Human Rights and Police Reform: An Important but Neglected Report

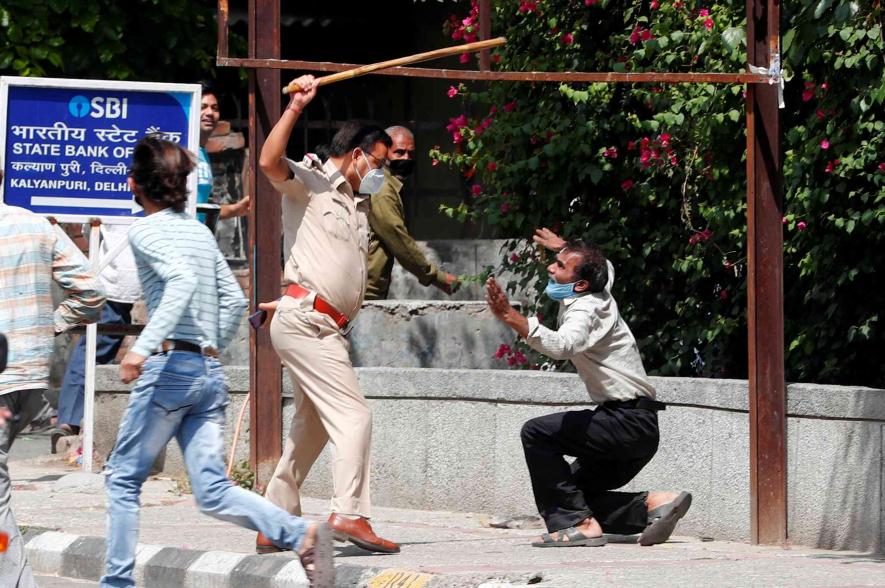

Representational image. | Image Courtesy: Scroll.in

The violence in Northeast Delhi following the February election to the Delhi Assembly witnessed a large number of killings, mostly of Muslims. The victorious Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal of the AAP alleged that about 2,000 antisocial elements from Uttar Pradesh were brought in to carry out the killings since a majority of Muslims of the area had voted for his party rather than the BJP-led Opposition. The role of the police in these events was controversial with massive violations of the human rights of ordinary people. Significantly, the Union Home Minister from the ruling BJP appreciated the law and order management.

On 2 July, eight policemen in Uttar Pradesh were shot dead by the accomplices of a leading criminal in the state. This event has brought into focus linkages between the police, the politicians and criminals. On 19 June, in a different event at Sathankulam in Tamil Nadu, the police gruesomely tortured and killed two innocents accused of a minor offence.

In all these cases and many others in the past, there was a clear structural interaction between police, politicians and the social structure in which the human, legal and social rights of the ordinary people were violated. The role of the police was a key element in the proceedings.

Human Rights Watch Report:

HRW is an important international agency concerned with the protection and promotion of human rights. It calls for far-reaching police and criminal justice reforms. Its reports need serious attention. The important but neglected HRW report, “Broken System: Dysfunction, Abuse and Impunity in the Indian Police, 2009” has made a shattering contribution to the study of the Indian police and criminal justice systems. It brings home to the reader the raw story of the Indian police at the grassroots level, which is ignored in various police reform exercises.

Analysis of the HRW on the Indian Police:

The report finds that the police were overstretched and outmatched in battling India’s pressing problems such as armed militancy, organised crime, and religious and caste violence. The police were found to be poorly trained and had substandard equipment. The public often avoided contact with the police out of fear. Political figures complicated matters by intervening in police operations to protect influential offenders.

Lack of independent investigations into complaints contributed to impunity. Poor working conditions coupled with impunity led to shortcuts to get around systemic impediments. Illegal detention, torture and ill-treatment and failure to punish criminals led to false confessions.

HRW analysed the extensive research on police practices and their human rights record in India. It looked into cases that illustrate the most common human rights abuses by the police. Several victims and witnesses, including torture victims, were interviewed along with interviews of members and lawyers of individuals killed by police in alleged shootouts or deaths in custody. Several interviews were held with individuals against whom police had failed to register cases and conduct investigations. HRW visited police stations in cities and villages. Some officers spent a long time with HRW to provide a better understanding of their daily practices.

