NIRF 2021 and the Invisibilisation of Exclusion in Indian Higher Education

Image Courtesy: NewsBust India

The “India Rankings 2021” instituted by the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) was released by the Union Ministry of Education (MoE) on September 9, 2021. Launched in 2016, the 2021 rankings are the 6th consecutive edition of the Framework’s score-based ordering of Indian Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). 4030 such individual HEIs applied to be considered under the 2021 rankings, marking an increase from 2426 that did so under the inaugural list.

The release of the 2021 rankings has generated considerable discussion in its wake, with a number of individuals and institutions hailing those that have come out on top of the 11 categories into which HEIs were divided. Multiple narratives have problematised the very concept of ranking HEIs, linking the same to the neoliberal commodification of education. It is important, however, to also note in addition to the above how under the guise of merit, the NIRF ranking attempts to obfuscate the continued denial of access to education that certain sections of India’s citizenry are faced with.

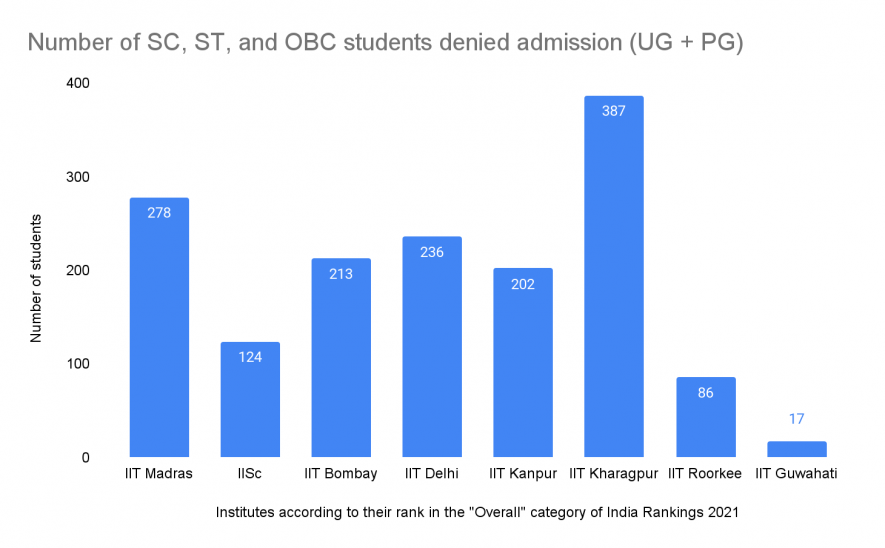

The above may be illustrated by considering the “Overall” category under the 2021 rankings. The list is dominated by some of India’s Centrally Funded Technical Institutions (CFTIs), with 8 of the top 10 ranks going to the IITs and the IISc. JNU and BHU - both Central Universities, rank 9 and 10 on the list respectively. Considering data made available as a part of the rankings, it is evident how students from SC, ST, and OBC communities have been denied a place in the above institutions, with reservation provisions being subverted to convert reserved seats into unreserved ones.

In absolute numbers, the situation seems to be the most alarming at IIT Kharagpur, where 387 seats meant for SC, ST, and OBC students have instead been occupied by “General” category students. At IIT Madras, where just in July 2021 an Assistant Professor was forced to resign owing to the rampant practice of casteism in the Institute, 278 SC, ST, and OBC students have been denied a place. The situation is similarly egregious across the other CFTIs in the top-10 list of the “Overall” category. Cumulatively, 1543 students from SC, ST, and OBC communities have been denied a place to study at the UG and PG levels in just these institutes, as per the data made public by the NIRF.

