephants have begun to attack fields as well as homes indiscriminately.”

Between 2013 and 2021, in Gharghoda, Dharamjaigarh, Sarangarh, Lailunga, Kharsiya and Tamnar Blocks of Raigarh, 5,493 cases of loss of property and crop damages were registered. In Dharamjaigarh, 126 people died due to the elephant menace during this period.

Sajal Madhu, founder of ‘Haathi Mera Sathi’ points to an advancing herd seen suddenly in Dharamjaigarh in Raigarh, Chhattisgarh.

Photo: Rajesh Tripathi, Jan Chetna Manch, Raigarh, 2021.

A total of 26 elephants died between 2017 and 2021 owing to electrocution caused by low-lying electrical poles in Raigarh, said Tripathi. Along with Sajal Madhu, founder of an organisation called, ‘Haathi Mera Satthi’ in Raigarh, Tripathi has been advocating the safety of animal and human life. Alas, matters move slowly in Chhattisgarh!

Animal-Human Conflict or Animal-Administration Conflict?

Savita Rath from Jan Chetna Manch said, “The government leads awareness campaigns in the elephant-affected villages and zones, even distributes remedial literature on self-defence during pachyderm attacks. It also stealthily facilitates environmental clearances to miners by declaring that these very villages and zones are bereft of animal presence and can be used for industrial purposes.”

Two things are clear:

a) No community or individual deserves to live in perpetual fear and/or uncertainty, and wildlife too needs protection;

b) Both issues are not separate from each other. Much of the inertia and impasse would ease if the government of Chhattisgarh:

From 2005 to 2021, Dharamjaigarh has seen the deaths of 126 tribal and other forest dwellers owing to elephant menace whereas a total of 50 elephants have also died in the same period.

Photo: Rajesh Tripathi, Jan Chetna Manch, Raigarh, 2021

-

Mandates strict compliance with environmental laws, closure guidelines and restoration of natural resources by mining companies;

-

Implements the Forest Rights Act (2006) and habitat rights therein, of the adivasis and other local communities in the full spirit of national and international law;

-

Expedites the distribution of aid and compensation packages transparently.

Need for humanitarian visions and practices in India

For all practical purposes, the tribal communities suffered a double pandemic but utilised their collective and individual survival skills. Amidst lack of health care and outreach, the adivasis also lived out additional problems such as administrative seclusion in face of rising elephant menace.

The struggles faced by vulnerable adivasis and other forest dwellers to survive through natural as well as man-made crisis indicate that it is time we re-imagine the way we accept, analyse and manage several environmental anomalies and problems. Civil society organisations and networks have made considerable strides in order to reach out, learn from, as well as guide the tribal communities in Chhattisgarh through the COVID crisis. It is now the turn of the state to set for itself newer frontiers of thinking and preparedness to ensure the well-being of the adivasis as well as natural resources in the country, with or without the pandemic.

Dr Bobby Luthra Sinha is Co-Chair of Migration Commission at International Union for Anthropological and Ethnographic Sciences and Deputy Director of the Centre for Asian, African and Latin American Studies at the Institute of Social Studies, Delhi

Indu Netam, an activist and tribal leader, is Convenor of the Adivasi Jan Van Adhikar Manch, which works to secure the environmental, cultural and constitutional rights of tribal communities.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.