Police officers of different ranks were interviewed inside police stations and outside, in the presence of officers of the rank of assistant sub-inspector. Other low-ranking officers were spoken to in the presence of their superiors. Also interviewed were junior-ranking officers who worked as heads of police stations, investigators and assistants to senior police, many of whom spoke on condition of anonymity. Several senior police officers were interviewed along with former police officers, including former members of the National Human Rights Commission. The range of human-interest coverage and documentation carried out by HRW was impressive and exhaustive.

Many issues were discussed such as the nature of abuses; abuses by the police against individuals, usually criminal suspects and the conditions that facilitated and encouraged the police to commit abuses.

The report finds that police misbehaviour was deeply rooted in institutional practices. Government failure to enforce accountability and to overhaul the structure encouraged abusive practices. Several clusters of issues needed attention: police failure to investigate crimes; arrests on false charges and illegal detention; torture and ill-treatment; and extrajudicial killings.

Historically marginalised groups were especially vulnerable to the first three abuses. The vulnerability is a product of an abusive police culture related to an ability to pay a bribe, trade social status or call on political connections; the sources of abuse; disrepair of the police system; political interference and stalled reform; failure to register and investigate cases; illegal arrest, detention and police torture; impunity for extrajudicial killings; obstacles to police accountability.

The danger of a reform agenda that seeks to free the police from political control without making them more accountable to the public became clear from this and many other reports. The Supreme Court’s directions in the Prakash Singh case of 2006 left undisturbed the police’s general immunity from prosecution for serious misconduct, as provided under section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code. Further, any reform agenda must address the working and living conditions of low-ranking police, often the perpetrators of abuses, who carry out illegal orders or operate under a police culture that condones and facilitates such behaviour.

The Supreme Court, while requiring states to establish Police Complaints Authorities to investigate complaints of police misconduct, did not require the police to take preventive measures against human rights abuses. While changing laws to prevent undesirable political influence on police functioning, it was equally necessary to ensure that political control be replaced with accountability of the police to the community.

In noting problematic issues relating to current police reforms efforts in India, especially with regard to section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), HRW is in advance of agencies such as the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), which did not take critical positions with regard to the Supreme Court directions. The report contains several case studies of extrajudicial executions by the police in several states and identifies in its penultimate chapter the obstacles to police accountability in India. After analysing the number of complaints of abuse made and the inquiries made by official agencies, HRW concluded that impunity is still the norm. Police complaints authorities have not been set up in most states and Union Territories. Internal police department inquiries are hampered by the informal code of silence that prevents disclosure of incriminating evidence.

The potential for police intimidation or harassment of individuals complaining of abuse is high because registration of the complaint may require a visit to the very police station where the abuse occurred. A major hindrance to criminal prosecution of police was Section 197 of the CrPC, which requires government approval for prosecution of the police. Several constraints affect the functioning of the national and state human rights commissions that have been set up.

Insights of the author:

• Despite the rhetoric on rule of law, constitutional provisions and the existence of institutions for human rights protection and promotion, the fact remains that at bottom the Indian police remain a government department with hardly any meaningful autonomy.

• The focus on crime and investigation detracts attention from the fact that the existing Indian police organisation is a reproduction of the Irish colonial paramilitary police model with specific characteristics designed to put down political resistance, as noted by David Arnold in his book, Police Power and Colonial Rule, Madras 1859-1947, published by OUP in 1986.

• The provisions of the Indian Penal Code, the CrPC and the Police Act, 1861, all designed during the colonial period focus on security of the state, maintenance of public order and collection of political intelligence bearing on state security rather than on human security and service provision.

• The sample size of the HRW report is small considering India is a large country with 28 states and eight Union Territories.

• The issues of decentralising and democratising the police coupled with empowering Panchayati Raj Institutions to oversee police functions need to be addressed.

• The sufferings of large sections of ordinary people including women and children in the conflict-affected areas of Jammu and Kashmir, the Northeast states and the Central Tribal Belt under the adverse impact of repressive laws affecting human dignity needs to be addressed.

• Intelligence systems oriented to security of state and public order, neglecting human rights concerns need to be addressed.

• The division of the police organisation into three separate wings dealing with investigation, law and order, and local police as recommended in the Second Administrative Reforms Commission report on Public Order (SARC, June 2007) needs attention.

• The role of all-India services such as the IAS and the IPS in law and order management needs review.