Source: India Rankings 2021, Author’s calculation

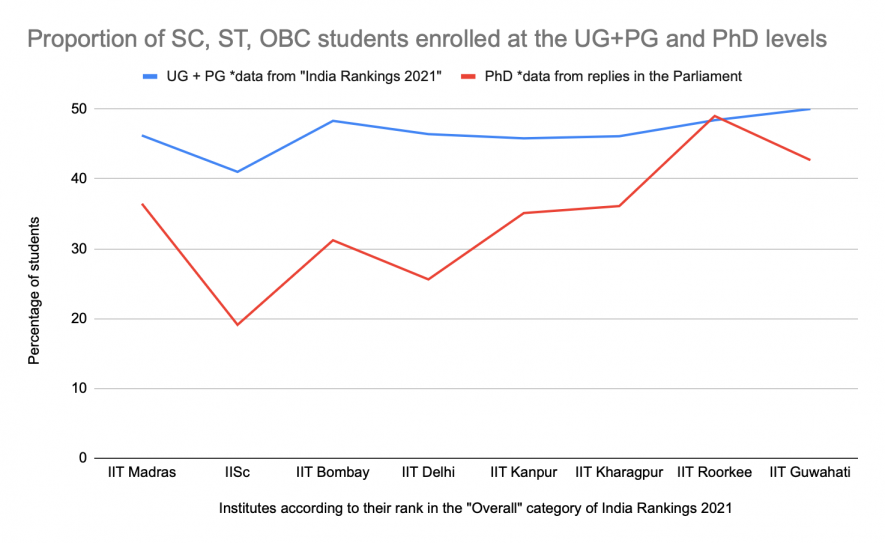

Needless to say, however, this figure dramatically understates the actual number of marginalised students who are denied a place in these HEIs by design, since the above numbers pertain strictly to enrollments only at the UG and PG levels and do not consider the enrollment of students in PhD programmes. While at the UG and PG levels 46.2% of all students come from marginalised communities at IIT Madras, this figure falls to only 36.4% for PhD programmes at the Institute, according to data presented before the Parliament. The situation is particularly distressing at IIT Delhi, where only 25.6% of all PhD students hail from SC, ST, and OBC households. At the IISc, this figure falls further to 19.1%, with only 401 students from marginalised caste households being granted a place at the Institute’s PhD and Integrated PhD programmes between 2016 and 2020.

A submission made by the erstwhile Ministry of Human Resource Development before the Parliament on 12th March 2020 went on to detail the extent to which reservations are undermined even in those HEIs that are categorised as Central Universities. Of the 41 Central Universities whose data was submitted, 26 enrolled fewer than 15% SC students, while 23 enrolled fewer than 7.5% ST students. 12 Central Universities enrolled fewer than 27% of students from OBC households as on the same date.

The NIRF and the rankings it produces as such do not account for inclusivity and accessibility in campus spaces. It instead makes a mockery of trying to account for “inclusivity” by considering “the percentage of UG or PG students being provided full tuition fee reimbursement by the institution” as a proxy for the same. Far from being an innocent exercise in convenience, this is to be seen as an insidious attempt to invisibilise a history of marginalisation faced by SC, ST, and OBC communities through the equation of historically grounded social deprivation with material poverty. Despite being entrenched in a culture of discrimination under the guise of meritocracy, elite Indian HEIs thus continue to be recognised and hailed, without any acknowledgement of the need to make them more socially just and accessible spaces.

The NIRF would have thus done well to have accounted for and rewarded in the rankings aspects such as functioning Equal Opportunity Offices in HEIs, minimising dropout rates for SC, ST, and OBC students, efforts to reduce information asymmetry faced by students from marginalised communities to ensure access to jobs and further education, ensuring that reservation provisions are met, and increasing the representation of faculty from marginalised communities, among others. Additional measures including functioning Gender Sensitisation Committee Against Sexual Harassment (GSCASH), facilities including counselling to ensure the mental well-being of students, and the timely disbursement of scholarships to students from marginalised communities need to also be considered and accounted for by any framework that purportedly seeks to serve as a benchmark for Indian HEIs.

The author is a PhD candidate at the University of Edinburgh. Views expressed are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.