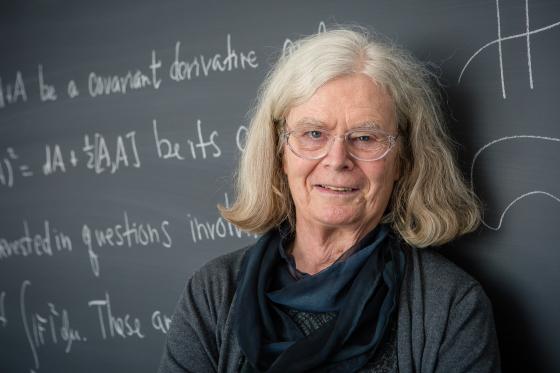

Karen Uhlenbeck First Woman Mathematician to Receive Abel Prize

Image courtesy: Abel Prize. Image for representational purpose only.

Abel Prize, considered as the Nobel in mathematics, has been conferred on Karen Uhlenbeck this year. The Princeton University visiting professor has become the first woman to receive the prestigious mathematics award.

"Her theories have revolutionized our understanding of minimal surfaces, such as those formed by soap bubbles, and more general minimization problems in higher dimensions,” said the statement made by Hans Munthecaas, the Abel committee chairman.

Abel Prize was started in 2002 as an honour to the 19th century Norwegian mathematician Neils Henrik Abel, and is awarded as a recognition and honour to the outstanding scientific work in the field of mathematics, the discipline not included among the Nobel awards.

In her reaction, Uhlenbeck said: “I am a bit overwhelmed. I hope I can hold myself together for this.” She further added, “I am aware of the fact that I am a role model for young women in mathematics. It's hard to be a role model, however, because what you really need to do is show students how imperfect people can be, and still succeed. I may be a wonderful mathematician and famous because of it, but I'm also very human."

With the award, Uhlenbeck has joined the still very small club of women scientists to receive a scientific prize. Out of the 607 Nobel Prizes in physics, chemistry and medicine between 1901 and 2018, there are only 19 women who have been awarded, according to the Nobel Prize website. Marie Curie won the Nobel Prize twice, once for physics and the other time for chemistry. The only woman that received the other Mathematical honor, the field medal, was Maryam Mirzakhani of Iran. She received the field prize in 2014.

Born in Cleveland, Uhlenbeck was not into mathematics in the initial phase of her career. It came only after her enrolment in the freshman honors math course at the University of Michigan. “The structure, elegance and beauty of mathematics struck me immediately and I lost my heart to it,” she wrote in the book Mathematics: An Outer View of the Inner World.

Uhlenbeck attended graduate school at Brandeis University in mid 1960s and chose Richard Palais as her advisor. Palais was exploring the uncharted territory lying between analysis (a generalisation of calculus), topology and geometry (studies the structure of shapes). Uhlenbeck could not resist herself from diving deep into it.

Uhlenbeck, while working as a professor at University of Illinois in mid 70s, was busy in exploring where Palais and his colleague left. But her stay at Illinois was not a happier one—she and her then husband were both professors there and Ulhenbeck was seen mostly as a “faculty wife” there, which irked her much. While in Illinois, she met Jonathan Sacks, a post-doctoral fellow. With him, she studied the mathematical problem—the problem of harmonic map. This led to answer many aspects of the field that remained enigmatic. They could also reveal the “bubbling phenomenon” in mathematics, which later on had been found to exist in physics as well.

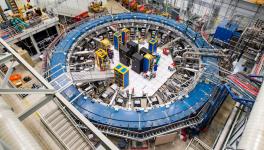

Uhlenbeck’s works with Jonathan Sack was transformative. But it was only in 1980s that her interest in Gauge theory grew, which is an outgrowth of the theory of electromagnetism, and has provided the mathematical foundation for many physical theories, including the Standard Model of Particle Physics. Uhlenbeck discovered many new aspects in this field that could change its entire course.

Also read: Physics Nobel Prize Includes a Woman After 55 Years

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.