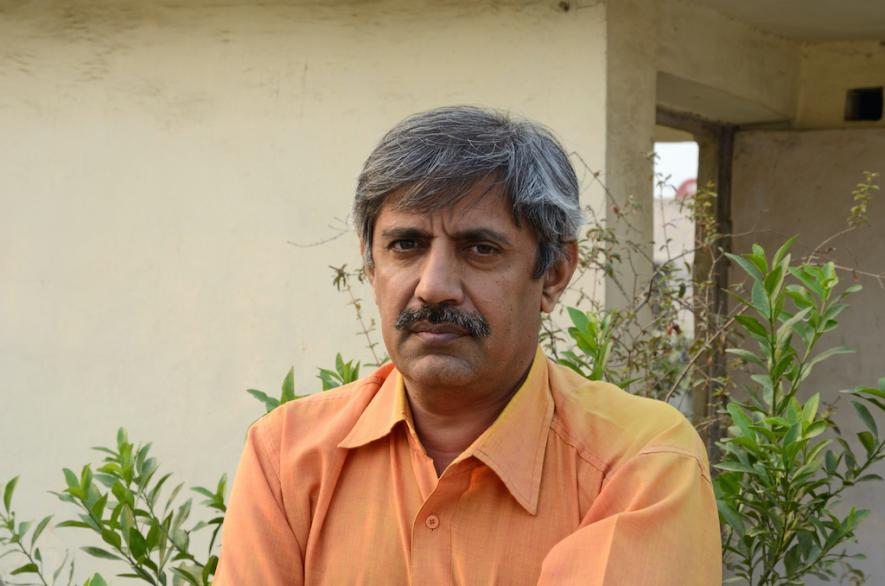

How India Manages Dams is a Sure Prescription for Disaster: Himanshu Thakkar

Barely has the monsoon set in and Assam is already experiencing devastating floods that have left thousands homeless. India has one of the largest networks of dams and yet flooding is an annual event, causing loss of life and tremendous damage to urban centres, villages and agriculture. In this in-depth interview, Himanshu Thakkar, a leading expert on dams and coordinator of the South Asia Network of Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP), an informal network of organisations working in the water sector, spells out steps that must be taken to prevent floods.

The monsoon has just begun but many of our large dams are 70% full already. This seems to be a dangerous situation?

The Central Water Commission under the Ministry of Water Resources monitors the storage situation in 123 of India’s 5,200 dams and brings out a weekly status report every Thursday. If we look at these bulletins closely we find that even as monsoon is just starting in most parts of India, a large number of big dams in India are already filled to the extent of 30%, 40%, 50%, 60% and some over 70% of their storage capacity.

If we are not able to use this water before the next monsoon, it means this massive investment has not been used to generate benefits for those for whom this storage was created. And that too at a time when vast areas and sections of the population were suffering due to shortage of water. Equally important is that now as the monsoon sets in these dams will fill up fast and cause huge flood disasters in the downstream areas. We have dozens of instances when this has happened in recent years.

Why was this water not utilised earlier?

The dam managers need to respond to this question. But broadly, this is because the downstream infrastructure required to best utilise this stored water has not been fully built, or is not functioning or was not required in the first place. In most cases it means the canal network necessary for utilisation of the water has not been built or is not functional.

But this year we have had good rains in the months of February, March and April?

This is not a valid counter because most of the rainfall we receive is from the Southwest Monsoon and the dams have been constructed to store this water for use after the monsoon. The pre-monsoon rainfall, even if above normal, is not significant enough to add to the storage levels. Significantly, some dams like Bansagar on Sone river or Hasdeo Bango in Chhattisgarh have high water storages almost every year prior to the setting in of the monsoon.

How are dams contributing to flood disaster?

In India, unfortunately, dam operations seem to typically mean filling up the dam as soon as water is available and then releasing everything thereafter. This is a sure prescription for disaster. If the dam releases massive flood waters downstream when the downstream area is already facing heavy rain, the dam ends up contributing to floods in a major way.

The dam manager needs to remember that firstly, the character of flood released from a dam is much more destructive than floods in an undammed river. Secondly, the river downstream from the dam is no longer the same as before the dam came up. A dam operator needs to be mindful of the carrying capacity of the downstream river and whenever they release water that leads to increase in water flow downstream, beyond its carrying capacity, the dam operator is contributing to flood disaster.

Why is the Central Water Commission not monitoring this?

Unfortunately the Central Water Commission functions like a lobby in defence of dam operators. They have a clear conflict of interest since they are the ones who sanction dam safety, they sanction the Reservoir Operation Schedule (ROS) or the Rule Curve showing how to fill up the dam during the monsoon period and they are the ones who forecast floods and advise the dam operators during monsoon. They are the ones who make the policies so obviously they will end up defending their own advice.

The CWC’s defence for the factors that led to a flood include that the rainfall was too heavy or the river meandered too much or that the IMD failed to forecast heavy rainfall. They claim that dam operators should follow ROS, but they never assess even in their flood reports if the dam operators followed the ROS or not.

I can cite the example of the CWC report on the devastating floods in Kerala in 2018 or the equally devastating floods that took place in Maharashtra in August 2019. Even in cases where the CWC monitors and forecasts the inflow and operation of dams, they do not compare if the dam is following the Rule Curve.

It is an unfortunate reality that we do not have independent assessment of dam operations during floods and the CWC track record on this score is pathetic.

If there is a conflict of interest as far as the CWC is concerned, then what is the way out?

