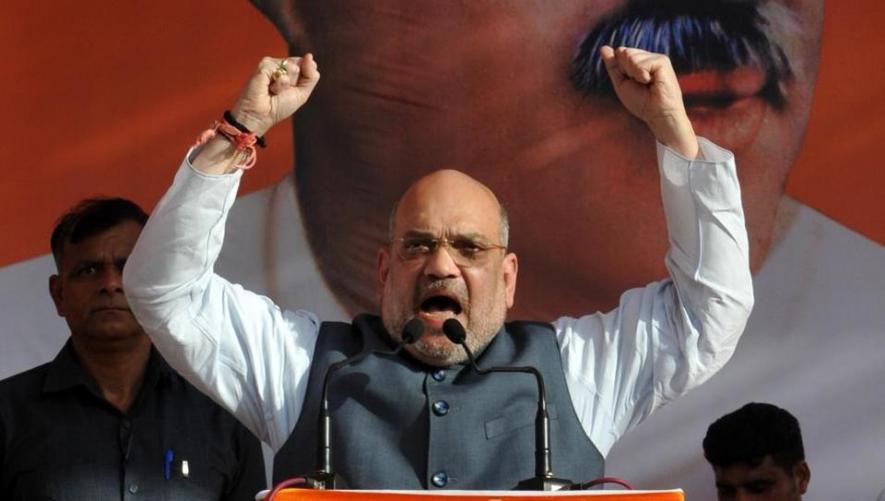

Covid-19: Why No Spotlight is Shining on Home Minister Amit Shah

It is surprising that in an administration and governance model so centralised that only two names pull every lever in it that one of the names, Amit Shah’s, has gone missing. The Union Home Minister has neither been proactively involved in containing the ongoing pandemic nor has he announced any grand plan to be pursued in its wake.

One can easily hazard a guess why Shah had also recently skipped visiting riot-affected areas in Delhi. He had even offered the lame excuse that his going there would have diverted the police to ensuring his security instead of controlling the violence, especially after he had declared that the violence was the result of a well-planned conspiracy.

Only once did Shah give a public statement during the course of the current pandemic. It was to ask state governments to make arrangements for migrants. Beyond this, he seems to be in hibernation. Prime Minister Narendra Modi also shifted the responsibility to look after themselves during this pandemic on to individuals and asked state governments to allot funds to control it. More recently, he issued a notice asking for donations for PM-CARES, a new fund he has set up. He has been making public appearances, and as is his habit, he has converted the crisis into theatrics, making dramatic announcements one day and following up with an apology for the inconvenience it caused the next.

This absence has a model of governance behind it. It either wishes to shift responsibility or attempts to blame and provoke. This is closely linked to the operative logic of the RSS—which is to take credit but not responsibility. It launches monologues dishing out moral sermons, but does not engage in a dialogue of mutuality. Shah, too, does not wish to take responsibility for a crisis that he feels cannot be managed. He does not even feel it is necessary to make an attempt, even if only to fail. Instead, he has preferred to go silent, lest the image of infallibility that he and Modi have carefully cultivated over a period of time gets tarnished.

It is clear that Modi and Shah are in their element when they are provoking, creating narratives, engaging in the theatrics of public oratory and mass hysteria. Beyond this, they are diffident when it comes to handling anything. This very same model was demonstrated by them while handling the economy. They often came across as timid, cluttered and unwilling to learn. This again comes from the training that the RSS offers. It exalts itself as ‘Vishwa Guru’, wherein learning from others is anathema. Under this model, one has to preach without having to learn. One has to dictate without the burden of a shared ethos.

Their shunning all engagement and their habit of dictating terms also allows us a sneak peek into how this model of governance views ‘the people’. To put it simply, the people are seen as dispensable. Cleaning the migrants who had returned to their villages in Uttar Pradesh after the lockdown with sprays of chemical bleach is only a visible demonstration of this cynical imagination. Shah has, in the past, referred to immigrants as “termites”. This stems from a deep disdain for the weak.

The National Security Advisor, Ajit Doval, said without hesitation in a public talk that history remembers the strong and the victors and the vanquished are forgotten. The population is not even seen as target-groups or stakeholders here, but as a dispensable commodity, if they do not fit the models of development and governance. Compassion is seen as a symptom of weakness. Yesterday it was the Rohingyas and Muslims who were the ‘termites’, today it is the migrants. Being dispassionate gives one, it is thought, the advantage of playing ones cards as per the demands of the situation without the limits that law or ethics impose.

Mamata Banerjee is out on the streets, Arvind Kejriwal has made repeated appeals to the migrants to stay back, Kerala has moved to contain the virus at breakneck speed, Telangana has gone for mass testing and quarantining those who have returned from abroad. In a state of humanitarian and health crisis, it is the state governments that are proactive and the Centre that is nearly absent. A Centre that has spoken about cooperative federalism has shifted the financial and administrative burden to the states.

It looks clear that what is going to drive their handling of the pandemic will be the imperatives of their own image. Absence, today, is seen as something that preserves the image of infallibility. But the moot point is how this absence will be received in the popular imagination: it is not a settled issue, as many would imagine. The dynamics of popular politics allows space for different aspects of everyday ethics to overlap and create vastly different narratives. This process is never linear: when Kejriwal resigned as Chief Minister in 2013, he had assumed that people would perceive it as his disinterest in “power politics”, but they chose to view him as irresponsible—someone who is referred to as a ‘bhagoda’ or runaway in popular parlance. When Chandrababu Naidu was ambushed by the Maoists in Tirupati, he called for an early elections imagining a “sympathy wave”, but they defeated him very badly. Which way symbolism flows depends on a complex overlay of factors.

In today’s context, the contest is between the Shah being perceived as incompetent and insensitive for going absent versus the other mode—which the regime is pushing for—his remaining a representative of infallibility. The second option would make the impossibility of finding a solution to a complex socio-economic problem the central issue rather than individual incompetence. We may yet again witness people giving the Modi-Shah duo the benefit of doubt. Images are filtered through cultural systems, and in this context, leader and nation have systematically been converted into home and family. The current dispensation’s mode of governance has invited people to evaluate them as if they were part of their own family. So, one might be unhappy and harbour grave discontent with family members, but one does not go public about it. Instead, one shares the blame and remains prepared for hardships that may follow. The burden of guilt and the gaze has been shifted inwards and that is how Amit Shah expects to escape being in the spotlight.

The author is associate professor, Centre for Political Studies, JNU. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.