-

Institutionalised impunity and lack of accountability for human rights violations by the police have become major issues in Indian politics (The Little Magazine, Impunity: Getting Away with Murder, Part I: Essays, 2010). From Telangana to the villages in Punjab, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu to Jammu and Kashmir, the Northeast and Gujarat, impunity has emerged as a major part of the police system in dealing with crime as well as political dissent, peaceful, or violent. As the democratic content of governance declines, sanction of impunity to law and order agencies grows. Such impunity has existed and grown in a functioning democracy.

-

A vulgarised caste structure, repressive of backward castes, Scheduled Castes and tribes, has adapted itself to a Western-style liberal democracy to produce a distorted democracy described by KG Kannabiran in his book, The Wages of Impunity: Power, Justice, and Human Rights, as “parliamentary fascism”.

-

A plethora of “special” legislations have been enacted over time: Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA), Unlawful Activities Prevention (Amendment) Act (UAPA), Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Prevention Act (TADA) and the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA). These legislations do not achieve their purpose but are often misused by the security forces, as the Delhi Solidarity Group has noted in 2009.

-

In the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, custodial killings or the summary executions of political dissenters have been a part of the administrative culture and from 1996 to 2001 more than 200 such dissenters were reported killed each year in “fake” encounters, which human rights activist and lawyer K Balagopal defines in Selected Articles, Combat Law, as “the practice of taking into custody and extra-judicially executing an individual, then claiming that the victim had died after initiating a shoot-out with the police”. In Jammu and Kashmir, under the AFSPA, security forces have had impunity in suppressing political dissent. Fake encounter killings in Punjab, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Gujarat, and the Northeast have been frequent.

-

A fact-finding team of the Delhi Solidarity Group found in 2009 that in the tiny northeastern state of Manipur (population 25 lakhs), the local police commandos extrajudicially executed over 260 persons during the first six months of the year on the ground that they were militant underground elements. The number thus killed in 2008 was 300. The state has also witnessed heavy militarisation, with about 60 battalions of state and central military and paramilitary forces (in addition to local civilian police) being deployed to quell the ongoing militancy.

In the light of serious human rights violations observers feel that the survival of rule of law in India depends on successful public action to eliminate impunity for the police forces and to secure the social, economic, and cultural rights for ordinary people (The Little Magazine, Impunity: Getting Away with Murder, Part I: Essays, 2010).

Conclusions:

-

The British colonial rulers devised the Indian police system as a cheaper substitute for the army. The main purpose of the police was to maintain British rule in India. Crime control was only a secondary objective to be achieved through fear of the police. This has been noted by Anandswarup Gupta, in his essay in “Law and Order in a Democratic Society”, edited by SV Rao in the Perspectives in criminology series, 1988.

-

The IPC, CrPC and Indian Evidence Act, 1872, enacted by the British put in place a legal framework that equipped the police for the maintenance of British rule by force. The IPC prioritised offences against the state and maintenance of public order. In it, the consideration of traditional crime started only from section 299 in Chapter XVI. Similarly, the CrPC prioritised maintenance of public order and tranquillity before starting analysis of investigation and detection of crime. The Police Act gave priority to the collection and communication of intelligence affecting “public order”. The prevention and detection of crime is mentioned only from section 23 of this act, which is much shorter than the IPC and CrPC (Gupta, 1988).

-

This regressive structure was retained and strengthened after Independence. The Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), a tiny force in 1947, stood at 246,689 in 2006 according to the Annual Report of the Home Ministry for 2005-06). Several other paramilitary forces exist, and together they number over a million. New legislations have come up but in all of them the preoccupation with security of the state and public order has continued while crime control and service to the public take a back-seat.

-

The IPC prioritised offences against the state and maintenance of public order. In it, the consideration of traditional crime started only from section 299 in Chapter XVI. Similarly, the CrPC prioritised maintenance of public order and tranquillity before starting analysis of investigation and detection of crime. The Police Act gave priority to the collection and communication of intelligence affecting public order. The prevention and detection of crime is mentioned only from section 23 of this act, which is, as Gupta notes, much shorter than the IPC and the CrPC.

The author is former Director-General of the State Institute of Public Administration and Rural Development, Government of Tripura. The views are personal.

From the Archives: Why Police Reforms Are Need of the Hour

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.