The track record of the CWC is extremely poor. We urgently need a complete overhaul in the institutional architecture of our water sector. The CWC needs to be disbanded. Flood forecasting and monitoring should be done by an independent body. The draft of the Dam Safety Bill presently before Parliament will not help, since the CWC continues to be the kingpin in all dam safety recommendations, with no role for independent experts.

What are the key steps to achieve safe operation of dams?

We have been demanding for years that water level, inflow, outflow, dam operation information for our large dams must be placed in the public domain on a daily basis. The names and contact details of the persons in charge of dams, the Rule Curve or ROS for the dam, the Emergency Action Plan, the reservoir manual and all meeting minutes and decisions about these should also be placed in the public domain. This is the first step.

At the end of each monsoon, there should be a report from each dam operator, giving details of how the dam was operated during the monsoon. There should be a management committee for each dam, in which 50% of the members must be independent water experts. Another must is an independent assessment after each flood disaster. All these recommendations must be legally binding so that in case there are violations, they can be challenged in courts of law.

Dam operators are not held responsible even when people die. There is no pegging of responsibility despite the widespread havoc that dams cause. What are your views on this?

Yes, this is absolutely unacceptable. The only way out is to have legally enforceable dam operation rules. There must be an independent enquiry after each such disaster to help fix responsibility.

In Kerala in 2018 I understand that 35 of 54 dams were opened up together?

We at SANDRP were the first to warn about this even before the floods started and were most vocal throughout that flood episode. If proper steps had been taken, the damage could have been mitigated.

Or take the devastating 2006 Surat floods due to release of water from the [upstream] Ukai dam. Even after such a massive disaster, we still do not have an inquiry report from an independent group pinning responsibility on what caused the Surat floods. Or take the example of the floods in Kedarnath in Uttarakhand in June 2013, where the official figures state over 6,000 people died though the unofficial figures say 20,000 died. We still do not have a report as to what caused these flash floods and what steps should be taken to prevent its reoccurrence.

After the disastrous floods in Kerala, the state government there has gone in for several measures. These include proper forecasting by private forecasters and better dam management policies. Why is this not being adopted in other states as well?

The Kerala government has brought in a number of changes. They have put out the Rule Curves in public domain, the names and contact details of the engineers responsible for operation of dams, the emergency action plans and reservoir manuals are in the public domain, and they are also putting up daily information about water storage and inflow-outflow of key dams in the public domain. All this is welcome and should become a legal requirement across the country.

Maharashtra also faced Krishna basin floods way back in 2005-06. They faced terrible floods in 2019 also. Were lessons learnt from this?

The Maharashtra state government had set up the Vadnere Committee to look into the floods of 2005. It made a number of recommendations none of which have been implemented. The same Vadnere Committee was set up to look into the reasons that led to flooding in 2019 and it has once again made a number of recommendations. Let us see what happens to these. Basically delay in discharge from Almatti and lack of coordination of water release between Maharashtra and Karnataka led to water coming back to upstream Krishna which led to floods in several Maharashtra villages and in towns of Sangli and Kolhapur.

Also, to give the technical details, the Almatti dam with FRL of 1704.81 ft/ 519.6 m, has a live storage capacity of 119.26 TMC/ 3.105 BCM. The dam was filled up to 1703.99 ft by 28 July, which means dam was already over 99.5% full even before the end of July. Imagine this when there are almost two months of monsoon to go. Even till 27 July, the outflow from the dam was just 3045 cusecs. This was again in complete violation of the Rule Curve and prudent reservoir management. With water levels rising due to rainfall, the dam operators were left with no option but to start releasing more water, starting from 27,095 cusecs on 28 July to 50,4802 cusecs on 11 August, even depleting the reservoir to 1697.92 ft by 11 August. But that did not help much. The key issue is why was the reservoir full at the end of July knowing that heavy rains had yet to set in. Where would the excess water go except downstream.

In Bihar four years ago, flood waters devastated the capital city of Patna. The Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar gave a public statement demanding decommissioning of the Farakka Barrage. What do you feel?

Yes, the chief minister Nitish Kumar said in 2016 that his state government had to tackle unprecedented floods that year. He was right in questioning the role of Farakka dam. He believed that since the Farakka dam was no longer serving the purpose for which it was constructed, the government needed to consider its decommissioning. However, the Bansagar dam also contributed to the flooding in Bihar that year and this dam was already 63% full that year even before the monsoon had started.

The Damodar River Valley also causes flooding. How can this be averted?

The Damodar Valley dams are some of the oldest constructed in independent India. Successive chief ministers including the current one have repeatedly written to the Centre about the role of Damodar dams in contributing to floods in Bihar and West Bengal. Let me point out that this year also, even before the monsoon has started, the Tenughat dam was 46% full, the Maithon dam was 83% and the Panchet Hill dam was 58% full. Here again the question is where will the excess rain water go if the dam is already full up.

Around the world, dams are being decommissioned so that rivers can go back to their natural flow. Why is that not being considered in India?

This question is best answered by the water resources establishment. Besides the demand for the decommissioning of the Farakka dam, there has been a demand for decommissioning of Mullaperiyar dam in Kerala, which is owned and operated by Tamil Nadu, the Dumbur dam in Tripura, the Loktak hydro project in Manipur and the Maheshwar dam on Narmada. When dams become old, unsafe and uneconomical to handle, their decommissioning has to be considered. In India, dams do not need to get any renewal permissions as is the case in the United States and Europe.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.